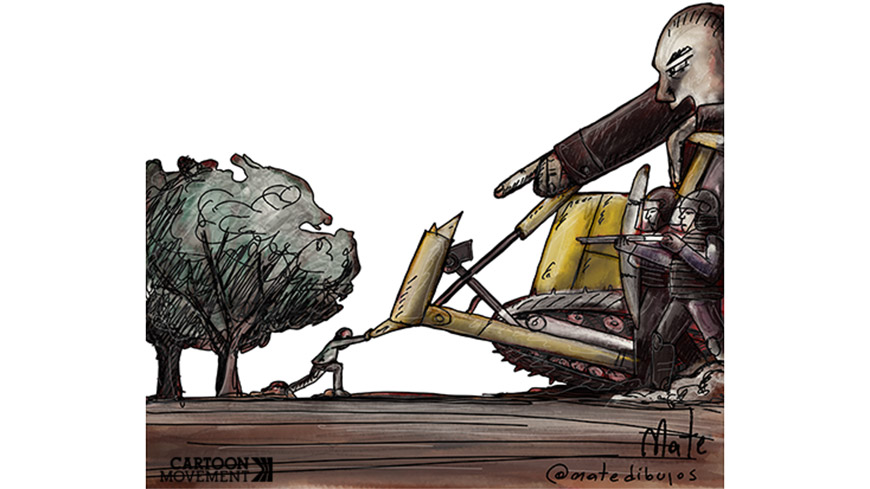

Environmental pollution, climate change and biodiversity loss are among the most urgent existential threats to humankind and to human rights. In response, many people in Europe and beyond have seen fit to take to the streets and to try new, often disruptive, forms of peaceful protest to demand more resolute government action on issues relating to the protection of nature and the environment, health, and climate change. However, their legitimate demands and concerns are increasingly being met with repression, criminalisation, and stigmatisation.

Environmental protest on the rise

Europe has a rich history of environmental activism and climate action in a variety of forms ranging from public demonstrations, marches, sit-ins and school strikes to public petitions, boycotts, and climate litigation. Public protest has in particular been seen by environmental defenders as being among the most effective and sometimes indispensable tools for raising public awareness in the hope of effecting change. Protests dedicated to environmental issues or directed against government inaction on climate change regularly make international headlines, especially ahead of and during the annual United Nations climate change conferences (COPs).

Over the past years, these protests have been accompanied by a burgeoning sentiment of frustration and powerlessness, especially among the youngest generations, at the apparently inadequate government action in the face of an impending climate catastrophe. Galvanised by compelling scientific data that lays out in all evidence the degree of global environmental pollution, the rapid decline in biodiversity, and the dire consequences of further inaction, more and more people are turning to nonviolent environmental direct action. This includes, for example, blocking traffic by sit-ins or slow walking; locking or gluing oneself to places, cars, or other people; interrupting public events; and new methods, such as protesting in museums and art galleries and smearing famous works of art or places of culture with paint or food.

In recent months there has been an intensification in the number, scale, and variety of forms of public protest by environmental defenders and activists. In Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, for example, protesters blocked streets, motorways, railway tracks, construction sites, and an airport runway. In various European countries , climate activists smeared or glued themselves to the frames of famous paintings, and interrupted art performances and sporting events.

To some participants, these forms of public protest seem better suited to amplify their message and to reach a wider audience. Others see them as a measure of last resort in the face of an urgency to act. This is especially true of climate activists, who are often denied a place at the policy table, denied transparency about environmentally damaging decision-making processes or projects, refused access to climate conferences, or relegated to remote, out-of-sight authorised protest areas. It is also true of many young people who, as I have found in the context of my country work, have limited possibilities of formally participating in political decision-making and who consequently feel compelled to rely on demonstrations or protests to make their voices heard.

Repression and stigmatisation of peaceful environmental protest

Regardless of its source or justification, violence is never a means of solving social or political issues. However, the above-mentioned environmental protests, which by their very nature and design tend to be disruptive, have been for the most part, with very rare exceptions, peaceful and non-violent. Still, in many places across Europe, they are met with repressive action, including heavy-handed policing, physical violence, detention – at times, pre-emptive – and criminalisation of protesters.

By way of an example, in recent months peaceful environmental protesters were pepper sprayed by police in Austria, manhandled and injured by riot police in France, dispersed in Georgia, and subjected to arrests and detention in Finland, the Netherlands, and Serbia. Activists who blocked a street in the centre of Munich were placed in preventive police detention for 30 days, made possible by legislation amended in 2021, and the homes of many climate protesters were searched across Germany. In several European countries, courts have imposed prison sentences, with and without probation, as well as penalties of community service, on environmental campaigners. Environmental activists were also targeted by vexatious lawsuits – so-called SLAPPS (strategic lawsuits against public participation), for instance recently in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In France, Spain and the United Kingdom, journalists and media workers were arrested, investigated and, in some cases, criminally charged in the context of environmental protests they were covering.

In some countries, reactions to environmental protests involved proposals to make existing laws and regulations governing public protest more restrictive. In the United Kingdom, legislative amendments which propose to introduce sweeping new police powers to stifle protests have been denounced as being largely targeted at the country’s climate protesters and raise concern about a chilling effect on the exercise of the right to protest in general. In some places, opinion-makers or police union representatives have called for harsher penalties for climate activists, including preventive detention and longer prison terms, in an effort to put a stop to disruptive protests.

I already expressed concern at the shrinking space for freedom of peaceful assembly and the threats facing environmental activism in Europe in my Human Rights Comments published in 2019 and in 2021 as well as in my 2021 roundtable report dedicated to environmental rights activism and advocacy. Nonetheless, this repressive trend appears to keep intensifying.

Stigmatisation and accusations of extremism, vandalism, or endangering life

Furthermore, as I already noted in my previous Comments, participants of environmental and climate protests have to contend with increasing stigmatisation. Those who are at the forefront of climate action protests have often been maligned, likened to extremists and referred to as ‘(eco-)terrorists’, ‘eco-zealots’, ‘criminals’, a ‘selfish minority’, or other derogatory terms. Environmental protests have been equated with unlawful activity, labelled ‘eco-vandalism’, or even likened to ‘terrorism’ by some politicians, media outlets, opinion-makers, and Internet trolls, in an attempt to set the general opinion against environmental defenders and fuel resentment against their cause, sometimes leading to violence being used against them.

Environmental protesters have also been unfairly accused of criminal negligence such as, for example, endangering human life by delaying emergency services during road blockades. Much criticism has also been directed at climate activists in relation to the harm allegedly caused to works of art targeted by protests in museums and art galleries. However, such accusations have been vehemently disputed by protesters, who claim to take special care both to avoid creating traffic hazards during sit-ins on public roads, and to deliberately select works of art shielded by protective glass panels during art gallery protests.

In this way, in Germany, climate protesters who blocked a motorway were accused of contributing to the death of a cyclist in a nearby accident, and widely condemned. The authorities, however, eventually determined that the protesters had not been responsible for the cyclist’s death. Besides, by most accounts, none of the works of art targeted have actually been harmed by climate activists protesting in museums and galleries (although some curators did report minor damage to property). While some have warned that targeting works of art could have the unintended consequence of leading museums and galleries to limit the public’s access to art, as of yet, this threat does not appear to have materialised either.

Although some commentators have criticised new forms of environmental protest for being misguided or ineffective, or even argued that they do harm to the protesters’ own cause, others have credited them with successfully drawing public attention to climate change and raising the profile of environmental concerns within general public opinion. It is encouraging to see that a council of directors of museums and galleries, in particular, while expressing concern about the safety of their collections, also expressly acknowledged the validity of climate activists’ concerns in the face of “an environmental catastrophe that threatens life on Earth”.

Council of Europe standards on protecting the right to peaceful assembly and freedom of expression

The right to freedom of peaceful assembly and freedom of expression, which include the right to demonstrate and to protest in defence of the natural environment, are among the cornerstones of democracy. These rights are essential to a healthy pluralist democracy and human dignity because they enable people from diverse backgrounds and perspectives to express their views, hold their governments to account and participate in or stimulate public debate. In a democracy, public authorities must facilitate peaceful assembly and free expression, not stifle them.

The European Court of Human Rights (the Court) has consistently afforded a high level of protection to the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and freedom of expression in its case-law concerning environmental demonstrations and campaigns. Similarly, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to peaceful assembly and of association has stressed the crucial role that peaceful assembly has for climate activists and for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. The interplay between freedom of peaceful assembly, freedom of expression, and the protection of the environment is further stressed by the Framework Principles on Human Rights and the Environment and the Aarhus Convention Special Rapporteur on environmental defenders.

As the Court has emphasised in its case-law on the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and to freedom of expression, these rights are not absolute and do not confer an unfettered choice of forum. Not all forms of protest may be permissible, and some may be rightfully challenged by the authorities for the prevention of disorder or crime and for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others where demonstrators engage in acts of violence. The intentional serious disruption to ordinary life and to the activities lawfully carried out by others, to a more significant extent than that caused by the normal exercise of the right of peaceful assembly in a public place, might in some cases justify the imposition of penalties.

Nevertheless, it must be stressed that public authorities do not enjoy unlimited discretion to regulate the exercise of these rights. Any restrictions must be prescribed by law, necessary, proportionate, non-discriminatory, and subject to independent judicial review. They must be interpreted narrowly and not be used to undermine the essence of the rights or to criminalise peaceful demonstrators.

The risk of disruption to public life is inherent to the nature of public protest. Many of the emerging forms of environmental protest may indeed cause disruptions to ordinary life, including to road traffic. This may understandably disturb those uninvolved, but it does not automatically render an assembly or a form of public expression unlawful. The term ‘peaceful assembly’ should be interpreted to include conduct that may annoy or give offence to others, as well as actions that temporarily hinder, impede, or obstruct the activities of third parties. It should also be kept in mind that not every act of defiance by protesters constitutes violence, and that peaceful participants may not be held responsible for reprehensible acts committed by others. Peaceful demonstrations should not, in principle, be rendered subject to the threat of criminal sanctions.

Turning back the repressive tide

What we are seeing in many places in Europe and elsewhere in the world today is a clear asymmetry between the responses of many state authorities and the standards that safeguard the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and freedom of expression. The increasing trend of repression of those rights in Europe is the wrong answer and it must be reversed.

Instead of repressing or vilifying those who legitimately make use of their right to freedom of peaceful assembly and freedom of expression, or introducing new legal restrictions on the exercise of those rights, public authorities in Council of Europe member states should ensure that they can be exercised safely, while protecting other legitimate aims, including the rights and freedoms of others. In carrying out this balancing act, the authorities should constantly be guided by the principle that safeguarding the right to peaceful assembly and freedom of expression is the rule and any restrictions to those rights the strict exception. Member states should steer clear of the temptation to pass laws that could lead to further restrictions of those rights. As stated by the European Court of Human Rights, “any measures interfering with freedom of assembly and expression other than in cases of incitement to violence or rejection of democratic principles – however shocking and unacceptable certain views or words used may appear to the authorities – do a disservice to democracy and often even endanger it”.

Violence against peaceful participants of environmental protests, in particular, must not be tolerated. Public authorities are under the legal obligation to protect peaceful environmental protesters from harm, including by non-state actors, such as bystanders or private security actors. As per the case-law of the European Court of Human Rights, the Venice Commission and OSCE/ODIHR Guidelines on freedom of peaceful assembly, and my earlier recommendations, policing of public assemblies must be human rights compliant. Journalists and media workers covering environmental protests must be protected from harm and allowed to pursue their work safely and without undue interference. National human rights institutions, who have committed to taking up the difficult situation of environmental defenders facing persecution and violence, also have an important role to play in defending environmental activists’ rights to freedom of assembly and expression.

Criminalising, silencing, or shutting out environmental protesters does not only violate their human right to peaceful assembly. It is also counterproductive. Protests by disgruntled individuals, of which so many are disenfranchised children and young people, have already become a steady feature of our daily life. If the root causes underlying their concerns are left unaddressed, sanctions are unlikely to deter them; if anything, repression will only fuel their frustration and strengthen their resolve. It may also lead many of them to grow disillusioned in the capacity of democratic institutions to respond to the climate emergency and other pressing environmental challenges.

Alternatives to mounting restrictions do exist and should be used. The cracking down on peaceful protest must urgently give way to more genuine, quality social dialogue on environmental matters, including ways of addressing climate change. Concrete solutions must be identified to give environmental defenders a seat at the policy table. Public authorities and private businesses should ensure that genuine and effective opportunities are afforded to environmental organisations, communities and concerned persons, including children and young people, to take part in decision-making on all laws, policies and projects which may have an environmental impact, in a transparent manner. States should also consider lowering the voting age, where applicable, to enhance the effective participation of children in public life more generally. Finally, we need to urgently see more decisive, genuine, and ambitious government action on climate change and environmental pollution, building on the example given by the recent legal recognition at the global level of the right to clean and healthy environment by the Human Rights Council in October 2021 and by the UN General Assembly resolution, passed in July 2022.

Lastly, it is necessary to once more repeat that the verbal stigmatisation of environmental defenders and climate activists is a harmful practice that must not be allowed to take root. Peaceful protest, whatever its form or forum, is not, and must never be equated with unlawful activity, and terrorism in particular. As has been rightly pointed out by the Aarhus Convention Special Rapporteur on environmental defenders, Michel Forst, “[t]hese discourses and the accompanying vilification campaigns are a threat to democracy”.

Many of the advances in freedom and dignity in the history of humankind have been achieved thanks to the determination of people who had the courage to take to the streets and embrace civil disobedience to challenge the status quo, insist on respect for human rights, and demand reforms. The end of slavery, improved labour conditions, or the progress made in advancing women’s rights, are just a few examples of such advances. Environmental human rights defenders and climate activists are part of this long and inspiring tradition of defenders of human rights and freedoms. They rely on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and to freedom of expression as a means of channelling legitimate concerns about the lack, or slow pace, of progress towards addressing the climate emergency and other pressing environmental concerns. These are issues that affect us all in that they concern our human rights, well-being, and future. Those who raise them deserve our sympathy and support – not repression or resentment.

Dunja Mijatović