Racial or ethnic profiling in policing has been defined as “the use by the police, with no objective and reasonable justification, of grounds such as race, colour, languages, religion, nationality or national or ethnic origin in control, surveillance or investigation activities”.[1] Though by no means new, this phenomenon is still widespread across the Council of Europe area, despite a growing awareness of the need to confront it supported by an evolving body of case-law.

Profiling the problem

There are several areas in which ethnic profiling may manifest itself more prominently. Government policies may provide excessive discretionary powers to law enforcement authorities, who then use that discretion to target groups or individuals based on their skin colour or the language they speak. Most often, ethnic profiling is driven by unspoken biases. One of its most prevalent forms is the use of stop and search procedures vis-à-vis minority groups and foreigners. A related pattern is the performing of additional identity checks or interviews of persons or groups at border crossing points and transportation hubs such as airports, metro and railway stations and bus depots. In certain contexts, persons belonging to minority groups have been prevented from leaving the country of which they are nationals.[2] Racial and ethnic profiling also occurs in the criminal justice system, with persons belonging to minority groups often receiving harsher criminal sentences,[3] sometimes also due to implicit bias which is increasingly being perpetuated by machine-learning algorithms.

According to the results of an EU-wide survey[4] carried out in 2015-2016 of over 25,000 respondents with different ethnic minority and immigrant backgrounds, 14% had been stopped by the police in the 12 months preceding the survey. In France, according to the results of a national survey of more than 5,000 respondents,[5] young men of Arab and African descent are twenty times more likely to be stopped and searched than any other male group. As for the UK - where police are required by law to collect and publish disaggregated data on police stop-and-search practices - Home Office statistics for 2017-2018 show that, in England and Wales, black people were nine and a half times more likely to be stopped as white people.[6]

Ethnic profiling of Roma exists throughout Europe. In addition, arbitrary identity checks of persons from the North Caucasus are reportedly common in the Russian Federation,[7] and police misconduct and harassment of suspected illegal migrants or black people has been reported in Ukraine[8] and the Republic of Moldova.[9]

A growing body of judicial decisions

National and international courts have shed a stark light on these worrying trends. In Timishev v. Russia,[10] the European Court of Human Rights held that no difference in treatment which is based exclusively or to a decisive extent on a person’s ethnic origin is capable of being objectively justified in a contemporary democratic society built on the principles of pluralism and respect for different cultures. As to the burden of proof, the Court held that once an applicant has shown that there has been a difference in treatment, it is up to the government to demonstrate that such difference was justified. More recently, in Lingurar v. Romania[11], the Court found violations of Article 14 (prohibition of discrimination) of the European Convention on Human Rights (the Convention) in conjunction with Article 3 (prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment) in a case of a racially motivated raid by police on a Roma household in Romania in 2011. In this ruling dealing with what it called “institutionalized racism” directed against Roma, the Court for the first time explicitly used the term “ethnic profiling” with regard to police action. A central finding of the judgment is that the authorities have “automatically connected ethnicity to criminal behaviour”, which made their action discriminatory.

In a case involving a family of African origin who were the only people to be subjected to an identity check on a German train, the Higher Administrative Court of Rhineland-Palatinate ruled in the family’s favour, arguing that police identity checks based on a person’s skin colour as a selection criterion for the control were repugnant to the principle of equality before the law.[12] In the Netherlands, the Supreme Court has questioned the discriminatory nature of a national police programme (known as the “Moelander” project) allowing the police officers to target cars with Eastern European plates when performing road checks.[13]

In Sweden, the Svea Court of Appeal examined a claim by several Roma persons concerning their inclusion in a Swedish police register solely based on their ethnic origin. The court requested the government to prove that there was another valid reason for including these individuals in the registry. As the government was unable to furnish the requested evidence, the court concluded that the persons’ ethnicity was the sole reason for their inclusion in the register, which amounted to a violation of the Police Data Act and of Article 14 (prohibition of discrimination) of the Convention in conjunction with Article 8 (right to respect for private and family life).[14] In France, in a case involving 13 individuals who complained about being subjected to identity control by the police because of their physical appearance, the Cassation Court held that the burden of proof lies with the authorities when credible evidence points to the existence of discriminatory practice.[15]

Algorithmic profiling

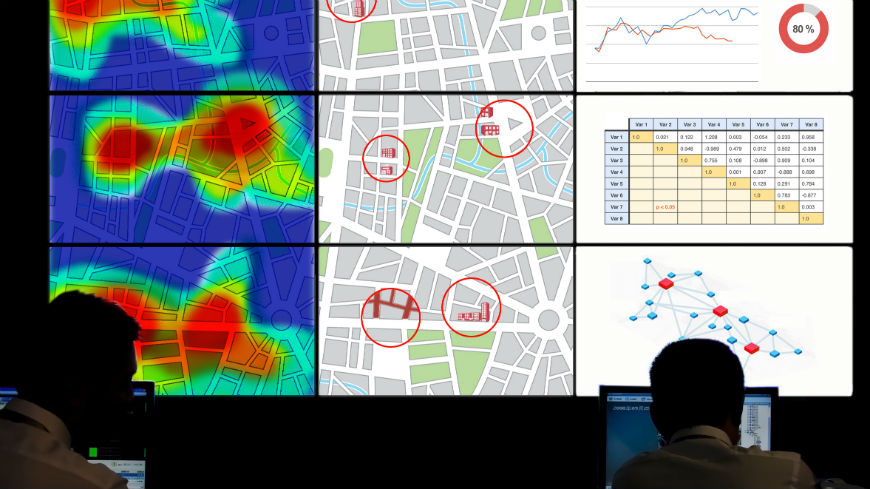

Though still in its experimental stages, the use of machine-learning algorithms in the criminal justice systems is becoming increasingly common. The UK, the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland are but a few European countries that have been testing the use of machine-learning algorithms, notably in the field of “predictive” policing.

Machine-learning algorithms used by the police and in the criminal justice system have sparked heated debates over their effectiveness and potentially discriminatory outcomes. The best-known examples are: PredPol, used to predict where crimes may occur and how best to allocate police resources; HART (Harm Assessment Risk Tool), which assesses the risk of reoffending for the purpose of deciding whether or not to prosecute; and COMPAS (Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions), used to forecast reoffending in the context of decisions on remand in custody, sentencing and parole. Apart from discrimination-related concerns, the right to privacy and data protection are major concerns associated with the use of algorithmic profiling. A 2018 report by the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies, a British defence and security think tank, acknowledged the fact that machine-learning systems like HART will “inevitably reproduce the inherent biases present in the data they are provided with” and assess disproportionately targeted ethnic and religious minorities as an increased risk.[16] A 2016 study by ProPublica questioned the neutrality of COMPAS when it found that whilst it made mistakes roughly at the same rate for both white and black individuals, it was far more likely to produce false positives (a mistaken `high risk´ prediction) for black people and more likely to produce false negatives (a mistaken `low risk´ prediction) for white people.[17]

Overcoming discriminatory profiling: prevention and remedies

Collection and publication of statistical data on policing - disaggregated by nationality, language, religion and national or ethnic background - is an essential step towards identifying any existing profiling practices and increasing the transparency and accountability of law enforcement authorities. Strategic litigation by the lawyers, NGOs and human rights structures, where relevant, would also contribute to increased awareness of the problem and compel to find appropriate solutions.

States should adopt legislation clearly defining and prohibiting discriminatory profiling and circumscribing the discretionary powers of law enforcement officials. Effective policing methods should relate to individual behaviour and concrete information. A reasonable suspicion standard should be applied in stop and search, and police should undergo continuous training in order to be able to apply it in their daily activities. Furthermore, law enforcement officials should be advised to explain the reasons for stopping a person, even without being asked, as this can help dispel perceptions of bias-based profiling and thereby boost public confidence in the police. Efforts to address discriminatory profiling should involve local communities at the grass-roots level; law enforcement agencies must engage with their communities to gain their trust and respect.

Moreover, in their communication with the media, the police should be careful not to spread and perpetuate prejudice by linking ethnicity, national origin or immigration status with criminal activity. The media, on its part, should avoid stereotyping persons belonging to minority groups, as well as migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers, as this can fuel racism and hatred and may contribute to the “normalisation” of discriminatory practices, including ethnic profiling. Instead, it should correctly reflect the positive contribution of minority groups to the communities in which they live and partner with schools, national human rights institutions and civil society to help build more inclusive and tolerant societies, including through human rights education programmes.

As long as the use of machine-learning algorithms to support police work is still at the experimental stage, governments should put in place a clear set of rules and regulations regarding the trial and subsequent application of any algorithmic tools designed to support police work. This should include a defined trial period, human rights impact assessments by an independent authority, and enhanced transparency and disclosure obligations, combined with robust data protection legislation that addresses artificial intelligence-related concerns. Machine-learning systems should benefit from a pre-certification of conformity, issued by independent competent authorities, able to demonstrate that measures were taken to prevent human rights violations at all stages of their lifecycle, from planning and design to verification and validation, deployment, operation and end of life.

Using solid and verified data in the process of developing algorithms for the law-enforcement authorities is vital. Feeding an algorithm with data that reproduces existing biases or originates from questionable sources will lead to biased and unreliable outcomes. For police services, the prediction of commission of crimes should not be only based on statistics established by a machine against an individual, but be corroborated by other elements revealing serious or concordant facts. Legislation should include clear safeguards to ensure the protection of a person’s right to be informed, notably to receive information about personal data and how it can be collected, stored or used for processing.[18]

Access to judicial and non-judicial remedies in cases of alleged ethnic profiling, including those stemming from the use of machine-learning algorithms, is also crucial. National human rights structures, including equality bodies, as well as independent police oversight authorities should play an increasingly active role in detecting and mitigating the risks associated with the use of algorithms in the criminal justice systems. They should closely co-operate with data protection authorities, making use of their technical expertise and experience in this matter. Courts and human rights structures should be equipped and empowered to deal with such cases, keeping up to date with rapidly developing technologies. Finally, governments should invest in public awareness and education programmes to enable everyone to develop the necessary skills to engage positively with machine-learning technologies and better understand their implications for their lives.

Dunja Mijatović

[1] European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI), General Policy Recommendation No 11 on Combating Racism and Racial Discrimination in Policing, CRI(2007)39, 29 June 2007, page 4.

[2] “The right to leave a country”, Issue Paper published by the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, 2013.

[3] In the United Kingdom, the Lammy Report (2017) found that minority ethnic individuals were more likely to receive prison sentences than defendants from the majority population.

[4] Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey (EU-MIDIS II) carried out by the European Union’s Fundamental Rights Agency.

[5] Enquête sur l’accès aux droits, Volume 1 – Relations police/population : le cas des contrôles d’identité, Défenseur des droits, République Française.

[6] https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/crime-justice-and-the-law/policing/stop-and-search/latest

[7] Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, Fourth Opinion on the Russian Federation, adopted on 20 February 2018, ACFC/OP/IV(2018)001.

[8] Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, Fourth Opinion on Ukraine, adopted on 10 March 2017, ACFC/OP/IV(2017)002.

[9] European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, Report on the Republic of Moldova (fifth monitoring cycle), adopted on 20 June 2018, CRI(2018)34.

[10] Judgment of 13 December 2005, applications nos.nos. 55762/00 and 55974/00.

[11] Lingurar v Romania, judgment of 16 April 2019, application no. 48474/14.

[12] http://www.bug-ev.org/en/activities/lawsuits/public-actors/discriminatory-stop-and-search-cases/racial-profiling-on-the-regional-train-to-bonn.html

[13] https://www.fairtrials.org/news/plate-profiling-dutch-supreme-court-questions-discriminatory-police-road-checks

[14] https://crd.org/2018/03/25/historic-victory-in-the-court-of-appeal/

[15] https://www.courdecassation.fr/communiques_4309/contr_identite_discriminatoires_09.11.16_35479.html

[16] https://rusi.org/sites/default/files/20180329_rusi_newsbrief_vol.38_no.2_babuta_web.pdf

[17] https://www.propublica.org/article/machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminal-sentencing

[18] See the Council of Europe Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data, 1981.