Everyone in Europe - children, women and men - should be protected from forced labour and trafficking in human beings, two serious human rights violations. The latest International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimates indicate some 20.9 million people around the world still being subjected to forced labour, and 880,000 in the European Union. Among these victims, 90% are exploited in the private economy, by individuals or private companies. Within this group, 22% are victims of forced sexual exploitation and 68% of forced labour exploitation in economic activities, such as agriculture, construction, domestic work or manufacturing.

An overview of the country reports of the Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (GRETA) clearly shows that Europe is not immune to human trafficking and that certain groups, including women, children and minorities, are particularly vulnerable to this phenomenon. As illustrated by a study, the practice of human trafficking has a disproportionate impact on Roma, a group already suffering widespread discrimination and marginalisation.

The figures mentioned above, which are generally considered to be underestimates, are even more striking when we recall that slavery, servitude and human trafficking are clearly prohibited by international and European legal standards. Of particular relevance are Article 4 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) on the prohibition of slavery and forced labour, and the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (anti-trafficking Convention), which celebrated its 10th anniversary this year. The latter has now been ratified by 42 out of 47 member states of the Council of Europe –all but the Czech Republic, Liechtenstein, Monaco, the Russian Federation and Turkey - and by one non-member state, Belarus.

It is important to keep in mind some fundamental distinctions. Forced labour is any work or service which is exacted of someone under the menace of a penalty and for which that person has not offered him or herself voluntarily.

A victim of human trafficking is a person who has been recruited, transported, transferred, harboured or received within a country or across borders, by the use of threat, force, fraud, coercion or other illegal means, for the purpose of being exploited. Importantly, a child is considered to be a victim of human trafficking if he has been recruited, transported, transferred, harboured or received within a country or across borders for the purpose of being exploited, regardless of whether any of the aforementioned means were used.

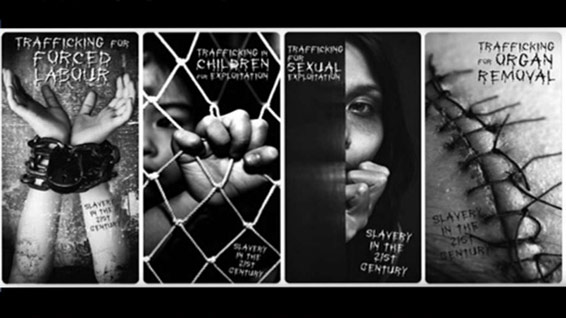

In the context of human trafficking, exploitation is to be understood broadly so as to include: sexual exploitation; forced labour or services; slavery or practices similar to slavery; servitude; the removal of organs.

To give some concrete examples, I was informed by the Austrian authorities that the most frequent human trafficking was for sexual exploitation, forced labour as well as slave-like situations of domestic workers of foreign diplomats. In Belgium, numerous cases of trafficking for labour exploitation have been documented, including the case of several Moroccan workers exploited by a construction company. In Italy and nearly all European countries, Nigerian women have been found to be trafficked for the purpose of prostitution.

Other widespread forms include cases of exploitation where children or persons with disabilities are forced to beg by traffickers. For instance, cases of trafficking of Roma children for forced begging were reported in France. Forced committing of petty offences is another emerging form of exploitation, as in the documented case of Vietnamese youths trafficked in the UK to work in cannabis farms.

A new international legally binding treaty to protect the rights of victims of forced labour

The 2014 Protocol to the 1930 ILO Forced Labour Convention provides victims of forced labour with similar rights as the Council of Europe Anti-Trafficking Convention establishes for victims of trafficking. The Protocol, which has so far only been ratified by Niger, requires that states parties take effective measures to prevent and eliminate the use of forced labour; provide protection and access to appropriate and effective remedies to victims, such as compensation, irrespective of legal status in the national territory; and sanction the perpetrators of forced or compulsory labour. All member states of the Council of Europe should swiftly ratify and fully implement this new instrument in addition to the anti-trafficking Convention

The importance of distinguishing human trafficking and people smuggling

Trafficking in human beings is very often closely linked with migration. Migrants, in particular when undocumented, are among the groups at high risk of exploitation. However, the smuggling of migrants and trafficking in human beings should not be confused.

While the aim of people smuggling is unlawful cross-border transport in order to obtain a financial or other material benefit, the purpose of trafficking in human beings is exploitation. Furthermore, trafficking in human beings does not necessarily involve crossing a border. For instance, In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the majority of victims of trafficking identified by the authorities were trafficked within the country.

Now more than ever, the terms “smuggling” and “trafficking” are employed interchangeably in relation to migrants crossing the Mediterranean sea or using the Western Balkan routes. Many states claim that they are taking measures against networks of “human traffickers” or even against “modern slavery” whereas such measures target in fact people smugglers. This discourse has been severely criticised by over 300 scholars from around the world as an attempt to “twist the 'lessons of history' to authorise unjustifiable violence”.

It is also important that measures taken against people smuggling do not have a negative impact on action against human trafficking. Referring to the humanitarian crisis in the Mediterranean region, GRETA recently called upon states parties to “ensure that migration policies and measures to combat migrant smuggling do not put at risk the lives and safety of trafficked people and do not prejudice the application of the protection and assistance measures provided by the anti-trafficking Convention”.

Clearly, military actions against boats used to transport smuggled migrants and the closing and militarising of borders should never be presented as solutions to the problem of human trafficking. On the contrary, in the absence of suitable legal migration solutions, these measures are likely to increase the vulnerability of those fleeing wars to exploitation by traffickers, including because they need to find money to pay smugglers for increasingly dangerous – and therefore expensive – ways to reach Europe. When it comes to preventing trafficking in a migratory context, the real solution is to open channels for legal (labour) migration and always protect the rights of migrants.

The need for a child-sensitive approach to combating forced labour and human trafficking

The economic crisis has had dire consequences on vulnerable groups, especially children. During my country visits, in particular to Spain and Portugal, I noted with concern that an increasing number of children are dropping out of school to find employment and support their families. This raises serious human rights issues, including the risk of the re-emergence of child labour, which hinders children's development, potentially leading to lifelong physical or psychological damage.

Children are often considered as perpetrators of petty crime by law enforcement officials, when they are in fact victims of exploitation by the real criminals. Child victims of trafficking should always be identified as such by law enforcement officials, prosecutors and judges. This means that one should look beyond appearances in the field of juvenile justice, in order to be able to apply the non-punishment provision of the anti-trafficking Convention (Article 26) to victims of trafficking who have been compelled to act illegally by their traffickers. Still, this is not sufficient. Child victims of trafficking should also receive adequate assistance tailored to their specific needs. In this respect, I find it disturbing that, as I witnessed in Bulgaria, some trafficked children are placed in juvenile justice institutions instead of being given the full assistance they need. In the current context of migration, it is also worrying to note, as in Denmark, reports of disappearances of children from accommodation centres for unaccompanied migrant children. This is not acceptable. Children without parental care who have been confronted with exploitation must be protected and receive all the support they require in full compliance with the UN Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children.

The need to involve all states and non-state actors in the action against forced labour and human trafficking

Exploiters and traffickers for the purposes of forced labour are mainly private persons (individuals or companies) exploiting other private persons. This means that the prevention of forced labour and trafficking should be geared at all parts of the supply chain in industries at high risk of exploitation, such as in the textile, agriculture or tourism sectors. National and transnational companies should be made accountable in case of human rights abuses, including through effective and appropriate penal sanctions, in line with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, regardless of whether exploitation takes place in Europe or in other parts of the world.

However, the European Court of Human Rights has made it very clear that states have a positive obligation under Article 4 of the ECHR to prevent forced labour and trafficking, to protect the victims and to prosecute the exploiters and traffickers. Member states of the Council of Europe should therefore live up to their crucial responsibility to respect, protect and fulfill the human rights of all victims - or persons at risk of becoming victims - of forced labour and human trafficking.

Nils Muižnieks