Il Corriere della Sera, 08/06/2014

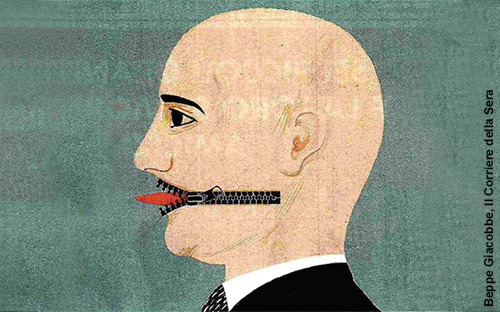

When Parliament started reviewing the legislation on defamation last October, there were great hopes that Italy finally would succeed in carrying out a long overdue legal reform and strengthening media freedom in the country. Regrettably eight months later, the new draft law still falls short of both national and international standards and the whole reform process appears to be stuck in the Senate. The current version of the draft still includes the possibility to file penal suits for defamation, increases monetary fines and lacks effective deterrent measures to prevent the abuse of the law by the plaintiffs.

The current legal framework criminalising defamation has led to Italy losing court cases in international tribunals and receiving repeated criticism, especially because of prison sentences handed down to journalists. Already in 1984, this anomaly was exposed by the Italian Court of Cassation. Since then, Italy has been regularly condemned by the Strasbourg Court for violating the right to freedom of expression enshrined in the European Convention on Human Rights because of disproportionate criminal sanctions in defamation cases.

Meanwhile the instrumental use of defamation suits and claims for damages continues to hamper media freedom in Italy, as documented by the long list of journalists targeted by spurious legal actions published by Ossigeno per l’Informazione, an observatory which carries out valuable awareness raising work on threats against journalists in the country.

We, our predecessors and other bodies of the Council of Europe, OSCE and the United Nations, have called on the Italian authorities for decades to reform anachronistic legislation which stifles criticism and muzzles the media toward a modern set of provisions which would strengthen free expression by removing prison sentences and excessive fines.

If the latest draft law adopts some of our recommendations, above all the removal of the prison sentence for defamation, other elements remain a source of serious concern, particularly those which have been mentioned earlier. These concerns could have already been dispelled if some amendments which had been proposed to improve the draft law had not been met by a negative opinion by the rapporteur, who was also backed by the Government.

But not everything is lost. Italy can still reverse a situation which puts it in breach of agreed international human rights standards, including those established by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. The best way to achieve this would be to stop considering defamation as a criminal offence altogether.

Freedom of expression, and its corollary of media freedom, is a human right that does not exist by chance; it is the result of lessons learned from the past on how to strengthen democracy. In particular free media helps protect the rule of law and is a key source of information necessary for citizens’ effective participation in a democratic society. It also sustains democracy by helping protect a variety of human rights. Instances of torture, discrimination, corruption or misuse of power have many times come to light because of the courageous work of journalists. Truth-telling is often the first, essential step to start redressing human rights violations and hold governments accountable.

However, as long as defamation is considered a crime and journalists can be threatened with disproportionate sanctions and fines, a chilling effect risks limiting the exercise of freedom of expression. This situation does not only stifle the media, but ultimately deprives citizens of their right to information, thus affecting negatively the healthy functioning of democracy.

We therefore call on the Italian Senate to amend the draft law on defamation. To better reflect both national and international standards, a new law should be designed around three main sustaining principles. First of all, defamation should be fully decriminalised. The mere existence of laws which criminalise the offense to the reputation of a person results in undesirable forms of self-censorship.

Second, the law should allow for corrections and apologies as remedies. In case civil sanctions are necessary, they have to be proportionate. Excessive and disproportionate damages awarded in civil defamation cases can exert heavy pressure on the offender, whose economic survival can be threatened in some cases.

Third, stronger deterrent provisions should be introduced to avoid the abuse of defamation law by the plaintiffs. This safeguard is necessary to ensure that the overall balance of the law and of its implementation is in favor of media freedom and freedom of expression.

Apart from these legal measures, a cultural change is also needed. International standards require policy and opinion makers, as well as public personalities, to accept a higher degree of public criticism and scrutiny, refraining from violent or intimidating reactions. This is crucial to help media operate freely.

Only a minority of the European countries have officially fully decriminalised speech offences. By upgrading its legislation on freedom of expression Italy can lead the way in the battle to decriminalise defamation. It is an opportunity that cannot be missed. Fully overhauling the legal framework on defamation is an essential step to sustain the country’s democratic fabric.

Frank La Rue, UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression

Dunja Mijatović, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media

Nils Muižnieks, Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights