In 2017 in Bosnia and Herzegovina, a group of dedicated grassroots environmental activists staged a 500-day-long protest against the construction of new hydropower dams on the Kruščica river. The fight led by local women, who later came to be known as the Brave Women of Kruščica, met with many obstacles, including physical violence and arrests, but it has not been in vain: it has helped to safeguard access to fresh drinking water for local residents while staving off risks posed by the projects to the habitat of many animal species.

Two years later, in 2019 in the United Kingdom, more than ten years of protests and pressure from environmental campaigners resulted in a government moratorium on fracking, a controversial method of extracting underground gas, offering relief to residents of areas located near extraction sites who feared earth tremors and exposure to other environmental harms linked to potential accidents.

In Spain, almost twenty years of relentless campaigning and a legal battle by Spanish ecologists culminated in October 2020 in victory when the country’s Supreme Court issued a ruling that put an end to a vast residential development project threatening a coastal natural park recognised for its protected marine habitats.

And in March 2021 in France, a government decree setting very short buffer distances between human habitat and areas treated with highly toxic pesticides was deemed unconstitutional thanks to the collective efforts of a number of national and regional environmental NGOs, backed by citizen and consumer associations and health organisations.

These are just a handful of real-life examples of how environmental action has benefited the human rights and collective safety of entire communities in Europe. Many other inspiring success stories can be found, including on Voices of Nature, a brand new website set up by the Council of Europe’s Bern Convention. There are countless others around the world. Some make the headlines. Many go unnoticed.

Environmental human rights defenders

The people behind these extremely important efforts are environmental human rights defenders. The term refers to human rights defenders working on environmental issues. Many of them are ordinary citizens who are simply exercising their human rights, or who are forced to act by circumstances or sheer necessity; some of them may fall into this category regardless of whether or not they self-identify as human rights defenders. The interdependence between human rights and the environment has gradually become one of the central pillars of today’s human rights discourse, as I have noted in my 2019 human rights comment entitled “Living in a clean environment: a neglected human rights concern for all of us”. It is now abundantly clear that environmental harm interferes with the enjoyment of basic human rights and freedoms, such as the right to life, to health, to privacy, or freedom from inhuman or degrading treatment. It follows from this that those who act to protect the environment and to prevent environmental degradation, including climate change, contribute to the protection of our human rights.

The critical contribution made by environmental human rights defenders to our societies has not gone unrecognised, as evidenced by, for example, the landmark resolution on environmental human rights defenders adopted in 2019 by the Human Rights Council, and the “Geneva Roadmap” that seeks to aid its effective implementation. Their role has also been acknowledged by the mandate of the United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment, not least in the seminal UN Framework Principles on human rights and the environment. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), together with the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Universal Rights Group, have developed a dedicated resource portal and a Defenders Policy in support of environmental defenders. Within the Council of Europe, this year’s 9th Edition of the World Forum for Democracy honours their work by focusing on the topic “Defending the Defenders” as part of its year-long campaign devoted to the complex interplay of democracy and environmental protection. In many places around Europe, national and local authorities have given environmental human rights defenders a seat at the policy table in recognition of their valuable voice, experience, and expertise.

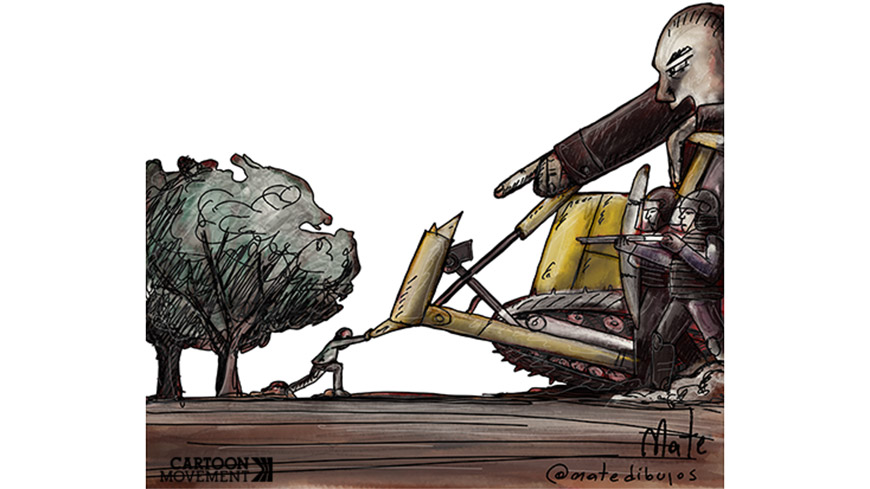

At the same time, governments in Europe often consider environmental defenders and environmental advocacy a nuisance at best, and a threat at worst, and respond to legitimate activism with reprisals. Some simply allow unbridled economic development to take precedence over citizens’ legitimate environmental concerns or allow vested moneyed interests and powerful non-state actors to stifle activism. Environmental defenders’ activities have won them some formidable enemies and in many places around Europe today, speaking out and standing up for the environment or denouncing the effects of climate change carries a hefty price tag.

A rise in attacks and reprisals against environmental defenders

The persecution of environmental human rights defenders in Europe is hardly a new phenomenon. In the 2014 report entitled “A Dangerous Shade of Green”, the NGO ‘Article 19’ documented dozens of examples of killings and violent attacks on environmental activists on the continent; other examples, mostly from countries of the former Soviet Union, can be found in the 2019 report “Dangerous work: Reprisals against environmental activists” by the NGO Crude Accountability. Sadly, however, these attacks and incidents have not abated – if anything, they have grown in intensity. Only recently, over 400 academics researching climate and environmental change published an open letter in which they voiced concern about the increasing criminalisation and silencing of environmental activists around the world, which they see as “a new form of anti-democratic refusal to act on climate.”

Support for the work of human rights defenders, their protection, and the development of an enabling environment for their activities are among the core elements of my mandate as Commissioner for Human Rights. It was with this in mind that last December I convened an online roundtable with environmental human rights defenders from across Europe, including lawyers, campaigners and representatives of both local and international NGOs from several European countries. Their testimonials have laid bare the intensification of oppression and intimidation faced by Europe’s environmental human rights defenders in recent years. As can be seen in the conclusions of the roundtable report, those who bring truth to light on environmental issues and are at the forefront of the fight against climate change are currently facing attacks on all fronts.

Sadly, there are places in Europe today where environmental human rights defenders are beaten, threatened, verbally abused, intimidated, or otherwise prevented from carrying out their legitimate activities in a safe and free manner. To mention but a handful of the most glaring examples: an environmental campaigner from Russia was severely beaten by unknown assailants and hospitalised with skull fractures and a broken nose. In Ukraine, an environmental activist investigating the pollution of a local river, allegedly caused by a nearby waste treatment plant, was found hanged under suspicious circumstances. The fight against illegal logging in Romania’s primeval forests has already claimed the lives of several rangers and has put the lives of some activists at risk. I personally heard the harrowing testimony of an environmental campaigner who described being beaten almost to death in 2015; although his assailants were caught on video and identified by an eyewitness, they have never been brought to justice.

When confronted with reports of violence or intimidation of environmental human rights defenders, law enforcement agencies all too often turn a blind eye. Worryingly, in some European countries, this has become quite commonplace. Government reprisals or the inability or unwillingness of public authorities to guarantee the safety and protection of environmental activists has led some of them to seek refuge elsewhere. A prominent environmental activist and head of one of Russia’s oldest environmental groups had to flee the country after being harassed with numerous spurious judicial proceedings. Several other environmental campaigners who fought against the construction of a motorway through a primeval forest, opposed the illegal exploitation of protected forestland, or advocated more openness about the fallout of a nuclear incident, had to leave Russia out of concern for their own and their families’ safety. An environmental defender from Romania told me about having to relocate abroad after receiving information about a bounty placed on his head by criminals in connection with his environmental work, fearing the law enforcement’s inability to guarantee his protection.

Stigmatisation, surveillance and other restrictions on environmental activism

Violent attacks are hardly the only problem facing environmental defenders today, however. Increasingly, governments view and present environmental organisations as suspicious and pass legislation or measures with the aim of limiting their scope for action. A prime example of such legislation disproportionately affecting legitimate environmental activism are the so-called foreign agent-type laws. Such laws force many environmental defender organisations to either avoid official registration altogether or to discontinue their operations, on pain of heavy fines and other punitive measures, including criminal prosecution, judicial harassment, or dissolution. The first such law, adopted by Russia in 2012, was the subject of my predecessor’s intervention in a case pending before the European Court of Human Rights. Regrettably, this bad example has inspired copycat solutions in other parts of Europe. Similar legislation was adopted in Hungary in 2017 despite criticism from my office – and found to be in breach of EU law in June 2020. In May 2020, Poland’s environment minister announced that similar legislation was under consideration and that a working group had been set up to that end; he also accused some environmental organisations of acting not for the environment’s sake but rather on the instructions of undefined “bigger interests”. In Slovenia, the government inserted in a bill on COVID-19-related economic support a provision limiting the ability of environmental activists to participate in environmental impact assessments; the proposal is currently under constitutional review.

Environmental human rights defenders who took part in the above-mentioned roundtable mentioned various other types of government activities deliberately limiting their scope for action and effectively hampering collective efforts to put an end to the adverse consequences of environmental degradation and climate change. These, in turn, can have a chilling effect on the whole of society. In many Council of Europe member states, environmental human rights defenders are deliberately mocked, ridiculed, scapegoated, marginalised, or even likened to extremists and given derogatory labels, such as ‘(eco-)terrorists’ – including by public officials, media outlets, or even judicial authorities. Some governments and businesses resort to offensive and stigmatising public relations campaigns to isolate environmental campaigners and make attacks on them more justifiable to the general public. Their organisations are also smeared online in an attempt to tarnish their reputation, and activists are regularly cyber-bullied. In some member states, law enforcement agencies disrupt the legitimate activities of environmental organisations by raiding their offices and seizing their equipment, thereby further adding to the stigmatisation in the public eye.

Worryingly, participation in environmental protests is also increasingly equated with unlawful activity or interpreted as a ground for imposing preventive individual restrictions on freedom of movement or the right to liberty. Rules on public assemblies are sometimes applied selectively to the detriment of protests by environmental groups. Public participation in global environmental summits has often been curtailed and large numbers of environmental activists placed under surveillance. These last measures in particular represent a far-reaching intrusion into the privacy of those targeted, but are difficult to detect and challenge legally, due to their covert nature.

For example, ahead of the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) in 2015, France imposed surveillance measures on a number of grassroots environmental activists and placed some of them under preventive house arrest. Legislation adopted by Poland ahead of the COP24 conference in 2018 gave broad surveillance powers to the police and secret services to collect personal data about COP24 participants and to prevent spontaneous peaceful assemblies in the city where the summit was being held. In 2019, a court in Moscow sentenced a youth climate activist and solo picketer to six days in detention for his peaceful protest as part of the global “Fridays for the Future” campaign. In the United Kingdom, the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill – currently before Parliament – has been criticised by environmental activists for its possible negative impact on freedom of assembly and peaceful protests, and for the discouraging effect its provisions would have on people’s participation in environmental demonstrations.

Intimidation and harassment of environmental journalists

Aggressive tactics used against environmental human rights defenders are also frequently extended to investigative journalists, both because of the environmental harm they might uncover and due to their role in helping activists spread the message about their causes. Examples mentioned during the roundtable ranged from a vexatious lawsuit by an oil company against a newspaper to testimonies about threats against journalists interested in covering environmental campaigns. In March this year, in an apparent attempt to cause a road accident, two bolts were removed from the wheel of a car belonging to a French investigative journalist known for her investigations into the agricultural sector; this incident followed previous threats to her and her family and the poisoning of her dog. Another freelance journalist renowned for her investigation into the environmental degradation caused by the discharge of toxic pesticides by the agri-food industry was targeted by groundless defamation lawsuits initiated by powerful business owners. Although these claims were eventually withdrawn, the overall objective of such vexatious lawsuits, otherwise known as “strategic lawsuits against public participation” (SLAPPs), is to intimidate journalists into abandoning their environmental investigations.

The way forward

The worrying state of affairs described above is untenable. If European governments – both at the central and the local level – are serious about their stated commitments to fighting environmental pollution and climate change, it is high time that they recognised and acted decisively on their responsibilities vis-à-vis environmental human rights defenders and environmental journalists.

First of all, Council of Europe member states must provide a safe and enabling environment for environmental human rights defenders to operate free from violence, intimidation, harassment, or threats. They should adopt a zero-tolerance policy on human rights violations against environmental human rights defenders and environmental journalists; swiftly and firmly condemn any threats or violence against them and their organisations – including by non-state actors; lead full and effective investigations into any threats or violence committed against them, with a view to bringing the perpetrators to justice; and provide access to effective remedies for such violations.

Second, we must put an end to the stigmatisation of environmental human rights defenders in Europe, including that emanating from non-state actors and taking place online. Politicians and opinion leaders must refrain from referring to environmental defenders using derogatory terms and from seeking to misrepresent or undermine their work. Instead, they should publicly and firmly support their activities and recognise the fundamental importance of their engagement and their contribution to our societies. They should also repeal legislation that interferes with environmental organisations’ ability to work freely and independently. There can be no room in Europe for foreign agent-type or other laws stifling legitimate civil society activism.

Third, public protests and campaigns are among the most effective -- and indeed indispensable -- environmental advocacy tools for raising public awareness and effecting change. States should respect freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly in relation to environmental matters, and protect the exercise of these rights from interference, including from non-state actors.

Fourth, we must pay due heed to the voice of environmental human rights defenders. Public authorities and private businesses should ensure genuine, effective, and transparent participation of environmental organisations, communities and individuals in decision-making on all policies and projects which may have an environmental impact. States should collect and disseminate environmental information and guarantee procedures that allow concerned individuals to act when confronted with environmental degradation, including the right to receive affordable, effective and timely access to information about environmental issues. In line with my recent written observations to the European Court of Human Rights in a case concerning the negative impact of climate change on human rights, states should also ensure respect for the right to a remedy and remove barriers to access to justice by victims of human rights violations caused by environmental degradation or climate change.

In this regard, I reiterate my call for all Council of Europe member states that have not yet done so to promptly ratify the 1998 Aarhus Convention and the 2010 Council of Europe Convention on Access to Official Documents (Tromsø Convention) and to support their effective implementation. I also invite those states that have already ratified the Aarhus Convention to consider supporting the development of a rapid response mechanism in order to deal with cases of harassment and threats against environmental human rights defenders.

Respect for the rights of environmental human rights defenders is also an obligation of non-state actors. Businesses in Europe should internalise their corporate responsibility to respect human rights, in line with the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework. Against the backdrop of the ongoing push for more stringent rules on corporate due diligence on human rights in Europe, it is now more than ever important for companies to be seen as positive and responsible players, in particular with regard to environmental human rights and those who defend them.

Lastly, Europe needs more environmental human rights defenders. States should strive to ensure public awareness on environmental matters and to educate people from an early age about the need to preserve the environment and how to do so. I was pleased to learn that in Sweden and Finland, for instance, lessons on the environment and its meaning for individuals and societies are integrated in school curricula, at every stage of education. Such initiatives are essential for raising a new generation of environmentally aware and active citizens. The Council of Europe offers valuable educational resources in this area.

We cannot claim to be serious about protecting the environment or combating climate change unless we protect those who put themselves on the line for these goals. I want to pay tribute to the environmental human rights defenders’ selfless work and the sacrifices they make so that we can have a dignified future existence on this planet. Without their vision and courage, the environment we live in is bound to suffer serious harm – along with our human rights and well-being. Defending the defenders is not just a moral and political imperative. At the very least, it should also be a reflex for collective self-preservation.

I will continue to raise concerns regarding the plight of environmental human rights defenders in dialogue with authorities and to speak out whenever they face attacks, reprisals, or undue restrictions. I would also appeal to everyone to stand firm in their defence. As they are increasingly targeted, let us reverse the trend and make Europe a safe place for environmental activism.

Dunja Mijatović