Preventing abuse of law

Indicators

Indicators

|

Risks |

Measures to avert/remedy the risks

|

|

Legislation and sanctions are applied in a discriminatory or arbitrary manner against journalists and other media actors. |

|

|

Frivolous, malicious or vexatious use of law and legal process to intimidate and silence journalists and other media actors. |

|

Discriminatory or arbitrary application of legislation or sanctions to silence journalists and other media actors (paragraph 13 of the Guidelines)

Reference texts and other relevant sources

Reference texts and other relevant sources

Statistics

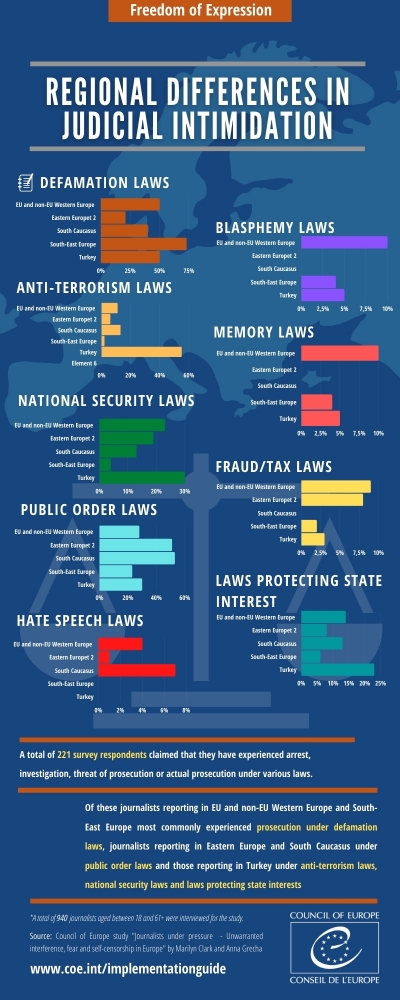

Misuse, abuse or threatened use of different types of legislation to prevent contributions to public debate, including defamation, anti-terrorism, national security, public order, hate speech, blasphemy and memory laws are unfortunately among common means of intimidating and silencing journalists and other media actors reporting on matters of public interest. According to the Council of Europe study “Journalists under Pressure”, 23% of interviewed journalists claimed to have experienced “judicial intimidation” or “judicial harassment” in the form of arrest, investigation, threat of prosecution or actual prosecution under a number of laws, including defamation laws, public order laws, anti-terrorism and national security laws. Additionally, certain legal provisions can themselves give rise to a chilling effect on freedom of expression and public debate.

General measures

Legislation often used to restrict freedom of expression includes, among others, public order, anti-terrorism, national security, hate speech, blasphemy and memory laws.

In line with the Court’s well-established case law, any restrictive measure must be prescribed by law, pursue at least one of the legitimate aims under Article 10(2) of the Convention and it must pass the proportionality test (the interference must be necessary in a democratic society and the measure(s) applied must be proportionate to the aim(s) pursued). In assessing the proportionality, domestic courts must assess all the circumstances of the case on a case-by-case basis, taking into account, among others, the context of the publication, the existence of public interest and the severity of the sanction.

Restraint in resorting to criminal proceedings

The Court has called for restraint in resorting to criminal proceedings, even when the protection of territorial integrity or national security or the prevention of crime or disorder are invoked, in cases where the publication at issue does not incite to violence[1] or instigate ethnic or other form of hatred (see, for instance, the Incal group of cases).[2] Criticism of governments and publication of information regarded by a country’s leaders as endangering national interests should not attract criminal charges for particularly serious offences such as belonging to or assisting a terrorist organisation, attempting to overthrow the government or the constitutional order or disseminating terrorist propaganda. This equally applies in the state of emergency.[3]

In order to prevent misuse/abuse of public order, anti-terrorism and national security laws to silence critical voices and unnecessary or disproportionate interference with freedom of expression, offences under these laws should be clearly defined and should not be over-broad.[4] In order to stem abuse/misuse of law, provisions should also be accessible to the person concerned, their consequences foreseeable and their compatibility with the rule of law ensured.[5] Furthermore, adequate procedural safeguards and effective remedies against abuse must be provided.

Protection of journalistic sources

The Court has repeatedly stressed that the protection of journalistic sources is one of the cornerstones of freedom of the press. Without such protection, sources may be deterred from assisting the press in informing the public about matters of public interest and as a result the vital public-watchdog role of the press may be undermined, and the ability of the press to provide accurate and reliable information may be adversely affected.[6] Misuse of public order laws, anti-terrorism and national security laws to access journalistic sources, either through surveillance measures or by compelling disclosure (or both, as in Telegraaf Media Nederland Landelijke Media B.V. and Others v. the Netherlands),[7] is a common example of interference in this sphere.

Disclosure orders placed on journalists have a detrimental impact not only on their sources, whose identity may be revealed, but also on the newspaper against which the order is directed, whose reputation may be negatively affected in the eyes of future potential sources. The detrimental impact further extends to the public who have an interest in receiving information imparted through anonymous sources and who are also potential sources themselves. Having regard to the crucial role of press freedom in a democratic society and the potential chilling effect of a disclosure order, such a measure cannot be compatible with Article 10 of the Convention unless it is justified by an overriding requirement in the public interest.[8]

Regarding surveillance measures, in Big Brother Watch and Others v. the United Kingdom[9] the Court found that while the operation of a bulk interception regime does not in itself violate the Convention, insufficient oversight of the selection process of surveillance subjects and a lack of adequate safeguards concerning the selection of communications data for examination do not satisfy the “quality of law requirement” and hence were in violation of Article 8. It further held that Article 10 was violated due to missing safeguards for journalistic sources in the operation of the bulk interception regime, and insufficient safeguards in the case of obtaining communications data from Communication Service Providers. According to established case law, searches of confidential journalistic material should be carried out only on the basis of a court order and in compliance with other substantive procedural safeguards, e.g. be subject to review by an independent and impartial body to prevent unnecessary access to information capable of disclosing the sources’ identity.

[1] “Incitement to violence” is interpreted by the Court as advocating recourse to violent actions or bloody revenge, justifying the commission of terrorist acts in pursuit of their supporters’ goals and that can be interpreted as likely to encourage violence by instilling deep-seated and irrational hatred towards specified individuals – see Sürek v. Turkey (no. 4) [GC], no. 24762/94, 8 July 1999, § 60.

[2] In the case of Incal v. Turkey (GC) (no. 22678/93, 9 June 1998) and a group of similar cases the Court has found that the applicants’ convictions on the account of breach of anti-terrorism law by having made, published or otherwise disseminated statements/publications were in violation of their right to freedom of expression (Article 10) because such statements/publications did not incite to hatred or violence.

[3] See, for instance, Sahin Alpay v. Turkey, no. 16538/17, 27 February 2001, § 172-184.

[4] For instance, in Gözel and Özer v. Turkey (nos. 43453/04 and 31098/05, 6 July 2010) the Court found that the wording of section 6(2) of the Turkish anti-terrorism law which sanctioned “anyone who print[ed] or publishe[d] statements or leaflets by terrorist organisations” and contained no obligation for the domestic courts to carry out a textual or contextual examination of the writings could not be reconciled with the right to freedom of expression.

[5] Ürper and Others v Turkey, nos. 14526/07, 14747/07, 15022/07, 15737/07, 36137/07, 47245/07, 50371/07, 50372/07 and 54637/07, 20 October 2009, §28-29.

[6] Goodwin v. the United Kingdom (GC), no. 17488/90, 27 March 1996, § 39.

[7] Telegraaf Media Nederland Landelijke Media B.V. and Others v. the Netherlands, no. 39315/06, 22 November 2012.

[8] Goodwin v. the United Kingdom (GC), no. 17488/90, 27 March 1996, § 39.

[9] Big Brother Watch and Others v. the United Kingdom, nos. 58170/13, 62322/14 and 24960/15, 13 September 2018, § 387.

Countering abuse of defamation legislation

Among the journalists interviewed for the study “Journalists Under Pressure” who had experienced judicial intimidation, the most common intimidation was reported under defamation laws.

Preventing award of disproportionate damages in civil actions

Law and practice allowing for excessive or disproportionate damages in civil actions have been found to produce a chilling effect on freedom of expression and on public debate.

In Tolstoy Miloslavsky v. the United Kingdom, the Court held that “under the Convention, an award of damages for defamation must bear a reasonable relationship of proportionality to the injury to reputation suffered” and found a violation of Article 10 having regard to the size of the award of damages, “in conjunction with the lack of adequate and effective safeguards against a disproportionately large award”. [1] In Independent Newspapers (Ireland) Limited v. Ireland, the Court found that unreasonably high damages for defamation claims can have a chilling effect on freedom of expression, therefore there must be adequate domestic safeguards so as to avoid disproportionate awards being granted. [2]

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) in its Resolution 1577(2007) “Towards decriminalisation of defamation” condemned abusive recourse to unreasonably large awards of damages and interest in defamation cases and, echoing the Court’s case law, pointed out that this may lead to a violation of Article 10 of the Convention.

The availability of a range of civil remedies as alternatives to damages, such as apologies or correction orders, can help provide a proportionate response to defamation and can enable a person’s reputation to be vindicated more promptly. The role of extra-judicial bodies, such as press councils, can also play a valuable role in achieving proportionality and timeliness, as has been noted by the Court.[3]

Abolishment of criminal sanctions for defamation

A chilling effect on freedom of expression can arise not only from any sanction, disproportionate or not, but also from the fear of sanction, even in the event of acquittal. Principle 34 of the Recommendation CM/Rec (2016)4 highlights that criminal sanctions have a greater chilling effect than civil sanctions. While the Court does not completely rule out the possibility of criminal sanctions for defamation, it attaches great importance to the nature of the sanction imposed in considering the proportionality of interference.[4]

Fear of imprisonment inevitably has chilling effect on the exercise of journalistic freedom of expression. In Mahmudov and Agazade v. Azerbaijan,[5] the Court stated that investigative journalists would be inhibited from reporting on matters of general interest if they run the risk of being sentenced to imprisonment for defamation. Recalling the Parliamentary Assembly’s Resolution 1577(2007) “Towards decriminalisation of defamation”, the Court has repeatedly urged member States whose legislation still provides for prison sentences for defamation, even if they are not actually imposed, to abolish them without delay.[6] A prison sentence for a press offence will be compatible with journalists’ freedom of expression as guaranteed by Article 10 of the Convention only in exceptional circumstances, notably where other fundamental rights have been seriously impaired, as, for example, in the case of hate speech or incitement to violence.[7]

Removing enhanced protection for public figures from criticism and public scrutiny

Defamation laws that are overly protective of reputational interests may also have a chilling effect on freedom of expression.

In Lingens v. Austria the Court found that the “limits of acceptable criticism are wider as regards public or political figures than as regards a private individual. In a democratic society, the government’s actions must be subject to the close scrutiny not only of the legislative authorities but also of the press and public opinion”.[8] As concerns heads of state, in Artun and Güvener v. Turkey, the Court ruled that a state’s interest in protecting the head of state “cannot justify conferring on him or her a privilege or special protection vis-à-vis the right to report and express opinions about him or her”.[9] Principles related to criticism aimed at heads of state apply not only to republican heads of state but also to non-elected monarchs.[10]

In Resolution 1577(2007) “Towards decriminalisation of defamation” PACE called on Council of Europe member States to remove from their defamation legislation any increased protection for public figures, in accordance with the Court’s case law.

Countering abuse of law and/or legal process in defamation cases

Principle 36 of Recommendation CM/Rec(2016)4 warns that frivolous[11], vexatious[12] or malicious[13] use of law and legal process, with high legal costs required to fight such lawsuits, can become a means of pressure and harassment of journalists and other media actors and create a chilling effect on freedom of expression.

One such example is forum shopping in defamation cases (also known as “libel tourism” [14]), when the claimant acts with a malicious intent or abuses his/her right to access to court. This phenomenon has been identified by the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers as a major challenge to free expression, access to information and to media pluralism and diversity due to its chilling effect.[15] In addition, it negatively impacts on other human rights, such as the right to a fair trial (Article 6) and the right to an effective remedy (Article 13).[16]

Forum shopping is made possible by the differences between national defamation laws, conflict of law rules, rules on jurisdiction, rules on recognition and enforcement of foreign judgements and, more generally, by globalisation, given that content on the internet becomes instantly accessible in multiple jurisdictions. The Council of Europe Study on “Liability and jurisdictional issues in online defamation cases” identifies 15 good practices in Council of Europe member States to mitigate factors that are conducive to forum shopping in defamation cases.[17] Rules and standards regarding criminal and civil liability in order to prevent “libel tourism” are also found in the Joint Declaration on freedom of expression and the internet.[18]

Ensuring the principle of equality of arms is of crucial importance in tackling misuse and abuse of law and legal process. Procedural safeguards enabling defendants to effectively counter frivolous, vexations and malicious lawsuits may include truth, public-interest and/or fair comment defences.[19] As harassment arising from abuse of law and legal process can prove particularly acute for journalists and other media actors who do not benefit from the same legal protection or financial and institutional backing as those offered by large media organisations, states are required to take appropriate measures to ensure that each side is afforded a reasonable opportunity to present his or her case.[20]

An additional response to such vexatious forms of litigation is anti-SLAPP[21] legislation that provides remedies to the defendant to counter frivolous, vexatious or malicious lawsuits. Most commonly, it allows for bringing a motion to strike a case brought against him/her because it involves speech on a matter of public concern. The plaintiff then has the burden of showing a probability that they will prevail in the suit - meaning they must show that they have evidence that can result in a verdict in their favour.

[1] Tolstoy Miloslavsky v. the United Kingdom, no. 18139/91, 13 June 1995, §§ 49, 51.

[2] Independent Newspapers (Ireland) Limited v. Ireland, no. 28199/15, 15 June 2017, § 104.

[3] See for instance Stoll v. Switzerland [GC], no.69698/01, 10 December 2007.

[4] See for instance Radio France and Others v. France, no. 53984/00, 30 March 2004, § 40; Lindon, Otchakovsky-Laurens and July v. France (GC), nos. 21279/02 and 36448/02, 22 October 2007, § 59.

[5] Mahmudov and Agazade v. Azerbaijan, no. 35877/04, 18 December 2008, § 49.

[6] See for instance Mariapori v. Finland, no.37751/07, 6 July 2010, § 69; Niskasaari and Others v. Finland, no. 37520/07, 6 July 2010, § 77; Saaristo and Others v. Finland, no. 184/06, 12 October 2010, § 69 and Ruokanen and Others v. Finland, no. 45130/06, 6 April 2010, § 50.

[7] See for instance Cumpănă and Mazăre v. Romania [GC], no. 33348/96, 17 December 2004, § 115; Ruokanen and Others v. Finland, no. 45130/06, 6 April 2010, § 50.

[8] Lingens v. Austria, no. 9815/82, 18 July 1986, § 42.

[9] Artun and Güvener v. Turkey, no. 75510/01, 26 June 2007, § 31.

[10] Stern Taulats and Roura Capellera v. Spain, nos. 51168/15 and 51186/15, 13 March 2018, § 39.

[11] A frivolous claim or complaint is one that has no serious purpose or value. Often a "frivolous" claim is one about a matter so trivial or one so meritless on its face that investigation would be disproportionate in terms of time and cost. The implication is that the claim has not been brought in good faith because it is obvious that it has no reasonable prospect of success and/or it is not a reasonable thing to spend time complaining about.

[12] A vexatious claim or complaint is one (or a series of many) that is specifically being pursued to simply harass, annoy or cause financial cost to their recipient (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frivolous_or_vexatious).

[13] Malicious use of the law and legal process is initiating a criminal prosecution or civil suit against another party with malice and without probable cause (https://www.merriam-webster.com/legal/malicious%20prosecution).

[14] “Libel tourism” is a form of forum shopping whereby a complainant files a defamation complaint with the court thought most likely to provide a favourable judgment even when there is no or only a tenuous connection between the legal issue and the jurisdiction.

[15] Declaration by the Committee of Ministers on the Desirability of International Standards dealing with Forum Shopping in respect of Defamation, adopted on 4 July 2012, pt.5.

[16] Council of Europe Study on “Liability and jurisdictional issues in online defamation cases”, DGI(2019)04.

[17] Council of Europe Study on “Liability and jurisdictional issues in online defamation cases”, DGI(2019)04.

[18] Joint Declaration on freedom of expression and the internet, adopted on 1 June 2011 by the United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Representative on Freedom of the Media, the Organization of American States (OAS) Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information, point 4.

[19] For an overview of defences typical for defamation cases, please see “Freedom of Expression and Defamation - A Study of the case law of the European Court of Human Rights” by Tarlach McGonagle, Council of Europe, pp. 43-45 and 51.

[20] Paragraph 36 of the Principles section of Recommendation CM/Rec(2016)4.

[21] SLAPP is an acronym for Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation. According to the Public Participation Project based in the United States, such lawsuits target those who speak in the public interest with a purpose of silencing and harassing them. “SLAPP filers don’t go to court to seek justice. Rather, SLAPPS are intended to intimidate those who disagree with them or their activities by draining the target’s financial resources. While SLAPP lawsuits often do not lead to a final judgment against the defendant, they do have a grave chilling effect on the journalist or other media actor.”

Valuable practices and initiatives which provide guidance in this area

Valuable practices and initiatives which provide guidance in this area

Countering abuse of defamation legislation

Comprehensive legal reforms introducing different types on measures

- In England and Whales, the 2013 Defamation Act aims to curb vexatious use of defamation lawsuits, notably by introducing a “serious harm threshold". The Act provides that "a statement is not defamatory unless its publication has caused or is likely to cause serious harm to the reputation of the claimant". This concept is intended "to raise the bar" as to what the courts will consider as a viable libel complaint. There is also potential for trivial cases to be struck out on the basis that they are in abuse of process because so little is at stake. In Jameel v. Dow Jones & Co it was established that there needs to be a real and substantial tort. The Act also targets “libel tourism” by tightening the test for claims involving those with little connection to England and Wales being brought before the courts. It also provides for a single-publication rule to prevent repeated claims against a publisher about the same material, meaning that the limitation period for a defamation action must be calculated only from the date of the first publication.

- In Iceland, further to the Iceland’s Modern Media Initiative (IMMI), the Prime Minister has appointed a committee on legislative reform in the field of freedom of expression, media and information. The committee is tasked with reviewing and improving existing bills, including those on defamation, information law, hate speech, data storage, and the responsibility of host providers and evaluate which legislative changes may be desirable in the field of freedom of expression, media and information. The Committee has already finalised bills and/or amendments in order to, among others: remove criminal liability for defamation, replacing it with civil liability in the form of damages/compensation; introduce a number of defences to exclude liability in certain cases; remove increased protection for the reputation of public figures; impose stricter requirements for hate speech to be considered punishable; protect whistle-blowers; strengthen the right of the public to access information; protect journalists from defamation proceedings and shifting liability to the employer.

Removing enhanced protection for public figures from criticism and public scrutiny

In Serbia, further to two judgments by the ECHR (Lepojić v. Serbia and Filipović v. Serbia), the Supreme Court adopted in 2008 a legal opinion stating that criticism of public personalities is more acceptable than that of private persons.

Countering abuse of law and/or legal process in defamation cases

- In the UK, the Government has issued a Guidance Note on Vexatious Litigants, explaining when a claim can be considered vexatious and describing possible civil, as well as criminal law remedies.

- Under French law, a defendant in defamation proceedings is provided with the truth-defence. Also, under the jurisprudence of the Court of Cassation, defendants in defamation cases can argue a legitimate aim pursued and general public interest of the publication, good faith, the absence of animosity or personal attack and the seriousness of the inquiry.

- In the USA, an example of anti-SLAPP law is the State of Oregon’s anti-SLAPP statute. Under this statute, a defendant’s motion to dismiss the case is granted if the defendant meets the initial burden of making a prima facie showing that the claim arises out of a statement, document or conduct involving the exercise of the right of free speech in connection with a public issue or an issue of public interest. If this requirement is met, the burden shifts to the plaintiff who will need to demonstrate that there is a probability that he/she/it will prevail on the claim, by presenting substantial evidence to support a prima facie case. If the plaintiff meets this burden, the court shall deny the defendant’s motion.

- In the EU, a proposal for a directive to counter vexatious lawsuits/SLAPP litigation has been presented by six members of Parliament, encompassing, among others: the possibility for investigative journalists and independent media to request that vexatious lawsuits in the EU be expediently dismissed and claim compensation; the establishment of punitive fines on firms pursuing these practices when recourse is made to jurisdictions outside the EU; the setting up of a SLAPP fund to support investigative journalists and independent media that choose to resist malicious attempts to silence them and to assist in the recovery of funds due to them; the setting-up of an EU register that names and shames firms that pursue these abusive practices.

Suggestions for implementation

Suggestions for implementation

General measures

- Review and elimination of overbroad definitions in defamation, anti-terrorism, national security, public order, hate speech, blasphemy and memory laws. To avoid abuse, key terms and concepts must be defined with sufficient precision.

- Restraint, in line with the ECHR case-law, in resorting to criminal proceedings/criminal sanctions for press offences (under public order, anti-terrorism, national security and other laws), even when territorial integrity/national security are invoked.

- Putting in place adequate procedural safeguards and effective remedies against abuse of these laws.

Protection of journalist sources

- Introduce safeguards for journalistic sources, such as the guarantee of review of disclosure decisions by an independent and impartial body to prevent unnecessary access to information capable of disclosing the sources’ identity. The review body must be in a position to weigh the potential risks and respective interests prior to any disclosure. Its decision should be governed by clear criteria, including whether less intrusive measures would suffice.

Countering abuse of defamation legislation

- Review of domestic defamation legislation to ensure that:

- awards of damages are not disproportionally large and there are adequate and effective domestic safeguards against too large awards;

- they do not, except for exceptional circumstances and in line with relevant ECHR case law, provide for prison sentences;

- there is no increased protection for public figures. In particular, heads of state/monarchs are not conferred a privilege or special protection vis-à-vis the right to report and express opinions about him/her;

- freedom of expression safeguards that conform to European and international human rights standards, including truth/public-interest/fair comment defences are provided either in the law or in judicial practice;

- a range of civil remedies is available as an alternative to damages in appropriate cases, such as apologies or correction orders; fast-track or low-cost measures are available;

- extra-judicial bodies, such as press councils, are promoted with a view to providing a proportionate response to defamation.

Countering abuse of law and/or legal process in defamation cases

- Adoption of legislative and/or other measures to prevent, with due respect to the independence of justice, the abuse of the judicial process and to prevent “libel tourism”, in particular:

- curts and tribunals should have jurisdiction over a case only if there is a strong connection between the case and the jurisdiction they belong to;

- curts and tribunals should seek to identify and recognise foreign declaratory judgements that are aimed at preventing or stopping abuse of legal procedure or any other action by the claimant that could be qualified as forum shopping;

- curts and tribunals should generally refuse, on the basis of the public order exception, to recognise or enforce foreign judgments that grant manifestly disproportionate damages awards that were rendered in breach of due process of law or as the result of an abuse of rights;

- curts should consistently apply the res judicata exceptin when asked to recognise and enforce a foreign judgment that is irreconcilable with another decision from another state’s court on a case involving the same cause of action and between the same parties;

- specific and reasnably short limitation periods for defamation actions should be set out clearly in national law;

- a single publicatin rule should apply and determine the starting date of the limitation period for defamation cases;

- curts and tribunals should lift limitation periods upon request by one of the parties, provided that objective and clearly defined conditions, as set out in relevant legislation, are met;

- where the burden f proof is on the defendant, available defences should not impede the reversal of the onus of proof on the claimant or to make such reversal unreasonably difficult;

- curts and tribunals should deliver judgments in absentia nly when proper servicing of international proceedings is effectively guaranteed;

- the amunt of damages granted by court in defamation proceedings should be strictly proportionate to the harm suffered by the claimant;

- punitive damages, where available under the member States’ legal framewrk, are only allowed if strict and clearly defined conditions are met;

- appeals slely based on the amount of damages should be allowed;

- curts should rely on the prohibition of abuse of rights to address the cases of manifest forum shopping;

- where applicable, curts should scrutinise under the frum non conveniens dctrine the relevant factual elements of the case, while identifying the forum best placed to hear it;

- the prximity (strong connections) principle should apply in determining the law applicable to a defamation case.

- Development of anti-SLAPP legislation to allow defendants in defamation cases to bring a motion to strike a case brought against him/her because it involves speech on a matter of public concern.

- Introducing legal aid schemes for journalists in order to ensure that they have a reasonable opportunity to present their cases.

- Exploring NHRIs role in training judges and prosecutors in order to avoid arbitrary application of restrictive legislation vis-à-vis journalists and other media actors.