Amid the ongoing pandemic and its disastrous effects on multiple aspects of human rights protection across the globe, there is consensus in one area: children and young people have been particularly hard hit. While – thus far at least – they have largely been spared from the direct health effects of COVID‑19, the crisis has had a disproportionate, profound impact on their wellbeing. Virus containment measures have deprived them more than other groups of their usual routines, cutting them off from their social structures and support networks. School closures, lasting many months in some Council of Europe member states, have exposed millions of children not only to reduced learning opportunities but also to isolation, depression and a marked increase in violence and abuse.

In March 2020, UNICEF warned that “all children of all ages and in all countries are being affected in particular by the socioeconomic impacts and, in some cases, by mitigation measures that may inadvertently do more harm than good. This is a universal crisis. And for some children, the impact will be lifelong.” Today, this ominous prediction is considered optimistic by some experts, as two-thirds of children globally are still suffering considerable disruption to their schooling and there are alarming reports of significant growth in mental health needs among children. In addition, economies have contracted while billions are being pumped into recovery programmes, generating budget deficits and debt burdens for years to come – and for our children to address.

While it is sometimes inevitable, especially in a pandemic context and given the pressing need to protect lives, that governments take far-reaching decisions at short notice and without consulting those most impacted, we must honestly acknowledge that such participation gaps are highly problematic.

Policy decisions are made by leaders who are elected by, and accountable to, a population in Europe that is ageing in overall terms. Yet the consequences of many of these decisions will be borne by our children, whether in terms of the learning opportunities they will have, their entry into the labour market or the impacts of future austerity measures on their health and social care services. The disproportionate impact of today’s policies on children and young people has long been acknowledged with respect to climate change and environmental damage in particular. And yet it took the courts to convince European policymakers to take the concerns of young people properly into account and avoid overburdening future generations.

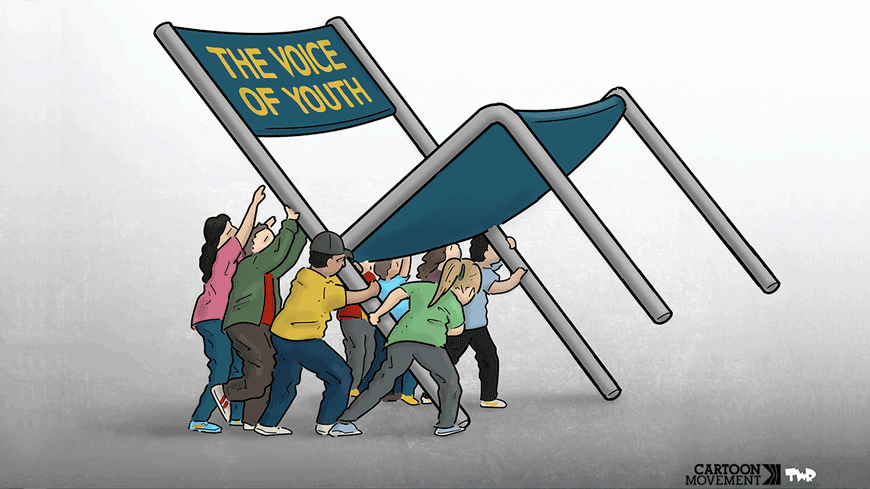

It is therefore high time that we evaluate, self-critically, how successful our efforts have been so far to ensure that children and adolescents have a real chance of being heard and of actually influencing the decision-making processes that impact them. Respecting the right of the child to participate leads not only to better and more effective decisions, it also enriches democracy and helps young people develop citizenship competencies for life.

The right to be heard

According to Article 12 of the 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), ratified by all but one UN member state, “States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.” The Committee on the Rights of the Child has identified child participation as one of the four fundamental and general principles of the Convention, the others being the right to non-discrimination, the right to survival and development and the primary consideration of the child’s best interests. Article 12 thus not only establishes a key right in and of itself but should also be considered in the interpretation of all other rights. The views of children must be taken seriously, and they must be given proper consideration when decisions are made. Article 12 further stresses that participation procedures and mechanisms should widen and become more meaningful as children grow older.

The right to be heard extends to all actions and decisions that affect children’s lives – in the family, in school, in local communities and at national political level. It includes issues relating to transport, housing, macro-economics, the environment, as well as education, childcare or public health. Participation applies both to issues that affect individual children, such as decisions about where they live following their parents’ divorce, and to children collectively and as a group, such as legislation determining the minimum age for full time work.

In its General Comment No. 12 on the right of the child to be heard, the Committee on the Rights of the Child stressed that the implementation of this fundamental right remains elusive in most societies around the world. Measures taken are often not very effective. Longstanding practices or attitudes and political and economic barriers prevent children from expressing their views on matters that affect them and from having these views duly considered. The Committee suggested that real child participation requires the dismantling of all legal, political, economic, social and cultural barriers and, beyond a commitment to invest resources and training, readiness to challenge existing assumptions about children’s capacities.

Today, at a time of unprecedented crisis with decisions profoundly affecting all aspects of children’s lives and set to continue doing so for many years to come, a wide range of welcome efforts are being made to promote child participation across Europe. And yet there is also a growing body of research reflecting on whether the current opportunities for children to influence public decision-making are effective and reasonable from a child’s perspective or whether they are often not merely symbolic. Few governments have made systematic efforts to institutionalise mechanisms at different levels for children to participate actively and meaningfully in all decisions that affect them. In many countries children still face challenges in accessing information about their rights and national policies that affect them.

Defining participation

Participation is widely considered as ‘taking part’ in an activity, process or community, involving responsibility, action and a recognised role in influencing decision-making processes. It is a continuous, systematic process, not a formal structure or single event. Participation requires training and engagement at all levels and, therefore, the provision of adequate resources. Crucially, promoting meaningful and genuine participation calls for an attitude that does not underestimate children’s and adolescents’ views but supports and encourages their right to participate in democratic processes.

Children and adults do not see the world alike. There are countless examples of policies, for instance to reduce child poverty or design child-friendly spaces that were developed by adults with the very purpose of benefiting children but that in fact had negative consequences for children. As we know from other domains, meaningful participation plainly leads to better decisions. Children are not only “adults-in-the-making”, they have unique perspectives that are essential to identifying, addressing and solving issues.

Unless we listen carefully to children and adolescents and involve them in all related processes, we will not therefore be able to create better learning opportunities, abolish discriminatory attitudes in schools or more effectively address violence against children at all levels.

Challenges to participating

It is often argued that children lack the experience and maturity to participate and that they do not understand what is in their best interest. This overlooks the fact that even small children articulate clear preferences, develop nuanced capacities for negotiating their friendships and family relations and have a deep sense of justice and social responsibility. It is also sometimes said that children are easily manipulated and influenced. Yet individuals vary considerably, and many adults are easily influenced, too. In addition, the argument contradicts the concept of evolving capacities inherent in the CRC, which requires recognition of the fact that children in different environments and cultures, and faced with diverse life experiences, acquire competencies at different ages. There is a growing body of evidence, for instance, of the significant contribution that children make in emergency situations, and I welcome the WHO’s recent co-operation project with six large youth organisations on addressing the impact of COVID‑19.

Another challenge to participation involves it being reduced to something rather formal and therefore not genuine or effective. The danger has been highlighted that child participation frequently resembles tokenism and decoration, sometimes even resulting in manipulation, as children may not be clear about their role and actual impact on relevant processes. If children are involved solely for the sake of “window-dressing” but all real decisions are left to adults, if children’s views and wishes are sometimes even used as arguments but without their true needs and interests being taken into account, there is a danger of children becoming frustrated and coming to think that participation leads nowhere. This may lead to cynicism and disengagement.

Effective measures to empower children and adolescents

The Council of Europe has devoted significant efforts to boosting effective child participation. Recommendation CM/Rec(2012)2 on the participation of children and young people under the age of 18 sets out general principles and calls on member states to protect children’s right to participate through legal, financial and practical measures, to raise awareness and training opportunities regarding participation and to create spaces for participation in all spheres.

Efforts to promote child and youth participation can be categorised into three different types of processes: consultative, collaborative and those promoting self-advocacy. When identifying the most appropriate method, it must be borne in mind that the first two types are usually adult-initiated and that special efforts must be made to ensure that children are offered a real chance of influencing both the agenda-setting process and also the choice of methodology used.

As general principles of effective child participation, it is important that children be involved from the earliest possible stage onwards and that the rules of the process, including about the decisions that can be made and by whom, are transparent to them. Children are not a homogenous group. As with society as a whole, the views and perceptions of the more disadvantaged and marginalised, including children with disabilities and from minority backgrounds, may need to be sought out proactively so that they are taken properly into account. All participation should be voluntary. The mechanism should be age-appropriate and chosen in accordance with the evolving capabilities of children, treating them all with equal respect regardless of their age, ability, situation or other factors.

Child participation should build the self-esteem of children and empower them to identify and tackle abuse or neglect of their rights. When successful, it should help children develop active citizenship competencies. It is crucial therefore to provide feedback to children on how their input was used and how it influenced any decisions that were taken. Lastly, children’s involvement is vital when it comes to evaluating the participation processes and assessing the quality of participation.

Promising practices

Various encouraging initiatives do thankfully exist to ensure that children are offered a meaningful opportunity to participate.

In Serbia in 2020, over 1 500 children took part in an anonymous online consultation about how the COVID crisis had affected them. Their concerns were fed into advocacy work and policy papers at national and European levels. Save the Children set up mobile teams to work with refugee and migrant children between countries and in transit centres in the Western Balkans so as to provide them with information and seek their views regarding child protection case management. Consultations with children also inform programme design, monitoring and evaluation, reflecting the crucial nature of child-friendly information and proper participation in situations where children are most vulnerable.

Examples of successful collaborative processes include, for instance, the active involvement of children in the General Discussions organised by the Committee on the Rights of the Child. Children make submissions on the discussion themes, participate in the design and planning of the day, act as session co-chairs and actively take part in all discussions. Eurochild’s Strategic Plan 2019-20 was drawn up jointly with children in a collaborative process during which children influenced activities, campaigns and strategic planning events, and continue to be involved in policy development through monitoring and evaluation. In Italy, Milan City Council involved the city’s children in planning, transforming and co-managing the renewal of nine school gardens.

The Scottish Youth Parliament is a prominent example of a child-led structure which has inspired other such initiatives. Officially launched in 1999, it was established as a follow-up to the review of how Scottish democracy could work and the realisation that young people and children should play an active role in it. Policies are developed by elected representatives and directly fed into the Scottish Parliament. There are also annual cabinet meetings where representatives of the Youth Parliament have an opportunity to speak to senior politicians about the issues that affect them most.

These are important tools to ensure that the voices of children count and have a direct impact. As such, they are also key in building the trust of young people in political processes and institutions. According to an OECD study, young people’s trust in public institutions and their perception of having political influence and representation in decision-making have stalled. At the same time, children and adolescents demonstrate strong motivation for addressing global challenges such as climate change, rising inequality, shrinking space for civil society and threats to democratic institutions. Fridays for Future is a case in point.

Promoting democratic participation

In some Council of Europe member states, the voting age has been lowered in an effort to address barriers to youth participation in political life, ensure more age diversity in public consultations and obtain more inclusive policy outcomes. Austria lowered the general voting age to 16 as long ago as 2007, Greece lowered it to 17 in 2016 and in Malta, 16-year-olds have been able to vote since 2018. In several other countries (such as Estonia, 12 Länder in Germany, as well as Scotland and Wales) the voting age has been lowered to 16 for local and regional elections. Experiences overall are highly positive, suggesting that 16‑year-olds prepare themselves well and vote very similarly to 18-24‑year-olds. There has been no evidence of a tendency among young people to vote for more radical or ‘bogus’ political parties. Lowering the voting age is also believed to be an effective tool to generate interest and greater awareness of politics at an earlier age, leading to more political involvement and higher voter turnout later in life. In fact, turnout among 16-17-year-old voters has been shown to be slightly higher than that of 18-24-year-olds. This is linked to the generally more stable life situation at that age, careful preparation at school and the fact that engagement with politics is still viewed as meaningful and positive rather than a senseless and frustrating experience.

States enjoy a wide margin of appreciation in establishing age restrictions for the right to vote – as long as the criteria are reasonable and proportionate. According to the Venice Commission, the right to vote must be conferred at the age of majority at the latest. The highest age limit that Council of Europe member states may set is therefore 18, but they can go lower based on their own assessment. Article 12 of the CRC obliges states parties to give weight to the views of the child “in accordance with their age and maturity”. It therefore makes sense to give effect to the increased political awareness of today’s young people, which is due, among other things, to greater access to information.

The voting age has been lowered continuously over past decades to expand the recognition of citizen authority as a basic principle of representative democracy. With few exceptions, population ageing has decreased the share of young voters across Council of Europe member states and concerns about fairness and solidarity between generations are being raised increasingly frequently in public policy debates. Lowering the voting age facilitates intergenerational discourse in parliaments and helps place youth issues on the political agenda – even though older voters will still greatly outnumber younger ones for many years to come. While lowering the voting age is not the only effective means of boosting youth participation, it is certainly a powerful message to our children that we stand ready to listen to them, take their views seriously and give them a choice.

From having a voice to having a choice

Young people have proven that they are interested and well informed, with growing political responsiveness and a clear sense of wanting to participate in decision-making processes. It is time to move away from symbolic approaches to child participation. Today’s children will bear the consequences of today’s decisions, whether regarding the environment, health policies, economic recovery or pension funds. Let’s seize the current opportunity of reflection and ‘building back better’ to show courage, foresight and strong commitment to Article 12 of the CRC. Let’s give children a voice through open and inclusive consultations and collaborate closely with them when setting agendas and priorities and when designing, implementing and evaluating policies that affect them. Let’s proactively encourage and support child-led initiatives that aim to improve existing patterns, empowering young people to make choices and meaningfully influence their future. And lastly, let’s promote their effective democratic participation, including by giving serious consideration to lowering the voting age.

Dunja Mijatović

Useful references:

- Recommendation CM/Rec(2012)2 of the Committee of Ministers to member States on the participation of children and young people under the age of 18, adopted in March 2012

- Council of Europe Child Participation Assessment Tool “Indicators for measuring progress in promoting the right of children and young people under the age of 18 to participate in matters of concern to them”, March 2016

- Participation implementation and promotion activities of the Council of Europe Children’s Rights Division

- Participation activities of the Council of Europe Youth Policy Sector

- Youth participation activities of the Council of Europe Congress of Local and Regional Authorities

- General Comment No. 12 ‘The right of the child to be heard’, CRC/C/GC/12, adopted by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child on 20 July 2009

- UNICEF Innocenti Working Paper on Transformative Change for Children and Youth in the context of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, February 2019

- Save the Children Live Tracker on child participation during COVID-19