Citizenship and Participation

What is citizenship?

Traditions and approaches to citizenship vary throughout history and across the world according to different countries, histories, societies, cultures and ideologies, resulting in many different understandings of the concept of citizenship.

The origin of citizenship can be traced back to Ancient Greece, when "citizens" were those who had a legal right to participate in the affairs of the state. However, by no means was everyone a citizen: slaves, peasants, women or resident foreigners were mere subjects. For those who did have the privileged status of being citizens, the idea of "civic virtue" or being a "good" citizen was an important part of the concept, since participation was not considered only a right but also, and first of all, a duty. A citizen who did not meet his responsibilities was considered socially disruptive.

Citizenship is a complex and multi-dimensional reality which needs to be set in its political and historical context… . Democratic citizenship, specifically, refers to the active participation by individuals in the system of rights and responsibilities which is the lot of citizens in democratic societies.

Consultation Meeting for the Education for Democratic Citizenship Programme of the Council of Europe, 1996

This concept of citizenship is reflected in today's most common understanding of citizenship as well, which relates to a legal relationship between the individual and the state. Most people in the world are legal citizens of one or another nation state, and this entitles them to certain privileges or rights. Being a citizen also imposes certain duties in terms of what the state expects from individuals under its jurisdiction. Thus, citizens fulfil certain obligations to their state and in return they may expect protection of their vital interests.

However, the concept of citizenship has far more layers of meaning than legal citizenship. Nowadays "citizenship" is much more than a legal construction and relates – amongst other things – to one's personal sense of belonging, for instance the sense of belonging to a community which you can shape and influence directly.

Such a community can be defined through a variety of elements, for example a shared moral code, an identical set of rights and obligations, loyalty to a commonly owned civilisation, or a sense of identity. In the geographical sense, "community" is usually defined at two main levels, differentiating between the local community, in which the person lives, and the state, to which the person belongs.

In the relationship between the individual and society we can distinguish four dimensions which correlate with the four subsystems which one may recognise in a society, and which are essential for its existence: the political / legal dimension, the social dimension, the cultural dimension and the economic dimension.1

The political dimension of citizenship refers to political rights and responsibilities

The social dimension of citizenship has to do with the behaviour between individuals in a society and requires some measure of loyalty and solidarity. Social skills and the knowledge of social relations in society are necessary for the development of this dimension.

The cultural dimension of citizenship refers to the consciousness of a common cultural heritage. This cultural dimension should be developed through the knowledge of cultural heritage, and of history and basic skills (language competence, reading and writing).

The economic dimension of citizenship concerns the relationship between an individual and the labour and consumer market. It implies the right to work and to a minimum subsistence level. Economic skills (for job-related and other economic activities) and vocational training pl

These four dimensions of citizenship are attained through socialisation processes which take place at school, in families, civic organisations, political parties, as well as through associations, mass media, the neighbourhood and peer groups.

As with the four legs of a chair, each person should be able to exercise the four dimensions in a balanced and equal manner, otherwise full citizenship will be unbalanced.

Question: What senses of belonging do you recognise in yourself?

When we are part of a community, we can influence it, participate in its development and contribute to its well-being. Therefore, citizenship is also understood as a practice – the practice of playing an active role in our society. Such participation might be within our neighbourhood, in a formal or informal social group, in our country, or in the whole world. The notion of active citizenship implies working towards the betterment of one's community through participation to improve life for all members of the community. Democratic citizenship is a closely related concept, which emphasises the belief that citizenship should be based on democratic principles and values such as pluralism, respect for human dignity and the rule of law.

Question: Would you consider yourself an active citizen?

Citizenship, participation and human rights

Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.

UDHR, article 27

Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognises the right to a nationality, a right to change one's nationality, and the right not to be deprived of nationality. The right to a nationality is confirmed in many other international instruments, including the European Convention on Nationality of the Council of Europe (1997). In the context of international norms, "nationality" and "citizenship" are usually used synonymously. This is true also for the Convention as underlined in its Explanatory Report4: nationality "…refers to a specific legal relationship between an individual and a State which is recognised by that State. …with regard to the effects of the Convention, the terms "nationality" and "citizenship" are synonymous".

The right to a nationality is extremely important because of its implications for the daily lives of individuals in every country. Being a recognised citizen of a country has many legal benefits, which may include – depending on the country – the rights to vote, to hold public office, to social security, to health services, to public education, to permanent residency, to own land, or to engage in employment, amongst others.

Although each country can determine who its nationals and citizens are, and what rights and obligations they have, international human rights instruments pose some limitations on state sovereignty over citizenship regulation. Specifically, the universal human rights principle of non-discrimination and the principle that statelessness should be avoided constrain state discretion on citizenship.

Participation, in political and cultural life, is a fundamental human right recognised in a number of international human rights treaties, starting with Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which provides for the right to participate in government and free elections, the right to participate in the cultural life of the community, the right to peaceful assembly and association, and the right to join trade unions. Participation is also a core principle of human rights and is also a condition for effective democratic citizenship for all people.

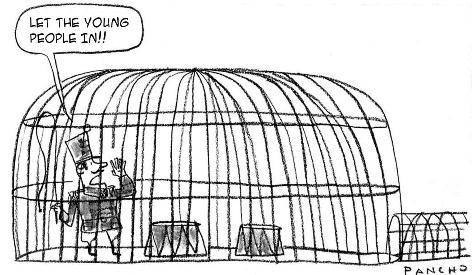

Participation is one of the guiding principles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. This treaty says that children (all people below the age of eighteen years) have the right to have their voice heard when adults are making decisions that affect them, and their views should be given due weight in accordance with the child's age and maturity. They have the right to express themselves freely and to receive and share information. The Convention recognises the potential of children to influence decision making relevant to them, to share views and, thus, to participate as citizens and actors of change.

Without the full spectrum of human rights, participation becomes difficult if not impossible to access. Poor health, low levels of education, restrictions on freedom of expression, poverty, and so on, all impact on our ability to take part in the processes and structures which affect us and our rights. Equally, without participation, many human rights are difficult to access. It is participation through which we can build a society based on human rights, develop social cohesion, make our voice heard to influence decision makers, achieve change, and eventually be the subject and not the object of our own lives.

Question: What forms of involvement or participation, other than voting in elections, are possible for the ordinary citizen?

Exercising citizenship

Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives.

UDHR, article 21

Much discussion concerning citizenship is focused on the problem of increasing citizens' involvement and participation in the processes of democratic society. It is being increasingly realised that periodic voting by citizens is insufficient, either in terms of making those who govern in the interim period fully accountable or in promoting feelings of empowerment among ordinary citizens. Furthermore, low voting turnouts indicate levels of political apathy among the population, which seriously undermines the effective functioning of democracy.

Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association.

UDHR, article 20

A second set of issues concerns the question of those individuals who do not, for one reason or another, receive the full benefits of citizenship. One aspect of this is a result of continuing patterns of discrimination within societies: minority groups may very often have formal citizenship of the country in which they are living but may still be prevented from full participation in that society.

A second aspect of the problem is a consequence of increasing globalisation, including new patterns of work and migration, which leads to a significant number of people throughout the world being resident abroad but unable to apply for formal citizenship. Such people may include immigrant workers, refugees, temporary residents or even those who have decided to set up permanent residence in another country.

Question: Should immigrant workers be entitled to some of the benefits of citizenship, if not to formal citizenship?

An estimated 70,000–80,000 Roma are stateless across5 Europe.

A third aspect is the issue of statelessness. Although the right to a nationality is a human right guaranteed by international human rights law, there are millions of people worldwide who are not nationals of any country. The UNHCR, the United Nations' refugee agency, estimates that there were 12 million stateless people at the end of 2010. Statelessness is often the result of the break-up of countries such as the Soviet Union or Yugoslavia, but stateless people may also include displaced persons, expelled migrants, and those whose birth has not been registered with the authorities.

The idea of citizen participation is a little like eating spinach: noone is against it in principle because it is good for you.6

Sherry R. Arnstein

Forms of participation

Participation of the citizens in their government is thought to be the cornerstone of democracy, and it can take place through different mechanisms and forms, and at various levels. Several models of participation have been developed, the earliest and probably the most well-known being Sherry Arnstein's ladder of participation (1969).

Arnstein identified eight levels of participation, each corresponding to one rung of the ladder, with little or no citizen participation at one end to a fully citizen-led form at the other. The higher you are on the ladder, the more power you have in determining the outcome. The bottom two rungs – manipulation and therapy – are not participative and should be avoided. The next three up – informing, consultation and placation – are tokenistic; they allow citizens to have a voice and be heard, but their views may not be properly considered by those in power. The final three steps – partnership, delegated power and citizen control – constitute real citizen power and the fullest form of citizen participation.

Rights versus reality

Roma communities are routinely discriminated against in many parts of Europe. In some cases, Roma are denied citizenship of the countries in which they live. When Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia broke up in the 1990s, some Roma were left without nationality because the successor states regarded them as belonging elsewhere, and implemented legislation that denied them citizenship. Furthermore, Roma parents who are stateless or have migrated to another country often fail to have their children registered, even though such children are entitled to citizenship under international law. As a consequence, such children cannot access some of their fundamental rights such as health care or education. Other communities with itinerant lifestyles, for example the Travellers in Britain, may face similar problems.

Even when Roma are formally recognised as citizens they may be excluded from fully participating in their communities and treated in practice like second-class citizens, due to widespread discrimination and prejudice.

States Parties recognize the rights of the child to freedom of association and to freedom of peaceful assembly.

Convention on the Rights of the Child

Arnstein's model was further developed by Roger Hart and adapted to the issue of children and youth participation. Hart stated that participation is a fundamental right of citizenship7, because this is the way to learn what being a citizen means and how to be one. Youth participation can also be seen as a form of a youth-adult partnership. There are different degrees to which youth can be involved or take over the responsibility, depending on the local situation, resources, needs and level of experience. Hart's ladder of participation illustrates different degrees of involvement of children and young people in projects, organisations or communities. These are the eight levels of youth involvement:

The earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens.

Baha'ullah

Rung 8: Shared decision making

Projects or ideas are initiated by young people, who invite the adults to take part in the

decision-making process as partners.

Rung 7: Young-people led and initiated

Projects or ideas are initiated and directed by young people; the adults might be invited to provide necessary support, but a project can be carried out without their intervention.

Rung 6: Adult initiated, shared decisions with young people

Projects are initiated by adults but young people are invited to share the decision-making power and responsibilities as equal partners.

Rung 5: Young people consulted and informed

Projects are initiated and run by adults, but young people provide advice and suggestions and are informed as to how these suggestions contribute to the final decisions or results.

Rung 4: Young people assigned but informed

Projects are initiated and run by adults; young people are invited to take some specific roles or tasks within the project, but they are aware of what influence they have in reality.

Participation means to be involved, to have tasks and to share and take over responsibility. It means to have access and to be included.

Peter Lauritzen3

Rung 3: Tokenism

Young people are given some roles within projects but they have no real influence on any decisions. There is a false appearance created (on purpose or unintentionally) that young people participate, when in fact they do not have any choice about what is being done and how.

Rung 2: Decoration

Young people are needed in the project to represent youth as an underprivileged group. They have no meaningful role (except from being present) and, as with decorations, they are put in a visible position within a project or organisation, so that they can be easy for outsiders to spot.

There are many ways in which young people play an active role as citizens of their societies. In 2011, a survey of young people aged between 15 and 30 living in EU member states was conducted to find out how young EU citizens are participating in society. It focused on their participation in organisations (e.g. sports clubs, voluntary organisations), political elections, voluntary activities and projects fostering co-operation with young people in other countries.Rung 1: Manipulation

Young people are invited to take part in the project, but they have no real influence on decisions and the outcomes. In fact, their presence is used to achieve some other goals, such as winning local elections, creating a better picture of an institution or securing some extra funds from institutions supporting youth participation.

The findings included the following:

- Across all countries, a minority of young people said they had been involved in activities aimed at fostering co-operation with young people from other countries; this ranged from 4% in Italy to 16% in Austria.

- About a quarter of young adults had been involved in an organised voluntary activity in 2010. The highest rates were observed in Slovenia, Denmark, Ireland and the Netherlands (36%-40%).

- Among young people who were old enough to vote, roughly 8 in 10 said that they had voted in a political election at the local, regional, national or EU level in the previous three years. This ranged from 67% in Luxembourg to 93% in Belgium (where voting is compulsory).

- Roughly a third of young people in the EU had been active in a sports club in 2010. About a sixth had been involved in a youth organisation and one in seven had participated in a cultural organisation's activities.8

Question: How can you make your voice heard in your youth group, organisation or school?

Youth participation in the Council of Europe

The aim of the Council of Europe's youth policy is to provide young people - girls and boys, young women and young men - with equal opportunities and experience which enable them to develop the knowledge, skills and competencies to play a full part in all aspects of society.9

The Council of Europe plays a major role in supporting and encouraging participation and active citizenship. Participation is central to the Council's youth policy in various ways:

Participation and active citizenship is about having the right, the means, the space and the opportunity and, where necessary, the support to participate in and influence decisions and engage in actions and activities so as to contribute to building a better society.

Revised European Charter on the Participation of Young People in Local and Regional Life

- Youth policies should promote the participation of young people in the various spheres of society, especially those that are most directly relevant to them. This includes support for youth organisations, setting youth platforms or consultative bodies, recognising the role of students' councils and students' unions in the management of schools, and so on.

- Youth policies should be developed, implemented and evaluated with young people, namely through ways that take into account the priorities, perspectives and interests of young people and involve them in the process. This may be done through youth councils and fora (national, regional or local) or/and through other ways of consulting young people, including forms of e-participation.

- Youth policies and programmes should encourage participant-centred approaches to learning and action, such as in human rights education, through which participants exert and learn participation and citizenship.

These dimensions of youth participation reflect the approaches of the Revised European Charter on the Participation of Young People in Local and Regional Life, which stresses that:

to participate means having influence on and responsibility for decisions and actions that affect the lives of young people or are simply important to them. In practice, therefore, this could mean voting in local elections as well as setting up a youth organisation or an Internet forum to exchange information about hobbies and interests or other cre

The European Charter on the Participation of Young People in Local and Regional Life11 (produced in 1992 and revised in 2003) is an international policy document approved by the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of the Council of Europe. The Charter consists of three parts relating to different aspects of youth participation at a local level. The first provides local and regional authorities with guidelines on how to conduct policies affecting young people in a number of areas. The second part provides the tools for furthering the participation of young people. Finally, the third section provides advice on how to provide institutional conditions for the participation of young people.

Have your Say! is the Council of Europe's Manual on the Revised European Charter on the Participation of Young People in Local and Regional Life12 , available online in 11 languages.

The charter outlines 14 areas in which young people should be involved. They are the following:

1. sport, leisure and associative life

2. work and employment

3. housing and transport

4. education and training

5. mobility and intercultural exchanges

6. health

7. equality for women and men

8. young people in rural areas

9. access to culture

10. sustainable development and environment

11. violence and crime

12. anti-discrimination

13. love and sexuality

14. access to rights and law.

In a unique manner to implement youth participation in youth policy, the Council of Europe has introduced a co-management system into its youth sector, where representatives of European non-governmental youth organisations and government officials work together to develop priorities for and make recommendations concerning youth. This co-management system consists of three bodies: the European Steering Committee for Youth, the Advisory Council on Youth and the Joint Council on Youth.

The Advisory Council is made up of 30 representatives from youth NGOs and networks, who provide opinions and input on all youth sector activities. It has the task of for¬ mulating opinions and proposals on any question concerning youth, within the scope of the Council of Europe.

The European Steering Committee for Youth (CDEJ) consists of representatives of ministries and organisations responsible for youth matters from the states parties to the European Cultural Convention. It encourages closer co-operation between governments on youth issues and provides a forum for comparing national youth policies, exchanging best practices and drafting standard texts. The CDEJ also organises the Conferences of European Ministers with responsibility for youth matters and drafts youth policy laws and regulations in member states.

The Joint Council on Youth brings the CDEJ and the Advisory Council together in a co-decision body, which establishes the youth sector's priorities, objectives and budgets.

The European Youth Forum

The European Youth Forum is an independent, democratic, youth-led platform, representing over 90 national youth councils and international youth organisations from across Europe. The Youth Forum works to em-power young people to participate actively in society to improve their own lives, by representing and advocating their needs and interests and those of their organisations.13

Endnotes

1 These four dimensions of Citizenship were developed by Ruud Veldhuis, in "Education for Democratic Citizenship: Dimensions of Citizenship, Core Competencies, Variables and International Activities", Strasbourg, Council of Europe, 1997, document DECS/CIT (97) 23, quoted here from T-Kit 7 – Under Construction, T-Kit on European Citizenship, Council of Europe and European Commission, Strasbourg, 2003

2 T-Kit 7 – Under Construction, T-Kit on European Citizenship, Council of Europe and European Commission, Strasbourg, 2003

3 Peter Lauritzen, keynote speech on participation presented at the training course on the development of and implementation of participation projects at local and regional level, European Youth Centre, June 2006

4 Explanatory Report to the European Convention on Nationality, Article 2, para. 23:

http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/reports/html/166.htm#FN2

5 Megan Rowling quoting Thomas Hammarberg, Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights in: "Rights Chief urges Europe to make stateless Roma citizens", AlertNet 23 August 2011: www.trust.org/alertnet/news/interview-eu-governments-should-give-stateless-roma-citizenship-commissioner

6 Sherry R. Arnstein, "A Ladder of Citizen Participation", JAIP, Vol. 35, No. 4, July 1969, p 216.

7 Roger Hart, Children's Participation: from Tokenism to Citizenship, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Florence, 1992

8 "Youth on the Move", Analytical Report, European Commission, May 2011 http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_319a_en.pdf

9 Resolution of the Committee of Ministers (2008)23 on the youth policy of the Council of Europe

10 Have Your Say!, Manual on the revised European Charter on the Participation of Young People in Local and Regional Life, Council of Europe Publishing, 2008

11 The Charter is available here: www.salto-youth.net/downloads/4-17-1510/Revised%20European%20Charter%20on%20the%20Participation%20of%20YP.pdf

12 www.coe.int/t/dg4/youth/Source/Coe_youth/Participation/Have_your_say_en.pdf

13 Learn more on the European Youth Forum website: www.youthforum.org

compass-key-date

- 18 MarchFirst Parliamentary election with universal suffrage in Europe (1917)

- 5 MayEurope Day (Council of Europe)

- 12 AugustInternational Youth Day

- 19 SeptemberSuffrage day

- Week including 15 OctoberEuropean Local Democracy Week

- 5 DecemberInternational Volunteer Day for Economic and Social Development

- 10 DecemberHuman Rights Day

It is not always the same thing to be a good man and a good citizen.

Aristotle