Training on the protection of journalists

Training on the protection of journalists (paragraph 12 of the Guidelines)

Member States are urged to develop protocols and training programmes for all State authorities who are responsible for fulfilling State obligations concerning the protection of journalists and other media actors. Those protocols should be adapted to the nature and mandate of the State agency personnel in question, for example, judges, prosecutors, police officers, military personnel, prison wardens, immigration officials and other State authorities, as appropriate. The protocols and training programmes should be used to ensure that the personnel of all State agencies are fully aware of the relevant State obligations under international human rights law and humanitarian law and the actual implications of those obligations for each agency. The protocols and training programmes should be informed by an appreciation of the important role played by journalists and other media actors in a democratic society and of gender-specific issues.

Indicators

Indicators

|

Risks |

Measures to avert/remedy the risks |

|

State authorities responsible for tasks concerning the protection of journalists and other media actors are not duly informed about of their relevant human rights obligations and the specificities of the media sector. |

|

Reference texts and other relevant sources

Reference texts and other relevant sources

Aim of the training

In the context of the UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity, training of law enforcement, judicial and other public officials responsible for fulfilling state obligations concerning the protection of journalists and other media actors has been identified as one of the key actions[1] to strengthen the implementation of the Plan and as one of the national indicators to measure progress in the implementation. The aim of such training is to raise awareness of relevant authorities on the scale and urgency of the problem, change their outlook and significantly improve the nature and quality of the support provided to victims. Training should be adapted to the mandate of public officials and reflect both regional standards (notably, Council of Europe standards and in particular Recommendation CM/Rec(2016)4),[2] and other international human rights standards.[3]

[1] See “Strengthening the Implementation of the UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity”, Consultation outcome document, 16 August 2017, page 6.

[2] For a list of the most relevant Council of Europe instruments providing guidelines on reinforcing and safeguarding the role of journalists, their rights and freedoms, please see the study “Journalists Under Pressure - Unwarranted interference, fear and self-censorship in Europe”, Marilyn Clark and Anna Grech, 2017, Council of Europe, pp. 16-18. The recommendations of the Committee of Ministers are inspired by the Convention, as interpreted in the case-law of the Court.

Training programmes for state authorities and agents

Principle 16 of Recommendation CM/Rec(2016)4 stresses that in the course of their work, journalists and other media actors often face specific risks and discrimination on different grounds (gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, colour, language, religion, political or other opinion, etc). Moreover, the pursuit of particular stories and coverage of certain sensitive issues[1] can also expose journalists and other media actors to threats, attacks, abuse and harassment by state and/or non-state actors (including terrorist or criminal groups). These vulnerabilities should be taken into account when affording preventive or protective measures, at the investigation phase and also when devising specific protocols and training programmes for state agents. The protocols and training programmes for law enforcement agencies, for instance, should stress that investigations opened in cases of violence/threats against a journalist must take into due account evidence showing a link to the journalist’s professional activities. More generally, training of relevant state agents should take into account the important role played by journalists and other media actors in a democratic society in line with the Court’s jurisprudence[2] and gender-specific issues.

Gender-specific risk factors

In her Communiqué on the growing safety threat to female journalists online, the former OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, Ms Dunja Mijatović, has highlighted the growing number of reports of female journalists and bloggers being attacked on social media.[3] Reports show that two thirds of women journalists suffer gender-based online attacks and that female journalists and television news presenters receive about three times as much online abuse as their male counterparts.[4] In a survey conducted among 597 women journalists and media workers by Trollbusters and the International Women’s Media Foundation, 90% of respondents indicated that online threats had increased over the past five years.[5]

Online attacks present themselves in the form of sexual harassment and intimidation and even threats of rape and sexual violence and target women journalists because they are women. An International Federation of Journalists’ Survey showed that while half of such cases have been reported, the harasser was identified or brought to justice in only 13% of the cases. Accordingly, the former OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media has called for better training for law enforcement officials in order to improve their understanding of how to investigate threats and other criminal offenses that take place online (and are gendered), highlighting that threats and harassment online that amount to criminal offenses must be prosecuted and treated like offline offenses. Training and guidance should also emphasise that threats to life and physical integrity, including rape threats, should be prioritised for prosecution.[6]

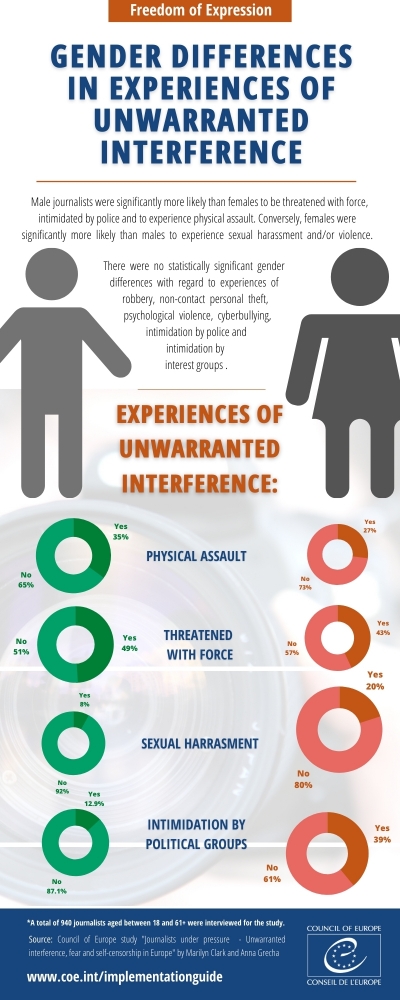

Off-line, women journalists are significantly more likely than men to experience sexual harassment and/or sexual violence as shown by the Study “Journalists Under Pressure”. Article 15 of the Istanbul Convention requires parties to the Convention to provide/strengthen training for those professionals (including public authorities) who deal with victims of violence against women[7] on the prevention and detection of such violence, equality between women and men, the needs and rights of victims, as well as how to prevent secondary victimisation.

[1] Such as sensitive political, religious, economic or societal topics, including misuse of power, corruption and criminal activities.

[2] The role of the press as “public watchdog” was first emphasised by the Court in Lingens v. Austria (no. 9815/82, 18 July 1986). In Bladet Tromsø and Stensaas v. Norway (GC) (no. 21980/93, 20 May 1999), the Court highlighted once again “the essential function the press fulfils in a democratic society”, stating that “although the press must not overstep certain bounds, in particular in respect of the reputation and rights of others and the need to prevent the disclosure of confidential information, its duty is nevertheless to impart – in a manner consistent with its obligations and responsibilities – information and ideas on all matters of public interest”.

[3] Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the Representative on Freedom of the Media, Dunja Mijatović, Communiqué on the growing safety threat to female journalists online, 02/2015.

[4] See “New Challenges to Freedom of Expression: Countering Online Abuse of Female Journalists”, OSCE, 2016, page 41.

[5] It showed, in particular, that two out of three respondents had been threatened or harassed online at least once and that this resulted in self-censorship in 40% of cases.

[6] OSCE, the Representative on Freedom of the Media, Dunja Mijatović, Communiqué on the growing safety threat to female journalists online, 02/2015, page 44.

[7] Under the Istanbul Convention, these include but are not limited to sexual harassment, sexual violence, including rape, psychological violence, etc.

Pratiques et initiatives utiles qui fournissent des orientations dans ce domaine

Pratiques et initiatives utiles qui fournissent des orientations dans ce domaine

Training programmes for state authorities

- In Sweden, the police authority has launched on-line training for police officers who receive reports, in order to increase their ability to deal with hate crimes and crimes against democracy. In addition, the Uppsala University has been commissioned to develop a five-days specialist course for police officers who work on hate crimes and crimes against democracy addressing: freedom of speech, freedom of the press and the fundamental rights and freedoms of journalists, opinion leaders and politicians; how police officers can gain and secure trust among vulnerable groups and individuals; how to improve the investigation of hate crimes and crimes against democracy and stem impunity.

- Through the UNESCO MOOC programme, training on “The International Legal Framework of Freedom of Expression, Access to Information and Protection of Journalists” has been provided to over 3,000 judges and judicial-sector operators in Latin America.[1]

- In France, the rights of the press and the respect of journalistic sources is covered both by initial training, as well as by continuous training of judges.

- In Ukraine, a number of training sessions for LEAs, prosecutors and judges have been organised in the course of 2017 and 2018, including in the context of Council of Europe sponsored events on the rights of journalists, related changes in the criminal and criminal procedural law, the investigation of crimes committed against journalists.

Involvement of non-state actors

- In the Netherlands, in July 2018 an agreement was reached between the national police, the public prosecutor’s office, the Dutch Association of Journalists (NVJ) and the Dutch Society of Chief Editors to counter threats and violence against journalists. Its aim is to improve awareness raising among law enforcement services on the issue of safety of journalists and to offer training and concrete guidelines for law enforcement to better respond to threats against the media. As a result of this agreement, the police and the public prosecutor have committed to give priority to incidents concerning journalists.

- In Serbia, an agreement on “Cooperation and measures to increase the level of safety of journalists” was signed by the Prosecutor’s office, the Ministry of Interior and journalists and media associations in December 2016. It encompasses training for journalists, media owners, prosecution and law enforcement officials in order to improve their knowledge on the protection of journalists, including international standards.

Suggestions pour la mise en œuvre

Suggestions pour la mise en œuvre

Training programmes for state authorities

- The training for police officers, prosecutors, judges and other relevant state authorities and agents should be informed by the case-law of the ECHR and Council of Europe’s standards, in particular by Recommendation CM/Rec(2016)4. Specific attention should be given to:

- raising awareness abut the important “public watchdog” role played by journalists and other media actors in a democratic society;

- the role played by journalists and other media actors in a democratic society by cvering public demonstrations, reporting from conflict zones and in times of crisis, including in the state of emergency and ways to prevent any hindrance to such coverage (see Section II (D) of this Implementation Guide);

- the right of journalists and other media actors not to reveal their confidential sources of information and the necessary procedural safeguards (see Section II (C) of this Implementation Guide);

- the fact that in the curse of their work, journalists and other media actors often face specific risks and discrimination on different grounds and that the pursuit of particular stories can also expose them to threats, attacks, abuse and harassment by state and/or non-state actors, including terrorist or criminal groups (see Sections II(A) and II (E) of this Implementation Guide).

- the prevention and detection of violence against women, equality between women and men, the needs and rights of victims, as well as how to prevent secondary victimisation;

- the need to ensure timely access to law enforcement authorities when there is a serious risk/threat of violence/attack against journalists and other media actors, the provision of information on the assistance, support, protection and compensation that victims can obtain as of their first contact with LEAs and the need to issue injunctive/precautionary forms of interim protection when warranted (see Section II(A) of this Implementation Guide);

- the characteristics of an effective investigation, the need to consider any possible link between the crime and the journalist’s professional activities, gender-related issues and a possible link between racist attitudes and the act of violence, the need to exercise restraint in resorting to criminal proceedings/criminal sanctions for press offences, even when territorial integrity/national security are invoked (see Section III (A) of this Implementation Guide);

- the need to counter discriminatory or arbitrary application of defamation legislation, to prevent abuse of the judicial process and relevant measures, including best practices and to prevent forum shopping in defamation cases (see Section II (C) of this Implementation Guide);

- improving LEAs’ understanding of how to investigate threats and other criminal offenses that take place online, including those that are gendered. Training should highlight that online threats and harassment that amount to criminal offenses must be prosecuted and treated like offline offenses. Threats to life and physical integrity, including rape threats, should be prioritised for prosecution.

Involvement of non-state actors

- States should explore the potential of cooperation with NHRIs in training judges and prosecutors in order to avoid arbitrary application of restrictive legislation vis-à-vis journalists and other media actors.