Keynote address 'The Artist as Defender of Human Rights', by Michael O’Flaherty, delivered at the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin, Ireland, at the Special Evening Lecture organised as part of the exhibition La Grande Illusion by artist Brian Maguire on 9 October 2024.

When I was a child of eight or nine years old, I was taken by my aunt, my Auntie Kathleen, for my first visit to the National Gallery here in Dublin. As we walked around the rooms, I asked one of the guardians: “What is the most important picture in the gallery?” Without a moment of hesitation, he took me to the doorway and pointed into the next room and said: “That is it.” I went over.

It was that marvellous little piece by Fra Angelico that depicts the attempted martyrdom of Saints Cosmas and Damien. It is small, 37 by 46 centimetres, but it is a remarkable painting. In the first place, it is exquisitely beautiful, but on examination, it's also complex, dealing with layer upon layer of storytelling.

It is highly dramatic, as you can see in the image there, and it is unforgettable. In fact, for me as a little boy, this is a strange thing to say now in reminiscence, but it was thrilling and unforgettable. That was my first experience of great art.

My most recent experience of spending a concentrated amount of time in front of a piece of art was just a few weeks ago, confronted by Brian Maguire's Maragua Land, painted in 2023. A considerably larger painting than the Fra Angelico, but equally beautiful, and as you can see again from the image, highly dramatic, deeply ambiguous, telling multiple stories all at once, depicting natural beauty and its destruction, its destruction by humankind. And I would suggest that ultimately, this art is hopeful. It indicates regeneration. That's what I think I see in the foliage. And I even see the symbol of hope, the soaring bird, at least I choose to see the soaring bird in the top right-hand corner.

These two works, separated in my life by over 50 years, and in history, one from the other by 600 years, have in common a search for truth, a recognition that truth is complex, but that it must be sought. The story must then be told, and it must be told well, told in a way that renders it capable of reaching our hearts as well as our minds. And both paintings, I think, have that quality of ultimate vindication of hope.

Now, whether or not hope is ubiquitous in great art is a matter of some debate, but I find it commonly present in the very finest pieces. And there is one further quality invariably to be found in great artists, and that is courage. It takes guts to tell the truth.

Look at this work by Liliane Tomasco. Here we see astonishing weaves of colour. They stand, according to the artist herself, as proxies for emotion, and that as these proxies, they burrow deep, they bring us deep into the heart of the inner being, the truth of what it is to be human. This work and others like it are extraordinarily intimate, deeply self-revelatory for good and for ill, and I think its depiction requires great strength, great courage.

It is taking account of these qualities inherent to so much great art and to great artists, that of truth seeker, truth teller, guardian of hope, person of courage, it is taking account of these that it comes as no surprise that artists through history have been preoccupied with upholding, respecting, demanding respect for human dignity. And this profound humanism is rampant across art of all disciplines, schools and centuries.

Think about how Christ is depicted in Western art. Look at almost everything that Caravaggio painted. In other disciplines, think about the music of Benjamin Britten or the writings of Dostoyevsky.

Coming back to the visual arts and right up to the past century, look most obviously at Picasso's Guernica. These days, it is almost banal to use this work as an illustration of anti-war art, but it is no less a fact for that. What is more, this painting continues to challenge us on a daily basis.

A version of it in tapestry hangs outside the UN Security Council in New York, where I once worked, and I saw with my own eyes how day in, day out, as each diplomat had to pass the tapestry, they were recalled into a reminder of why they were there working for peace.

The championing of human dignity on the part of artists intensified in the 20th century. This intensification was in parallel with efforts to map out the requirements for the honouring of human dignity in the form of codes of human rights.

The development of the modern human rights vocabulary picked up speed during the Second World War, a noteworthy moment of which was a speech by President Roosevelt identifying what he called the four freedoms. Freedom from want, freedom of speech, freedom of worship, and freedom from fear.

And out of this grew an ever-intensifying debate which led to the adoption eventually in 1948 by the United Nations General Assembly of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, following a drafting exercise led by Eleanor Roosevelt.

To this day, the Universal Declaration carries within it the great core ideas of the modern human rights system. In the first place, it addresses all aspects of human well-being. It is for sure about what are called civil and political rights, things like the right to vote, right to a fair trial, freedom of assembly, association, expression, but also the no less important entitlements to the basics for dignified living like access to food, to shelter, to health care, to the opportunity of having a job. The universal declaration also identifies the responsibility of all of us to respect each other’s rights.

The rights contained in the Universal Declaration came to be developed further and in greater detail as binding international treaties at the United Nations level, here in Europe at the level of the Council of Europe, and indeed across regions of the world.

One central aspect of the human rights system as contained in the Universal Declaration and the treaties that followed is that it is unique.

It is universally agreed time and time again. All states, no matter how abusive of human rights, have acknowledged that the Universal Declaration applies everywhere at all times. This global or universal quality of buy-in to the Declaration is a key element that gives it its force and its power and it's also why we have to constantly remind that there is no alternative to human rights as a shared vocabulary to honour human dignity. There is no other universally agreed road map. Let's put it like this: there is no plan B. One final aspect of human rights to consider is that it binds states – at everything from the central government to the level of the village.

Here is a moving depiction of that reality in the form of a cast of the shoes of Roosevelt and one of her most famous quotes “Where do human rights begin? In small places. Close to home”. (the cast is held at the UN headquarters in New York). This cast is an example of the remarkable extent to which art practitioners have directly, specifically engaged the modern human rights system in their own production.

Probably the first instance of this explicit recognition of the modern day human rights system is in the famous four paintings of Norman Rockwell, The Four Freedoms (below freedom of speech).

Of course, you see it extensively represented in the art collections of great global and regional organisations. My own organisation, the Council of Europe, houses a good collection built up over decades, including, for instance, Spanish artworks each of which actually carries the title Human Rights. There is the group sculpture located on the lawns outside the Palais de l'Europe by Mariano Gonzales Beltran and the piece by Antoni Tapies that hangs within the building.

Ireland also has given an artwork to the Council of Europe, Patrick Scott's Ray of Sunshine on a Wave, a beautiful tapestry which I believe has a strong human rights resonance. Despite its title those lines suggest to me the human fingerprint overlaying a dazzling galaxy of rainbow-like colours. This in turn speaks to me of the person in the world, acknowledged in all their individuality.

The engagement of the arts with human rights extends well beyond the visual arts. Think for instance of the work of Seamus Heaney and his great poem Republic of Conscience, which was commissioned by and specifically written in the context of the work of Amnesty International.

Think also of groups of artistic practitioners who have deliberately come together around the context and the frame of human rights in order to do their job in a different way, in a better way, in service of humanity. One group that I know well is Musicians for Human Rights which plays a valuable role in promoting human rights, not only through music but through the direct engagement of the musicians with marginalised communities.

Friends,

Interesting work has been carried out in recent years in assessing and better understanding the engagement of the world of the arts with human rights, to categorise it, to identify its diverse forms and shapes. This, for instance, was the subject of a conference that I organised when I led the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights. It has also been the subject of a summer school that I organised in 2015 at NUI Galway. And in many other institutions globally.

Drawing from this work, and fully aware of the risk of reductionism, let me suggest six contexts in which the artist and human rights engage. Of course, this cannot be an exhaustive list and I also acknowledge that a piece of artistic expression will often address more than one of the contexts. As I illustrate them I can, in almost every instance, reference the work of Brian Maguire.

First, there is the role of the artist in honouring the human, in describing the human imbued with dignity, inviolable, because that is the human at the heart of the human rights system. This is very well exemplified by this piece by Brian Maguire, Rosie Kenmille. He painted one of the missing and murdered indigenous people in America, based on a photograph chosen by her family. I think you will agree with me that it is a deeply respectful portrait of the young woman, honouring her and her identity despite the tragedy behind her story.

Another example of this genre is Augusta Savage “Gamin” already executed in 1929. This piece was considered very unusual when produced because it uses the artform of the monumental bust to capture the likeness of a poor African-American child living in poverty in Harlem, New York.

Moving on to the second function, and by far the best known and the most illustrated, and that is the role of the artist in recording reality. Again, it is a dimension so magnificently addressed by Brian Maguire in Aleppo 4. The painting vividly captures the horror of war, without a trace of sentimentality or propaganda. In its painterliness, it tells a story that a thousand photographs could not convey. It is unforgettable.

Another artist who has played a very important role in conveying reality in reporting in a way that is so much more powerful than the non-artistic form of expression, is Botero. His paintings of the atrocities perpetrated in Abu Ghraib prison are astonishing. I saw them in an exhibition in Rome, and I immediately sensed how much more effective they were in depicting the horror than had been those pictures taken on a phone which had triggered the exposure of the shameful behaviour.

And let us not forget, as I said earlier, the artist has long recorded the horrors of war. Goya was heavily invested in this task over two hundred year ago (Francisco Goya, Que Valor !).

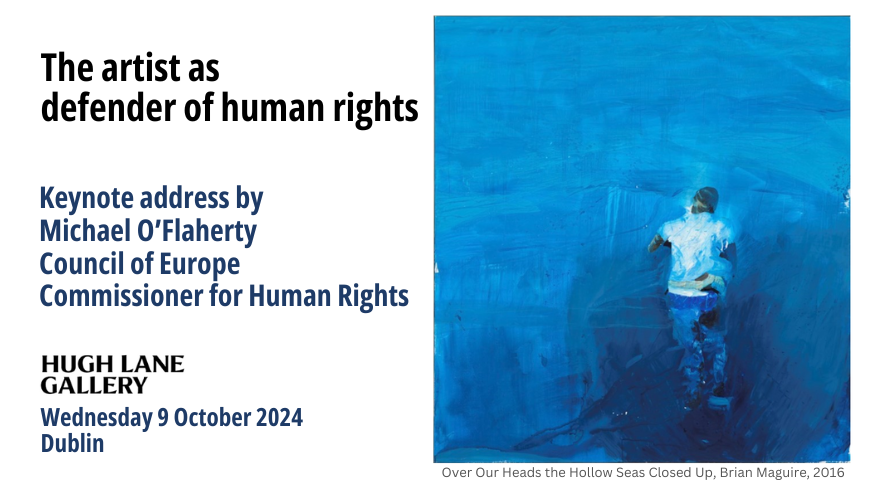

Third, there is the role of the artist in the memorialisation of human rights stories, human rights tragedies, the tragedies of human beings. Again, here in one of the most powerful, I would argue, one of the most powerful and unforgettable paintings in the current exhibition, there's Over Our Heads The Hollow Seas Closed Up by Maguire. I can barely find the words to acknowledge the power of this work as a show of deep respect and of honour not just to one anonymous victim but to all those who drown senselessly in our seas.

For a very different form of memorialisation, have a look at the memorial by Louise Bourgeois for the victims of the witch trials in Norway that had resulted in the execution of 91 people, mostly women.

A fourth dimension of the work that artists often choose to engage is the expression of outrage, expression of anger, at the degree, at what we will tolerate in our world, what people will allow to happen. This is already evident in some of the work we’ve look at this evening. Have a look also at another work by Brian Maguire Arizona 1. This is so clearly a work of fury and outrage. It is certainly not meant to be easy to look at.

To move to another area of the arts, look at the, or pay attention to that great book of Stéphane Hessel, Indignez-vous, his cry of outrage at the extent to which we are squandering our human rights inheritance so carelessly in the present time.

A fifth dimension of the role of the arts in supporting human rights and engaging with human rights is in the form of a celebration of identity, celebration of diversity, celebration of culture.

Right now, I am spending a lot of time visiting Roma and Traveller communities across Europe, including this week here in Ireland. And I am frequently struck by the power of Roma artistic expression, and indeed its ability, if it is better known, understood and appreciated, to build bridges across communities.

Have a look at Family/Garden of Dreams, executed in 2018 by the Roma artist Ornella Rudeviča. She described the work as a celebration of family and living traditions that are centuries old.

Sixth, and the final of the contexts of engagement of the arts and human rights in my non-exhaustive list, is in the role of the artist in pointing to possible futures, different futures, futures in which human rights will have grown and developed to embrace new human realities.

One such reality, of course, is the climate crisis. Again, Brian Maguire confronts us with this in some of his more recent work: The Clearcut Amazon. In this great painting, I see again those warnings and calls to action that are also present in Maragua Land. It is difficult to contemplate such paintings without realising that we have to drastically change the way we engage with our world.

Moving to another artistic discipline, Kazuo Ishiguro, in his recent work, Klara and the Sun, challenges us to think through the implications for human well-being of robotics, echoing issues that currently preoccupy human rights activists and regulators.

Before proceeding any further, let me express some caveats, some calls for restraint in terms of the relationship of the arts and human rights, or at least reflexions on possible limits to that relationship. Again, this is not an exhaustive list.

The first is the danger that we instrumentalise the arts. There is a danger, certainly speaking from the human rights community side, that we take art and use it for our purposes, to objectify it in our own interests. This has to be avoided with great care. Any instrumentalisation of art would be, I suggest, a destruction of that art. Its power is in its autonomy, and we must treat that autonomy with the greatest of respect.

Secondly, and again, directed to the human rights community, we have to avoid any form of colonisation of the engagement of the arts with society, with humanity, with human well-being and thriving. Not everything is about human rights. Not everything is intended by the artist to be about human rights. There may often be an accidental correlation, and that is fine, but the artist must remain entirely entitled to articulate his or her visions for our world, for individuals, for society, within their own terms of reference, which may not be those of human rights actors.

My third caveat has to do with the avoidance of excessive expectations from our collaboration. We should not expect that artistic expression is going to solve some great issues of the world.

Art can and does and repeatedly has played a very important role, but no more than that. I think, for instance, of that very important moment of artistic expression, of the playing of the cello by Vedran Smailović in the destroyed library in Sarajevo back in 1992. That was a vivid moment which brought home the horrors of the war to people all over the world.

It plays its essential role in the narrative in terms of how we would respond to the horrors. But it, of course, in and of itself, did not and never could have stopped that war.

Still another caveat is the recognition that art can actually do harm. I do not have the time today to explore this in any great depth but let me simply refer to inadvertent harm. Because there have been cases where artistic expression, intended to be a legitimate expression, rather respectful of human beings and human rights, has turned out to be something rather different.

I will use an Irish example.

A few pals and I, we were students at the time, came into Dublin to what is now the National Concert Hall to look at the so-called Martello Tower of Bread that was erected in the context of the ROSC ‘80 exhibition. The reason for being there that evening was that it had been announced that this monumental piece of art was going to be demolished and that people could take the bread away.

We went for the lark just to get a bit of bread for breakfast, but what we did not expect was the extent to which a crowd of really hungry people turned up and desperately grabbed at that bread to bring it home. I felt a sense of deep embarrassment that they were put in this humiliating situation and I suggest to you that this is an example of where a well-intentioned expression can actually have very sad consequences.

The last of my caveats in terms of the engagement of the arts and human rights has to do with issues of access to the arts. To the extent that the arts are inaccessible, their engagement is so diminished in terms of its impact on any or all of us. There are so many dimensions of access that we could explore but let me start by saying how proud we should be here in Ireland that we have kept access to our great galleries and museums free of charge. This is something we are in danger of taking for granted but it is so important.

Just look at the damage that I think was done when the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York went from a donation-based entry system to a very expensive dollar price to gain admission. One can only imagine the number of people that as a result were excluded from engaging with the great art present in that institution.

Enough of the caveats. I do not want to give any impression that somehow the partnership of the artistic community and human rights should not be intensified. It has never been more needed than now.

Look, just look around us. Look at our world and the extent to which human rights are being violated and are under extreme pressure. Because of the nature of my work, I see that for instance in the conflict in Ukraine or rather the aggression against Ukraine and every dimension of it. I met just a few days ago a group of mothers and wives of people abducted into Russian-controlled territory, and I cannot begin to convey to you their pain or the suffering that I encountered in that meeting.

I also think of the horrors in the Middle East, not just the dreadful conflict on the territories of the region but also the impact of that conflict in terms of rising patterns of antisemitism and anti-Muslim hatred across Europe. I think of the situation of the communities I mentioned earlier, Roma and Travellers: 12 million people across Europe pushed to the very edges of our societies. I think of the treatment of asylum seekers on so many borders put in very real danger, never mind all those who drown in the Mediterranean and elsewhere.

I think not only of the violations of human rights but also of the repudiation of the human rights system, of how it is increasingly acceptable to say that if you do not like the human right, well you will disregard it, you will disregard the treaty, you will disregard the commitment. I think of the rhetoric associated with populism and the rise of the radical right. I even think of the extent to which it has become fashionable in our elite intellectual discourses to treat human rights as something that is past its sell-by date, that could be replaced by something else.

And remember what I said much earlier: there is no plan B. There is no other universally agreed roadmap to honour human dignity. As I said, we have to intensify our engagement with each other in standing up for this remarkable achievement of modernity.

Let me conclude with three specific suggestions, three specific areas for that collaboration.

The first is that in we need to strengthen our cooperation and partnership. We have to do a better job of standing up for artistic practitioners and art practitioners themselves. I am aware of the extent to which arts practitioners in different places come under different forms of pressure, severe violations of their own human rights.

Ai Weiwei’s Remembering is an installation of 9,000 school backpacks that covered the Munich Haus der Kunst museum’s façade in 2009 to commemorate the pupils who died in 2008 after an earthquake devastated Sichuan province in China.

The sentence on the façade is from a victim’s mother and it reads: “All I want is to let the world remember she had been living happily for seven years”.

Following accusations from parents that substandard construction caused the collapse of schools across in the region, Ai Weiwei set upon a political investigation that would name every missing student and call the government to account for their deaths. This investigation brought about Remembering which, according to the Guardian newspaper “changed his career forever”. According to the paper, it is the artwork that made him the most dangerous person in China and sent him to jail.

It is essential that they we identify artists like Ai Weiwei (and Brian Maguire) as human rights defenders and find ways to support them as such.

This involves not only acts of solidarity but also, on the part of states, offering humanitarian and respite visas to artistic practitioners under pressure where they come from. It means defending artists in the courtroom, giving them a voice in international human rights fora. It means accompanying them and developing tools as well as spaces to enhance their safety.

Second, we have to create locations of encounter, more opportunities, more spaces within which the artistic and the human rights communities can engage, get to know each other better, intermingle. In this context, I so very much welcome a number of initiatives in recent years.

I have mentioned Musicians for Human Rights but let me focus on Art for Human Rights, this wonderful organisation founded by Bill Shipsey from Dublin, originally for Amnesty International, that plays an important role in bridging the divide to the betterment of our societies.

Look at the attention that this organisation has received for donating a bust of Liu Xiaobo to the University of Galway just a few weeks ago. This artwork located in a public space in the University, will undoubtedly trigger necessary debate and reflexion around issues of human rights.

Third, and final of my three suggestions today has to do with investing in mutual literacy. I am not competent to speak to the extent to which an artistic practitioner could become more formally literate in the area of human rights, other than to suggest that it be included in the curricula of all art schools if it is not already there. But certainly, we in the human rights world need to become more literate regarding the breadth of artistic communities and the potential for engagement and cooperation in our shared goals. This of course in turn would trigger the value of including in the curricula of human rights programmes, of which there are so many around the world today, a deep appreciation of the diversity and the breadth of the arts and the potential for co-operation.

Dear Friends,

You have heard enough from me. Before I conclude, let me tell you that I am well aware that I have not referred to a vast amount of relevant topics. If time had permitted, we should also have explored such issues as appropriation, colonialism and restitution. I would also have liked to plunge deeper into the relationship of art with individual and group identity. I am also aware that my artistic references are predominantly western – that is a reflection of my own limited exposure to the art world.

To conclude, I would like to come back to this exhibition and its title, La Grande Illusion, a deliberate reference to the 1937 film by Jean Renoir, a work that has been neglected for many years despite its importance as a beacon of hope and encouragement. The film is highly complex, multi-layered, difficult to penetrate. Nevertheless, there is widely agreed that it is ultimately a powerful statement about how we can make a better world.

The British Film Institute, in a recent review of a newly restored copy of the film, described La Grande Illusion as offering us a glimpse, not of our destiny, but of a dream worth striving for. It also said that while La Grande Illusion emphasises a common humanity that transcends class, geography and faith, it also argues that if we want a better world, it is not sentiment but effort that is required.

These words sum up everything I wished to say this evening and they describe, without doubt, the great work of Brian Maguire.

Thank you.