Early warning, rapid response, protection

Early-warning, rapid response mechanisms and protection measures to ensure the safety of journalists (paragraphs 8 – 10 of the Guidelines)

Legislation criminalising violence against journalists should be backed up by law enforcement machinery and redress mechanisms for victims (and their families) that are effective in practice. Clear and adequate provision should be made for effective injunctive and precautionary forms of interim protection for those who face threats of violence.

State authorities have a duty to prevent or suppress offences against individuals when they know, or should have known, of the existence of a real and immediate risk to the life or physical integrity of these individuals from the criminal acts of a third party and to take measures within the scope of their powers which, judged reasonably, might be expected to avoid that risk. To achieve this, member States should take appropriate preventive operational measures, such as providing police protection, especially when it is requested by journalists or other media actors, or voluntary evacuation to a safe place. Those measures should be effective and timely and should be designed with consideration for gender-specific dangers faced by female journalists and other female media actors.

Member States should encourage the establishment of, and support the operation of, early-warning and rapid-response mechanisms, such as hotlines, online platforms or 24-hour emergency contact points, by media organisations or civil society, to ensure that journalists and other media actors have immediate access to protective measures when they are threatened. If established and run by the State, such mechanisms should be subject to meaningful civil society oversight and guarantee protection for whistle-blowers and sources who wish to remain anonymous. Member States are urged to wholeheartedly support and co-operate with the Council of Europe’s platform to promote the protection of journalism and the safety of journalists and thereby help to strengthen the capacity of Council of Europe bodies to warn of and respond effectively to threats and violence against journalists and other media actors.

Indicators

Indicators

|

Risks |

Measures to avert/remedy the risks |

|

Threats of violence

|

|

|

Real and immediate risk to the life or physical integrity of journalists, whistle-blowers and other media actors |

Reference texts and other relevant sources

Reference texts and other relevant sources

Statistics

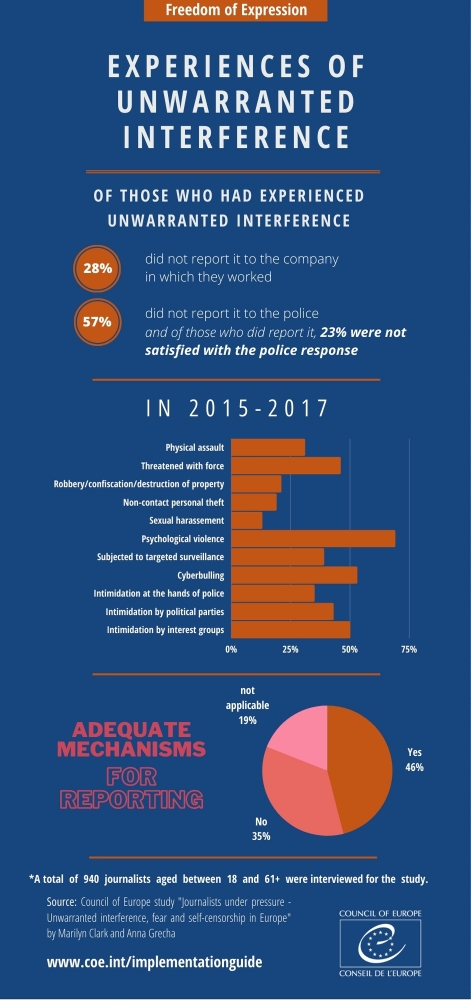

The Study “Journalists under pressure” highlights that out of 1,000 journalists and other news providers questioned for the study, over a third believe that there are no effective means by which they can report threats. Of those who had experienced unwarranted threats and interference,[1] 57% did not report it to the police and of those who did report it, 23% were not satisfied with the police’s response.[2] Not being aware of any mechanisms in place was the main reason cited by journalists for not reporting experiences of unwarranted interference. Such lack of awareness was compounded by the fact that journalists lacked trust in the mechanisms that did exist and feared retaliation as a result. A lack of trust in the mechanisms was in some cases also due to unsuccessful attempts at reporting unwarranted interference in the past.[3]

[1] The study defines unwarranted interference as “acts and or threats to a journalist’s physical and/or moral integrity that interfere with journalistic activities … [that] may take the form of actual violence or any form of undue pressure (physical, psychological, economic or legal) and may emanate from state or public officials, other powerful figures, advertisers, owners, editors or others”.

[2] Study “Journalists Under Pressure - Unwarranted interference, fear and self-censorship in Europe”, Marilyn Clark and Anna Grech, 2017, Council of Europe, page 9.

[3] Study “Journalists Under Pressure - Unwarranted interference, fear and self-censorship in Europe”, Marilyn Clark and Anna Grech, 2017, Council of Europe, page 37.

Interim protection

The objective of injunctive/precautionary forms of interim protection is to offer a fast legal remedy to protect journalists and other media actors from acts of violence, prohibiting, restraining or prescribing certain behaviour of the perpetrator. Taking inspiration from Article 53 of the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (the Istanbul Convention), for an injunctive and precautionary form of interim protection to be effective, it should offer immediate protection and be available without lengthy court proceedings or undue financial or administrative burdens on the victim. Furthermore, these orders should be issued on an ex parte basis with immediate effect and should be available irrespective of, or in addition to, other legal proceedings. Finally, effective, proportionate and dissuasive sanctions should be foreseen for any breach of such orders.

Early warning/rapid response mechanisms

Hotlines (direct 24/7 telephone lines) are among the most common forms of early warning /rapid response mechanism that enables immediate, secure communication in cases of emergency.

Cooperation with the Council of Europe Platform

The Council of Europe’s Platform to Promote the Protection of Journalism and the Safety of Journalists is another early warning/rapid response mechanism, as well as a tool for enhancing the response capacity of Council of Europe bodies and for improving co-operation and co-ordination with other international organisations. The Platform allows its contributing partners (civil society and journalist associations) to post alerts, subject to their own verification processes and standards. When the circumstances permit, the Council of Europe and a member state which is directly referred to in information posted on the Platform, may post reports on action taken by their respective organs and institutions in response to that information. The Platform also helps the Council of Europe to identify trends and propose adequate policy responses in the field of media freedom.

Protection of life from real and immediate risk

Journalists and other media actors whose lives or physical integrity are at a real and immediate risk should have immediate access to law enforcement authorities (hereinafter - LEAs) and/or to a special protection/safety mechanisms.

Effective and timely police protection

Article 2 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (the Convention) protects the right to life and encompasses, inter alia, a positive obligation of the authorities to take steps to preserve life in case of an imminent risk. This positive obligation means that the state must take preventive operational measures to protect the life of individuals within its jurisdiction, when it knows or ought to have known that there is a real and immediate risk to the life of an individual or individuals due the criminal acts of a third party.

In assessing the authorities’ knowledge of any such risk to life, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR, the Court) may take into account the extent to which bodies of the state such as prosecutors should have been aware of the vulnerable position which journalists are in vis-à-vis those in power (e.g., because of the elevated number of deaths or bodily injuries suffered by journalists in that country). In Dink v Turkey, for instance, the Court found that the security forces could be considered to have been informed of the intense hostility towards Mr Dink from extreme nationalists as a result of his newspaper articles on Turkish-Armenian relations and of a real and imminent threat of his assassination, but have failed to take reasonable measures to protect his life.[1] Accordingly, it found a violation of Articles 2 and 10 of the Convention.

Appropriate preventive operational measures would thus encompass an individual risk assessment to identify specific protection needs, police protection and/or voluntary evacuation to a safe place. Protection programmes run by the police should go hand-in-hand with a speedy investigation of the threats received/acts of violence perpetrated. They should be conceived as temporary measures to ensure journalists’ and other media actors’ physical safety during the time needed to bring the perpetrators to justice by court proceedings.

In line with Principle 17 of Recommendation CM/Rec(2016)4, systematic, gender-sensitive approach is required also in relation to preventive operational measures to prevent and combat these specific dangers, such as gender-based threats, (sexual) aggression and violence. In this connection, Article 19 of the Istanbul Convention requires that victims be provided with information on the different types of support services and legal measures available in cases of violence against women. This includes information on where to get what type of help, and in a timely manner, meaning at a time when it is useful for the victims.

Relocation, safe houses or shelter

Journalists’ organisations and other NGOs have developed a range of schemes for relocation of journalists and other media actors and their family members facing real and immediate risk to shelters and other safe locations. Mostly funded by journalists for journalists, these schemes importantly complement protection measures offered by state.

Comprehensive national protection mechanisms

As concerns the set-up of a specialised safety/protection mechanism for journalists and other media actors, it has been found, by and large, that the problem of attacks or threats needs to reach a certain degree of seriousness before this can be effective.[2] The worsening of the environment in many Council of Europe member states, as exemplified by the staggering increase of killings and violence registered on the Platform, would warrant that many member states consider the possibility of establishing such mechanism.

[1] Report on “The principles which can be drawn from the case-law of the European Court of Human Rights relating to the protection and safety of journalists and journalism”, Philip Leach, page 11.

[2] Discussion Paper “Supporting Freedom of Expression: A practical Guide to Developing Specialised Safety Mechanisms”, April 2016, UNESCO and Centre for Law and Democracy, Toby Mendel, page 20.

Valuable practices and initiatives which provide guidance in this area

Valuable practices and initiatives which provide guidance in this area

Early warning/rapid response mechanisms

- The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) hotline for journalists on dangerous assignments,[1] the Press SOS hotline of Reporters Without Borders (RSF)[2] and the press freedom hotline of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)[3] are among time-tested early warning/rapid response mechanisms.

- The European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF), in partnership with the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ), created in March 2016 an Alarm Centre for Female Journalists Under Threat.[4]

- In the Netherlands, a hotline enabling journalists to report acts of aggression and violence has been set up.

- In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Free Media Helpline is run under the auspices of the BH Journalists Association.[5]

- In Sweden, under the national Action Plan on Defending free speech,[6] a national helpline and local victim support centres for individuals who are exposed to threats and hatred in connection with their participation in public debate are being set up.

- In Armenia, the Committee to Protect Freedom of Expression has set up a 24/7 hotline to report cases of violence against journalists. When calls are received, a fast response group goes on the site of the incident, assesses the situation and takes necessary measures.

- In Pakistan, Worth cyber-harassment helpline for journalists has been launched, which aims to provide legal advice, digital security support, psychological counselling and a referral system to victims.

- In Western Balkans countries, the Regional Platform for advocating media freedom and journalists’ safety (a network of journalist associations and media trade unions) has established a regional System of Early Warning and Prevention (SEWP), which also includes an Online Platform for Immediate Reporting of Attacks on Journalists and Violation of their Rights.[7]

- In Tunisia, with the technical and financial support of the UN OHCHR and UNESCO, a Monitoring Unit within the Syndicat National des Journalists was established in 2017. It aims to: provide journalist victims with legal advice and assistance; engage the national human rights institutions (NHRIs) and inform the OHCHR in case of serious violations; develop a national database on violations of journalists’ safety; prepare and publish monthly reports on the safety of journalists; develop safety of journalists’ indicators.[8]

Cooperation with the Council of Europe Platform

- In France, inter-ministerial informal coordination has been organised to speedily deal with Platform alerts. The Permanent Representation of France to the Council of Europe transmits an alert to the Ministry for European and International affairs (MEAE), which identifies the Ministry competent to deal with it. Within each Ministry, a focal point is designated to respond to such alerts. Within a short delay upon receipt, the focal point transmits the response to the alert back to the MEAE, which in its turn transmits it to the Permanent Representation to the Council of Europe, and then to the Platform.

[1] The ICRC has a 24-hour hotline that may be used when a journalist on assignment disappears, is captured, arrested or detained. It operates in the areas where the ICRC conducts humanitarian activities. The ICRC may be alerted by the journalist’s family, editor, national press organisation or a regional/international press association. Its recognised role as a neutral intermediary enables it to carry out a range of operations, including obtaining information, passing information to the family, requesting permission to visit the journalists (accompanied by a doctor) and repatriating the journalist.

[2] Reporters Without Borders maintain a 24/7 press SOS hotline in cooperation with American Express. The hotline can be alerted by journalists in trouble, their families, employers or professional organisations. An RSF representative will provide the journalist with advice or relevant contacts or will alert local or consular authorities.

[3] The CPJ provides a secured on-line platform on which journalists and other media actors can report press freedom violations, including threats/attacks. It also provides help for journalists under threat, including links to resources available through other organisations which provide emergency relocation, legal, prison family, medical and trauma support.

[4] The Alarm Centre for Female Journalists Under Threat acts as a reporting point or hotline for female journalists who have been the target of gender-based threats, such as sexual and abusive comments, threats of rape or publishing pictures and phone numbers on sex and dating websites. The Alarm Centre allows for confidential, encrypted communication handled exclusively by female staff at the ECPMF who offer solidarity and legal assistance and also work to make the dimension of gender-based attacks more visible.

[5] Discussion Paper “Supporting Freedom of Expression: A practical Guide to Developing Specialised Safety Mechanisms”, April 2016, UNESCO and Centre for Law and Democracy, Toby Mendel, page 20.

[6] The full title is: Swedish Action Plan on Defending free speech – measures to protect journalists, elected representatives and artists from exposure to threats and hatred.

[7] The SEWP aims to: advocate freedom of expression and integration of EU media freedom standards; prevent violence against journalists and abuses of freedom of expression; introduce a methodology for continuous monitoring of media freedom and journalists’ safety and the public availability of information on human rights violations of journalists, editors and other media professionals. Its Online Platform for Immediate Reporting of Attacks on Journalists and Violation of their Rights enables the reporting of attacks and provides support to journalists. It also contains a database on attacks on journalists since 2014, as well as data on public actions, analyses, advocacy activities of its partners and other media organisations.

Protection of life from real and immediate risk

Effective and timely provision of police protection

- British LEAs have responded to the Court’s judgment Osman v. the UK[1] by putting in place a procedure for thorough risk assessment that must be carried out if an initial assessment of a report points to the existence of a real and immediate threat to a victim.[2]

- In Italy, within the Ministry of Interior, a Central Bureau of Inter-Forces for Personal Security (UCIS) has been created to ensure that appropriate measures are implemented to secure protection to those who are exposed to potential or actual danger due to their profession or for other reasons (including journalists and other media actors investigating organised crime who face threats of violence).[3]

- EU Directive 2012/29 on “Establishing minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime” provides under its Article 22 for a procedure for assessment of individual risk and identifying special protection needs.[4]

- In Sweden, the police authority's crime victim and personal security division (BOPS), which is responsible for providing support to victims, maintains contact with those responsible for security at media houses in the respective regions. BOPS can offer personal protection to those who are threatened and collaborates with other parts of the police when victim support or personal protection is needed. When a democracy violation is reported, the police meets with the person who has made the report. If the threat is considered to be serious, police protection may be provided.

Schemes providing for relocation, safe houses or shelter

- The IFJ’s International Safety Fund (set up in 1992), funded by journalists for journalists, provides timely financial assistance for, among others, emergency travel and accommodation to journalists and their family members at risk.

- The IFJ provides safe houses in the West and some parts of East Africa and Latin America. IFJ's safe houses are run by reliable members/affiliates which are not informed of the identity of the person staying in the safe house and the persons at risk can stay for a period from three to six months.

- In Sweden, in 2010 and 2011 the FOJO Media Institute opened a safe house to give shelter to journalists who are under severe and acute threat related to their profession. Journalists can stay there for a limited three-month period.[5]

- The International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) is an independent organisation of cities and regions offering shelter to those at imminent risk of persecution/under threat as a direct consequence of their creative activities, including journalists. ICORN member cities: arrange for the relocation to / reception in the city; facilitate the acquisition of a legal status; provide the person at risk and his/her family with an appropriate dwelling; provide an appropriate scholarship/grant for his/her period of stay; help with integration in the local community, both socially and artistically; appoint a City of Refuge coordinator to provide support with legal and practical matters.

- The ECPMF provides journalists who are in danger with temporary accommodation and an allowance for their needs.

Comprehensive national protection mechanisms

- Colombia’s Protection Programme for Journalists and Social Communicators established in 2000, notwithstanding some flaws, has been identified by many as representing a best practice example for protection mechanisms. Its key actor is the National Unit for Protection (UNP), which implements and monitors the physical measures of protection.[6]

- Once the UNP receives a complaint directly from the journalist or through civil society/LEAs, it receives input from three basic structures:

- The Technical Corps for Information Collecting and Analysis (CTRAI) - an inter–institutional group consisting of members of the UNP and the national police. CTRAI verifies the information it receives and uses a “risk assessment matrix” (weighing threat, risk and vulnerability) to determine a risk assessment score for the journalist;

- The Preliminary Assessment Group - which reviews information from CTRAI on individual cases, establishes the level of risk and makes recommendations; and

- The Committee for Risk Assessment and Recommendation of Measures (CERREM) - decides on the allocation of protection measures (including the provision of mobile phones, bulletproof vehicles, emergency evacuation and transfers). Civil society can object to the measures.[7]

- In Italy, within the Ministry of Interior, a Coordination centre on the monitoring, analysis and permanent exchange of information on the intimidation of journalists was set up in 2017. In addition to the Minister of Interior who chairs this body, the Coordination Centre includes the head of the police, a high representative of public security, the Secretary General and the President of the National Federation of the Italian Press and high representatives of the national journalist association, with the possible participation of other experts and representatives of civil society.

The Coordination centre aims to formulate proposals/strategies on how to prevent and counteract intimidation and violence against journalists, including by adopting specific protection measures. The Centre has set up a dedicated Secretariat with operational capacity, serving as the main gateway between journalists and law enforcement/public security officials. It monitors and analyses data provided by the prefects and the local units of the police on attacks and intimidation of journalists and identifies preventive strategies and specific protective measures to the Coordination Centre. The Coordination centre has decided to convene meetings every trimester.

- In Mexico, a Federal Protection Mechanism of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists has been set up and a position of a Special Prosecutor for Crimes against Freedom of Expression (FEADLE) has been created. The protection programme provides journalists and activists deemed to be at risk with safe houses, police protection, or a panic button to call for help. However, it lacks funding and personnel to respond in a timely and effective manner to the urgent requests it receives.[8]

- In Nepal, a new mechanism is under development to address the need for protection and to combat impunity. The Nepal’s National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), an independent and autonomous constitutional body with a mandate to investigate human rights abuses, will administer the mechanism. Representatives of the Federation of Nepalese Journalists, the Nepal Bar Association and the NGOs Federation will be part of the system, including participation in its oversight committee and response teams. The mechanism is intended to implement both proactive and reactive measures to prevent attacks and violence against those exercising their right to free expression and to ensure the prosecution of suspects and justice for the victims.[9

[1] Osman v. the United Kingdom (GC), no. 23452/94, 28 October 1998.

[2] The full risk assessment process comprises: receipt of the threat report by the police; provision of information to the victim; assessment of the nature and severity of the threat (including an initial investigation and classification); response to mitigate the threat/risk including devising and initiating a strategy for preventative or disruptive measures; resolution – initiating the agreed strategy leading to the removal or reduction of the threat/risk; monitoring - maintaining an overview of the developing intelligence picture and reassessing the risk management measures.

[3] When journalists or other media actors’ lives or physical integrity are at immediate risk, UCIS, together with the prefect, carries out an individual risk-assessment in order to identify specific protection needs of the victim. Four different levels of protection exist, depending on the risk level: “extraordinary” (1st), “very high” (2nd), “high” (3rd) and “low” (4th). Protection measures can consist in domicile supervision, dynamic vigilance, voluntary evacuation to safe places, police guards escort with armoured cars, etc. Personal security of those under protection is constantly monitored and a new assessment is issued every six months, in order to confirm the protection level and the need for the protection measures, or to modify and eventually revoke them.

[4] According to Article 22 of the EU Directive 2012/29 on “Establishing minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime”, “Member States shall ensure that victims receive a timely and individual assessment (…) to identify specific protection needs and to determine whether and to what extent they would benefit from special measures in the course of criminal proceedings, due to their particular vulnerability to secondary and repeat victimisation, to intimidation and to retaliation. The individual assessment shall, in particular, take into account: (a) the personal characteristics of the victim; (b) the type or nature of the crime; and (c) the circumstances of the crime”. The individual assessment must pay particular attention to victims who have suffered considerable harm due to the severity of the crime (including gender-based violence) and victims who have suffered a crime committed with a bias or discriminatory motive which could be related to their personal characteristics.

[5] CDMSI Workshop on “How to protect journalists and other media actors in Europe: implementing the Council of Europe’s standards”, Strasbourg, 30 June 2016, Compilation of Selected Best Practices for the Implementation of Recommendation CM/REC(2016)4 and Proposals for Further Follow-up Activities, by Patrick Leerssen, Roel Maalderink and Tarlach McGonagle, page 8.

[6] Some of Colombia’s Protection Programme for Journalists and Social Communicators successful attributes include: civil society and media participation in the mechanism (they refer cases and are closely involved in the risk assessment process); structures of coordination between state institutions, journalists and civil society organisations; independence, including a dedicated budget; taking gender into account, offering specialised assessments for women and by women if necessary; support by a legal framework, public policy and court jurisprudence.

[7] See “Defending Journalism: How National Mechanisms Can Protect Journalists and Address the Issue of Impunity - A comparative analysis of practices in seven countries”, International Media Support, 2017, pp.104 – 105.

[8] “Defending Journalism: How national mechanisms can protect journalists and address the issue of Impunity, a comparative analysis of practices in seven countries”, International Media Support, 2017, page 39.

[9] CDMSI Workshop on “How to protect journalists and other media actors in Europe: implementing the Council of Europe’s standards”, Strasbourg, 30 June 2016, Compilation of Selected Best Practices for the Implementation of Recommendation CM/REC(2016)4 and Proposals for Further Follow-up Activities, by Patrick Leerssen, Roel Maalderink and Tarlach McGonagle, page 41.

Other measures

- In Sweden, in the context of the Action Plan on “Defending free speech – measures to protect journalists, elected representatives and artists from exposure to threats and hatred”[1] the Government has:

- Commissioned the Swedish Crime Victim Compensation and Support Authority to produce a training and information resource on support for journalists (as well as politicians and artists) who are exposed to threats and hatred. The resource is intended for government agencies and organisations that need better tools to support these categories of victims, but also for private individuals who are exposed to threats and hatred in the public debate.

- Commissioned Linnæus University to build a knowledge centre and a service offering advice and support to journalists and editorial offices, including freelancers, small offices and smaller production companies.

[1] For further details please see: Swedish Action Plan on Defending free speech – measures to protect journalists, elected representatives and artists from exposure to threats and hatred.

Suggestions for implementation

Suggestions for implementation

Interim protection

- Ensure that injunctive/precautionary forms of interim protection provide a fast legal remedy to protect journalists and other media actors from acts of violence, prohibiting, restraining or prescribing certain behaviour of the perpetrator. The injunctive and precautionary form of interim protection should offer immediate protection and be available without lengthy court proceedings or undue financial or administrative burden on the victim. They should be issued on an ex parte basis with immediate effect and should be available irrespective of, or in addition to, other legal proceedings. Effective, proportionate and dissuasive sanctions should be foreseen for any breach of such orders.

Early warning/rapid response mechanisms

- At a minimum, member states should promote awareness of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) hotline for journalists on dangerous assignments, the Press SOS hotline of Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and the press freedom hotline of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

- Set up and/or encourage set-up of 24/7 hotlines or 24-hour emergency contact points providing advice to journalists who have been threatened. If run by the state, meaningful civil society oversight and confidentiality or anonymity of the victim should be ensured.

- In addition to hotlines or emergency contact points, other early warning and rapid response mechanisms should be set-up with a view to giving visibility to threats to/attacks on journalists and other media actors, ensuring public awareness and dissuading potential perpetrators. Such early warning/rapid response mechanisms could take inspiration from the Council of Europe Platform to promote the protection of journalism and safety of journalists.

Cooperation with the Council of Europe Platform to promote the protection of journalism and safety of journalists

- At a minimum, states should ensure prompt and substantive responses to Platform alerts that concern them.

- To this end, identifying clear contact points responsible for ensuring swift and quality responses to alerts and developing a clear coordination mechanism among all relevant state authorities is highly desirable.

Protection of life from real and immediate risk

Effective and timely provision of police protection

- Ensure timely access to law enforcement authorities encompassing an individual risk assessment to identify specific protection needs. Upon receipt of a threat report, LEAs should systematically carry out assessment of the imminence of the risk, the seriousness of the situation and the risk of repeated violence, in order to manage the risk, devise a security plan and provide when needed protection to journalists and other media actors.

- Adequate information on available types of help and organisations providing such help should be given to the victim in a timely manner. This could include, for example, providing not just the name of a support service organisation, but handing out a leaflet that contains its contact details, opening hours and information on the exact services it offers. [1]

Comprehensive national protection mechanisms

- Where it is warranted, set-up at the national level a protection/safety mechanism with capacity to provide physical protection, with the participation of both LEAs and members of civil society and the media. It should serve especially journalists working on high risk matters such as corruption and organised crime and cover cases of attacks and attempted attacks, as well as credible threats. The mechanism should be autonomous, function in a transparent manner, and have a dedicated budget and sufficient funding to function effectively. The mechanism should also be backed by policy and legislation in order to be resilient to changes in the political agenda. It should analyse and adapt to the evolution of the risks present in the country and must be present and active in rural areas. The protection/safety mechanism, should in particular:

- Upn receipt of a threats report from journalists, systematically carry out an assessment of the imminence of the risk, the seriousness of the situation and the risk of repeated violence, in order to manage the risk, devise a security plan and provide when needed protection to journalists and other media actors.

- Ensure that victims are prvided with information on the different types of support services and legal measures available to them (including non-judicial avenues of redress) so that they are in a position to take fully informed decisions.

- Fllowing any determination that an individual needs protection, provide material measures of protection, including mobile telephones and bulletproof vests, as well as establish safe havens and emergency evacuation or relocation to safe parts of the country or other countries through a protection programme and police protection.[2] Arrangements t ensure the individual’s livelihood and appropriate medical and psychological care should also be ensured.

- Include an exit strategy elabrating when support to journalist should cease.

- Develop and implement measures for building trust in the mechanism by journalists and trust of all the stakeholders involved in each other, which is a precondition for its effective functioning.

- The set-up of a protection mechanism must go hand in hand with prevention and enhanced measures for investigation and prosecution of attacks. To this end, member states may identify existing structures or programmes within government institutions that protect other at-risk sectors of society and extend their mandate to cover the safety of journalists and other media actors.[3]

[1] “Adequate information” refers to information that sufficiently fills the victim’s need for information and “timely manner” means at a time when it is useful for the victims. See the Explanatory report to the Istanbul Convention regarding Article 19, page 78.

[2] Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on “The Safety of Journalists”, A/HRC/24/23, 1 July 2013, para. 63.

[3] “Defending Journalism: How National Mechanisms Can Protect Journalists and Address the Issue of Impunity - A comparative analysis of practices in seven countries”, International Media Support, 2017, page 52.

Other measures aimed at protection

- Set up safety funds supported by private donations to fund the costs for relocation to safety.

- If police protection is provided, the relevant personnel must be trained in human rights standards, and, where possible, special units should be tasked.

- Provide financial support for safety trainings designed specifically for female journalists and female media actors.