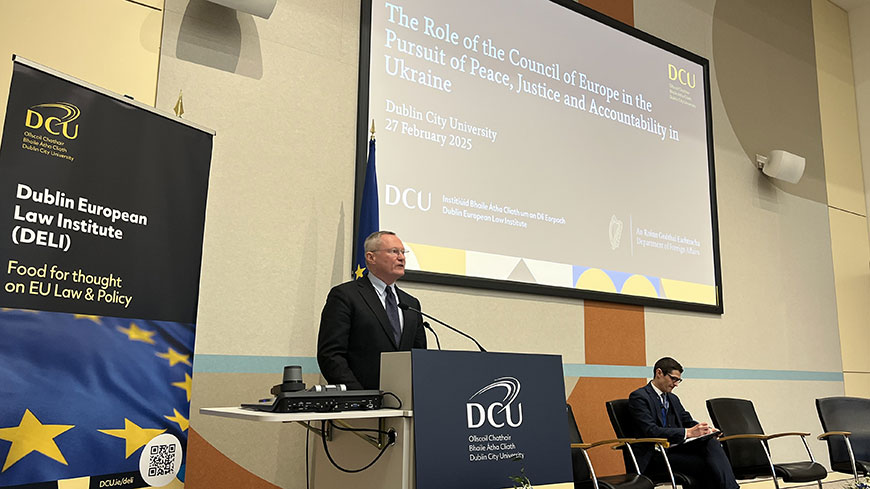

Speech delivered by Michael O’Flaherty at the conference “The Role of the Council of Europe in the Pursuit of Peace,

Justice and Accountability in Ukraine” organized by the Dublin European Law Institute in Dublin.

Good afternoon, thank you for that very warm introduction. Thank you and well done to DCU for the event. I join all those who are so impressed by everything we saw and heard this morning.

I consider this event to be an honorable exception. A very honorable exception in that there is a focus on people, on justice, on human well-being, on human rights throughout the discussions. That is honorable but sadly it is also exceptional.

There is no mention of human beings in what I'm following in the media from the current US initiatives. It's about property, it's about land and there is no reference to the people who live on that land or who have been displaced from that land.

Earlier this week with my colleagues we did a review of what the major influential US think tanks are saying recently about Ukraine. We found little about the specific issues of honoring human dignity in the context of building a peace.

References to human rights are also somewhat limited in other places where one looks for ideas and hope. The Bürgenstock summit of last year in Switzerland only narrowly refers to issues of human rights and then when you look at the operative paragraphs of the UN resolutions adopted this week, again here little attention.

This absence of attention to human rights makes it necessary to restate a few basics.

The first basic has to do with the scale of the human rights abuse that we're witnessing. According to the UN over 12,000 civilians dead, of whom 650 were children and so many countless military deaths in addition. 700 medical facilities and 1,500 schools damaged or destroyed. Summary executions, escalating rates of summary executions by Russian forces who also according to reports are torturing prisoners. A country, Ukraine, that is now littered with unexploded ordnance with all the consequences for years to come, and in the occupied territories a despotic regime.

The second fact that needs to be restated has to do with the perpetrator. Responsibility for the aggression and the consequent systematic and sustained violation of human rights lies with the Russian Federation.

Third, what kind of human rights abuses and violations are taking place? All categories. It is as much about the violation of economic, social and cultural rights as it is civil and political rights. Just consider the attacks on infrastructure and the deliberately inflicted environmental disasters and the impact they have for every imaginable human right.

Fourth of my cluster of facts has to do with the need for a persistent and full engagement with the situation in Ukraine on the part of regional and international human rights machineries. Our organisations could do still more in terms of adjusting working methods and deployment of resources in order to best support the people of Ukraine. In terms of my own mandate, I do consider that the situation of Ukraine is my top priority and I will visit the country again within the next couple of weeks.

Staying with the international mechanisms it is important to acknowledge the vital role that is being played by the United Nations in terms of monitoring. The UN has become the primary source in terms of reliable information on what is happening on the ground. I express my deep appreciation for the work of the UN Monitoring Mission and the UN Commission of Inquiry, whose task has been made all the harder with the refusal of Russian forces to give access to territory under its de-facto control.

Before I move on let me briefly engage the issue of why invest in monitoring. I started my international work in Bosnia-Herzegovina in the early 1990s, and in conflict after conflict, in Bosnia and subsequently, I've seen the critical role that an investment in monitoring plays. It is key to understanding and responding to the immediate situation. It also plays an important role towards eventual criminal justice and third, and no less significantly, it does or it should orient the path to peace.

It is the orientation of the path to peace that is my big preoccupation right now and it will be a focus of my attention including during my upcoming visit.

There is considerable global good practice in this area. Allow me to draw from this and identify ten points for a human rights roadmap towards a just, a fair, and a lasting, effective peace.

The first is about ensuring accountability, including criminal accountability. It is about supporting the International Criminal Court and moving towards the establishment of the tribunal on aggression. It is also essential to support national capacity. Whatever happens elsewhere, the vast majority of criminal processes towards justice will be at the national level. And so we should already now be intensifying our own engagement with Ukraine to support its capacity to do human rights compliant investigation, prosecution, and trials.

The second dimension has to do with the delivery of redress and restitution. And I very much welcome, and indeed I am proud to be associated with the Organisation that took the lead on such initiatives as the Register of damage, towards a claims commission, and so forth.

Third we have to remember that Ukraine is going to need a lot of help and support as it transitions out of martial law and towards a fully functioning democratic society.

Fourth, we must consider the challenges that will be faced within territories liberated by Ukraine, and indeed in territories that may not immediately be liberated.

Fifth, respect for human rights will need to be at the heart of all planning for the return of IDPs and refugees.

Sixth of my 10 points has to do with the release of prisoners. There will be complex human rights issues to navigate in terms of release of prisoners held on all sides, including those who may have been relocated to Russia. And let us never disregard those children who have been taken to Russia and all of the disappeared.

My seventh point relates to the reconstruction of a physically deeply damaged country. There is need right now for a humanitarian engagement that will continue into the near future, and that will transition into a more developmental or reconstruction phase. To ensure that this is focused on human dignity and well-being we need human rights to run through it like a golden thread.

The eighth point concerns the interplay of the EU accession pathway and the peace process. And of course, I'm looking at that from the particular point of view of human rights. The EU accession pathway will carry with it human rights obligations as also should any peace agreement. These two important sets of commitments will need to be aligned and cross-referenced.

Ninth of my 10 points has to do with that picture we all saw last week from Riyadh. From the first meeting of the Russians and the United States representatives. The telling thing about the picture was that it was all men. And I thought as I looked at that picture, what about UN Security Council resolution 1325? What about the vast experience in appreciating that you cannot have a good peace process without the participation of women.

10th and finally, I stay with the issue of actors.

Which actors should be in the room? It's about having women there. And Ukraine should sit at the head of the table. What is more, Ukrainian civil society can play an important role as can the very well regarded national human rights institution of the country.

And of course, we need representation of the relevant regional and international human rights bodies. And that brings me to an observation.

The human rights dimensions of peace will be better addressed if appropriate multilateral organisations are deeply engaged. In the particular context of Ukraine, I consider that the Council of Europe can play an essential and central role. I will support that endeavour as best I can.

The last point I wish to make has to do not with the human rights of Ukrainians, but all our human rights: the impact that the Russian aggression has for all of us and for all of our human rights. And here again, I'm concerned.

I'm concerned at the extent to which the aggression has triggered a diminution in respect for human rights in parts of other countries. I think of the securitisation of European borders. I think of the three cases in which I made interventions at the European Court of Human Rights last week regarding so-called pushbacks at the Belarusian border.

Another human rights dimension impacting all of us is the flood of disinformation and the spread of hate that is infecting our societies.

And then finally, in terms of the human rights impact beyond the borders of Ukraine, there is the existential threat to every one of us and every one of our societies if Russia were to succeed. The war is a war on values, it is a war on the fabric we have so carefully constructed since the Second World War. If Russia either wins or is perceived to win in its aggression, then our Europe will have been very badly damaged indeed.

And that is the context in which I express my deepest respect and acknowledge our profound debt to Ukraine. There is talk at the moment of Ukraine paying for security, of paying for interventions to help it overcome the aggressor. But Ukraine owes us nothing. It is we who owe Ukraine an undying debt of gratitude for being the ones willing to stand up to the tyrant.

Thank you.