Part II . Processes and actors

There are at least three generic “models” of democracy circulating among theorists and practitioners in contemporary Europe. Each of them places primary responsibility on different types of actors and processes of decision making. In order to guide our collective thinking on the challenges and opportunities facing these actors and processes, we propose to use a generic working definition of democracy that does not “commit” to any specific institutional format or decision rules. By leaving open the key issues of how citizens choose their representatives, what the most effective mechanisms of accountability are and how collective binding decisions are taken, this definition does not preclude the validity of what we shall later call “numerical”, “negotiative” or “deliberative” democracy.

Modern political democracy is a regime or system of governance in which rulers are held accountable for their actions in the public realm by citizens, acting indirectly through the competition and co-operation of their representatives.

This definition provides us with a tripartite division of labour. Three types of actors combine through a variety of processes to produce the sumum bonum of political democracy, namely, accountability. We have, therefore, divided our analyses of contemporary transformations and responses into those primarily affecting citizenship, representation or decision making.

Citizenship

Political discontent

Today, one of the most striking features of European democracies is an apparently widespread feeling of political discontent, disaffection, scepticism, dissatisfaction and cynicism among citizens. These reactions are not, or not only, focused on a given political party, government or public policy. They are the result of critical and even hostile perceptions of politicians, political parties, elections, parliaments and governments in general – that is across the political spectrum.

Political discontent expresses itself in opinions, attitudes and deeds. Some citizens give utterance to their political disappointments or angers through day-to-day talks with friends or relatives. Social scientists try to analyse such opinions through polls, or in-depth interviews. The more intense these opinions or attitudes, the more likely they are to lead to actual deeds. In the political sphere these deeds are often “non-deeds”. Many disappointed or angry citizens refrain from voting or from joining a political party. Others explain that they are so angry with (established) politicians and political parties that they intend to cast a vote for some outsider, protest, or radical political party. Discontented voters are thus more likely to make unstable electoral choices, which partly accounts for the unprecedented high rate of turnover in the composition of governments.

Whether expressed through talks, polls or interviews, opinions may be (more or less) fragile, volatile, dependent on context, and even artificial. That is the reason why acts are more significant than words. Even if electoral participation is affected by many factors and cannot be reduced to satisfaction or dissatisfaction with politics, its evolution may provide a rough, but nonetheless informative view of the spread and growth of political discontent.

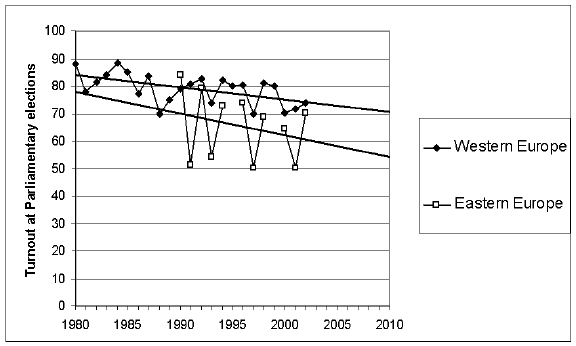

Figure 1: Turnout at parliamentary elections in Western and Eastern Europe

Sources: Figure 1 measures the evolution of the mean yearly turnout at parliamentary elections in all Council of Europe member states since 1980. It is based on electoral data of the member states with a population of more than 1 million which were members of the Council of Europe before 1980 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom). Such a grouping is obviously artificial, but it illustrates the overall declining trend of electoral participation in Europe and, consequently, the seemingly growing political discontent which partly determines voter turnout. Data for Eastern and Central Europe have been processed analogously and take into account voter turnout at parliamentary elections in seven states (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovak Republic). These states have been chosen because they have a population of more than 1 million inhabitants and because they have been a member of the Council of Europe for more than ten years after 1990.

“European” voter turnout has decreased from 88% in 1980 to 74% in 2002, and even 70% in 2000. Electoral participation is declining – with a more or less gentle slope – in all countries except Denmark. If we extrapolate the past overall tendency, turnout will be close to 65% in 2020, and even lower if we take into account the voting-age population instead of the registered voters. The decline in electoral participation is even more marked in Central and Eastern Europe. In this region, the weighted mean voter turnout has moved from around 70% at the beginning of the 1990s to 60% just ten years later. It would decrease to around 45% at the beginning of the 2020s if we extrapolate its evolution over this brief period. These conclusions are backed up by opinion polls, showing a clear downward trend of trust in parliaments in Europe.

Attitudes towards the political realm are however more ambivalent than opinions of discontent may suggest. National parties and politicians, that is to say specialised and professionalised political actors, are much more criticised than those on the local level. In other respects, people make distinctions among various political levels or dimensions. Some of them, belonging mostly to upper middle and upper socio-cultural strata, see differences between a “politicking” component, which refers to parties, politicians, elections, rivalries and struggles for power, and a non- or less-“politicking” aspect, associated with projects, programmes, issues, ideas, principles, convictions and efforts to solve problems. When people in this category criticise politics, they usually (tacitly) think of the former dimension while refraining from criticising the latter. Some of these most censorious citizens are willing to believe in politics when a leader or a party appears “different” to them or when crucial issues (terrorism, fascism, welfare state) are at stake.

The way people perceive and criticise the political realm depends on their political investment and skills. Two different types of discontent may must be distinguished: a rather simplistic and timeless one and another more sophisticated type. The former has been around for a long time, well before politicians and political scientists began to worry about distrust in political institutions and actors. It is older than the political changes (for example globalisation, “de-localisation”, the “crisis” in nation-state capacity, rising unemployment, European integration) often singled out as explanations for political disaffection. Discontent of this type is easily – perhaps too easily – picked up by opinion polls. Respondents who share these views belong, at least statistically, to definite segments of the public which are characterised by:

- a rather low (but somewhat unequal) level of education, social status, political information and sophistication, and a feeling of personal political incompetence;

- no marked political preferences and even an inability to perceive differences between politicians and parties;

- a fear of “being had” by politicians because of this incompetence;

- a lack of interest in politics which leads to thinking and arguing that politics does not deserve their attention;

- a narrow vision of politics, mainly reduced to the above-mentioned “politicking” dimension, as a consequence and a determinant of this lack of interest;

- bad living conditions that prompt people to think that politicians do not really care about them and, therefore, that politics do not matter.

At the same time, other people express more sophisticated feelings of discontent. Contrary to those who may be subsumed within the previous category, they refer to various shifts in the political realm. They say, for instance, that “there are not many differences among political parties nowadays”, “left- and right-wing parties are presently very similar; they pursue and drive the same policies”, “politics is increasingly lukewarm”, “it's no longer important, it's economics that matter now”, “nation-states can't do much against firms' decisions to relocate”, or that “the EU decides on everything”. These opinions are held by people who add that they used to be, but are presently much less, interested in politics and that their political preferences have waned. Nevertheless, many of them still have strong negative preferences, in the sense that they are strongly opposed to some political parties. They also pay enough attention to politics to be able to criticise political actors, using informed arguments. People who may be classified in this second category have a higher (but not necessarily a very high) level of education. They are more interested in, informed about and confident in their ability to cope with politics than those in the first category, and have a more complex, diachronic, and even lofty view of it.

Causes and explanations of political discontent

Political discontent proceeds from a set of convergent factors.

Education. The higher the level of education, the higher the feeling of political competence. The higher the subjective and objective political abilities, the higher the criticising capacities and tendencies. Increasing cognitive competence among citizens increases capacity for criticism, and a greater willingness to criticise if something appears to be wrong. A more educated citizenry has a more critical mind and is potentially more demanding with its political leaders and representatives. More educated citizens also tacitly wish to be more active, even if they are not ready to invest time and energy when they are really asked to participate in something. Demands for more significant and direct forms of political participation are therefore real, although somewhat ambiguous. One of their real effects is perhaps that the significance of voting for representatives, as the most important form of democratic participation, is bound to diminish. A small but seemingly growing number of (relatively) educated citizens are more or less plainly asking for greater opportunities to express their own opinion and to decide by themselves on important subjects.

Changing values. European citizenries or, at least, large segments of them, seem to have shifted from deference to authority and authorities to scepticism of elites and institutions. But, for numerous and complex reasons, a growing pervasive permissiveness and intolerance of social norms and authority has been spreading for a long time. A growing culture of rights, equality and personal autonomy is somewhat contradictory to the deference, compliance, discipline, hierarchy and leadership that organise citizens-representatives relations in a representative democracy.

Economic shifts. Economic growth has been weak during the last three decades. Unemployment has increased. Real wages have remained stable or have grown only slowly for years. Declining trade barriers and transportation costs and improvement in communication have enhanced the role of international trade and investment in all economies. Global competition brings various advantages to some categories, but also entails relocation of firms to low-wage countries, depression of wages in advanced countries and downward competitive pressures placed on labour standards. New technologies are also eroding skilled labour and wages, even if they help to create new skilled jobs at the same time. Globalisation has challenged the capacity of the states to provide effective regulation in the economic and social domain. New institutions like the European Union or the World Trade Organisation have weakened nation-states' policy latitudes. They have also suggested that nation-states may become a less significant collective actor. Nation-states are also hollowed out by deregulations and privatisations. Governments have at the same time faced a “fiscal crisis”, and tried to balance budgets by containing public sector outlays. Social services have been reduced or their expansion has at least come to an end.

A growing number of citizens have been increasingly confronted with problems resulting from global economic competition, economic crisis and diminishing welfare protection. Those who personally, or whose relatives, endure or fear unemployment, and those who think their economic situation will worsen, are more prone to a negative perception of politics. People who already thought that politics could not improve their life and that there was nothing to expect from politicians have seen their opinion confirmed.

Dramatic and highly salient woes, whether “objective” or “imagined”, like recessions, rising immigration, loss of local control, unemployment, and insecurity, have led some segments of the public to share the conclusion that government was handling problems poorly and was failing to keep its promises, whether they were personally affected or not, and regardless of achievements in other areas.

For more sophisticated segments of the public, the level of political discontent is also linked to more complex evaluations of governments' performances. The successful economic policies of governments during the first thirty years after the Second World War and the subsequent downturn of the mid-1970s have raised and then disappointed expectations of state capacity to deal with growth, inflation and employment. Poor or poorer states' economic performances of the last decades have seemingly been assessed with reference to the economic boom of the thirty “glorious” post-war years, and also through expectations arisen from a century of expanding public interventions.

The most sophisticated segments of the public are more aware of the economic and social changes of the last decades. They do not reason as if no change has occurred. They think that the nation-state is no longer able to deal with major economic difficulties, that it cannot oppose the decisions of international companies and prevent de-localisations of plants. Their expectations of what governments are able to accomplish are diminishing. However, they still remain unsatisfied with politics because they tacitly compare present governments' performances with prior ones, or with their developed normative views of what governments should do. Both normative and ideological expectations thus provide critical resources which are activated by what appears as government failures. The conjunction of growing critical resources due to higher education and numerous political disappointments give rise to permanent critical dispositions in the politicised strata of the public. These critical leanings are activated when people face personal difficulties, whatever they may be, in their own life.

Political context. When people explain their political disappointment, they refer or allude to various elements of social and political contexts to vindicate their disillusions. One observes that dramatic revelations of political corruption and scandals in numerous countries have fostered a climate of ethical distrust.

Ideological and political distances among political parties have been reduced. In various European countries, politics was, but is no longer, regarded as a struggle between contrasting, even utopian, views of society and its future. Since the collapse of the “real existing” socialist system, almost no established party intends to overthrow the market economy, capitalism and liberal democracy. For various reasons mentioned before, governments' leeway has also been reduced. This has led some segments of the public to the conclusion that politics does not matter anymore, that it is not worth losing time to decide between similar parties, defending similar policies, and that parties and politicians are competing only to enhance their own power and privileges. Those who have kept some partisan attachments deeply regret that left-wing parties support what they regard as “neo-liberal right-wing” policies, or that right-wing parties leave unchanged “socialist left-wing” policies when in government. Some citizens feel that politics has lost authenticity, and is increasingly run by self interest and ulterior motives. They even sometimes allude to opinion polls and communication specialists as having caused these changes.

Recurrent episodes of political life that were perceived as neutral or normal in the past now fuel political distrust when this distrust has become high enough to produce a bias against politics itself. The current and frequent bashing, bad mouthing and blaming of “the government” by elected and selected representatives thus help to develop increasingly negative perceptions among segments of the public already prone to reducing politics to “politicking”.

In order to maximise their audience, the media tend to simplify, personalise, dramatise and stress the “spectacular” aspects of political events. They cover politics rather than policies, focus on scandals, tactics and personal rivalries, and describe electoral campaigns as if they were “horse-races”. Candidates and public officials are often depicted as duplicitous and self-serving. The media tends to reinforce the fears and prejudices of those among their consumers who see all politics as merely “politicking” – if only because this makes the information more entertaining and easy to understand. This is especially the case for those “citizen-consumers” who are only slightly interested in the subject and already prone to mistrust politics due to their attitudinal predispositions, social marginality and lack of trust in institutions.

Does political discontent matter?

Is the apparent increasing level of political discontent threatening the legitimacy of European polities? First and foremost, political discontent is ambivalent and the present disenchantment is potentially reversible. A second point is that there is an ambivalent decreasing confidence in politicians, parties, elections, legislatures and governments, but apparently no pervasive distrust of other dimensions of European polities. The legitimacy of a political system depends on the existence of an alternative and competitive polity or utopia, and the struggle over different forms of governmental and societal organisation has disappeared at least since 1989. Some scholars argue that since the collapse of the socialist system, citizens' support for democracy is becoming increasingly dependent on governmental performance, especially in former socialist countries. Democratic systems seem thus more vulnerable, but also unquestionable and stronger at the same time.

For the same reasons, a high and growing level of electoral abstention is not a threat to the political system per se. But as abstention increases with lower social rank and as politicians are more eager to take voters' than non-voters' expectations into account, declining electoral participation should tend to introduce or strengthen the class bias in public policies.

The lack of confidence in political institutions raises the question of the willingness of the public to comply with laws, to pay taxes or to enter administrative careers. Several isolated acts of violence against politicians and officials perpetrated in some countries could be linked to a growing political discontent. Ethical distrust of politicians is already a serious problem since it weakens dispositions to comply with rules and laws. Young criminals say, for instance, that they do not feel ashamed of their thefts, robberies, or drug dealings, because “political leaders have stolen much more than we have”.

Cultural identity and protest

Migration, defined as the movement of persons from one region or country to another, irrespective of motivation, gives rise to important population changes which affect democratic life in Europe. Migration diversifies the composition of the European demos as it causes people with different legal status to co-habit under the same democratic roof; along with national citizens there are guest workers, long-term residents (or denizens), asylum seekers and undocumented migrants. All these groups of people, because of their legal status, are subject to different sets of rights and obligations.

Democracy, citizenship and rights

a) Levels and characteristics of migration

Since 1989 net migration has been the main factor impacting annual population change in Council of Europe member states. Figure 2 below presents the trends in the change of stock of foreign population as a percentage of the total population for fifteen countries in Europe. The total recorded stock of foreign population is approximately 21 million people in 1999 amounting to about 2.6% of the total population of all countries. The data suggest that in 1999, the highest proportion of foreigners relative to the total population was in Switzerland (19.3% with two-thirds of foreign nationals being EU citizens). The greater part of the foreign stock is resident in Western Europe while in Central and Eastern Europe, the proportion is relatively small (less than 2%). Net in-migration in both regions was relatively high in the early 1990s, with the Federal Republic of Germany experiencing the largest absolute increase. In the late 1990s, in some countries in Western Europe, the proportion either declined or stabilised. The percentage of foreigners has been increasing for most countries since 1998 albeit at lower levels for Central and Eastern Europe (the largest numbers have been in the Czech Republic among Central and Eastern European states). For Western Europe, data point to considerable diversity in terms of the origins of foreign migrants and a majority of the foreign national population comes from outside the European Economic Area (EEA) plus Switzerland. Foreign migrants from different regions select different countries as their destination. For example, Africa is an important source of migrants for France while for Spain and Portugal, Latin America is a major region of origin. Asians migrate to different European countries for various reasons; those from the Indian subcontinent usually go to United Kingdom, Filipinos mainly to Italy for temporary employment, and Greece receives immigration from the Middle East region. Germany stands out as the most common destination for nationals of non-EU European countries. Temporary and transit migrants also constitute a substantial population in Central and Eastern Europe.

Figure 2: Stock of foreign population as a percentage of total population in selected Council of Europe countries, 1980-2020

Sources: The estimations are based on data from Council of Europe yearbooks, OECD SOPEMI “Trends in International Migration, 2003”, Salt, J., 2001; “Current Trends in International Migration in Europe”, Council of Europe; Wanner, P., 2002; “Migration Trends in Europe”, European Population Paper Series No. 7. The data draws on foreign stock as a proportion of the total population since those countries with the highest number of foreign residents are not necessarily with the highest proportion of foreign residents.

In Europe, starting from the late 1950s, migrant workers were actively recruited abroad but were not expected to stay in the receiving country permanently. Foreign labour recruitment has formally ceased in Western European countries since the mid-1970s; however, the stock of foreign population has not decreased due to low return rates and family reunification. Many former guest workers have acquired the status of resident non-citizen. This category of people, often referred to as “denizens”, enjoys an intermediate status between citizens and aliens. They are incorporated into various social, economic and legal structures while not enjoying full rights of political participation. Rules for granting “denizenship” and the rights and benefits attached to that status vary from state to state. However, “denizenship” has become a salient and stable feature in all Council of Europe democracies, and has led to reconsideration of who has the right to participate in politics and how.

b) Denizenship and nationality

The continuity between people and place, nationality and demos, is a major premise of modern democracies. EU citizenship is a prominent example of how the boundaries of political membership can be enlarged and the demos can extend beyond national borders. However, even in EU member states, third country nationals are not included in the complementary status of EU citizenship as defined by the Maastricht Treaty. This indicates that so far attempts to expand citizenship rights beyond nationals do not offer a comprehensive framework for attending to issues relevant to the political participation of third country nationals. This invites innovative thinking on the composition of political constituency, citizenship and mechanisms of political participation.

In fact, civil and social rights have also been extended to third country nationals in the EU. Such a trend suggests that citizenship is no longer the exclusive way to access the benefits of state membership and become fully integrated members of a community. Yet, political rights are a prerogative of citizens only. This prerogative is an important one as, for example, the rules for the allocation of social and civic rights are made and altered by those who have and exercise political rights, namely the “native” citizens. This is particularly problematic, for example, in times of economic crises, when citizens and their representatives may decide to cut down social benefits for resident non-citizens, with the latter being excluded from the decision-making process.

However, resident non-citizens contribute substantially to the economic and social development of their country of residence, pay taxes and are expected to abide by its laws. In other words, they share the burdens and benefits of social co-operation. Denying them full political rights appears to violate one of the basic (normative) democratic principle according to which those affected by a certain set of social and political institutions, should also be granted rights that allow them to influence these institutions and their policies. Recognising that the absence of such political rights as a form of democratic deficit, some governments have endorsed various channels of political participation for denizens other than the right to vote. In some Council of Europe countries, denizens are granted opportunities for indirect influence in decision making through government funded organisations, consultative bodies and unions. Such models usually shift the focus of democratic practice from the national level to the local level. By engaging in civic practice at the local level, resident non-citizens come into contact with representative bodies, associations and lobby groups which could also give them a voice at the regional and national levels. Moreover, practice at the local level can result in skills which will enhance participation at national and supranational levels.

Granting denizens political rights, for example the right to elect a representative in municipal elections – as in Ireland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Netherlands, Finland and Luxembourg – introduces a significant change in the terms of political competition. In other words, candidates who win elections have to be accountable to a more diversified constituency, and be responsive to the needs of a sector of the population previously excluded from political life. Moreover, new issues (for example, in the fields of education and health) appear or gain precedence on the political agenda.

Additionally, giving voice to denizens offers an opportunity for dealing with potential ethnic and cultural conflicts through democratic procedures. In this way conflicts are not overlooked, but faced and possibly solved. This would favour a free confrontation of ideas through open dialogue and deliberation, enhancing self-reflectivity and critical multiculturalism in the receiving society.

The fact that this category of migrants is going to reside permanently in the receiving country has been regarded as justifying a project of multicultural citizenship in which political rights can be shared by national and non-nationals.

c) Minorities

Increasingly, some resident non-citizen and sub-state national groups demand collective recognition as well as individual participation in policy processes, for example as “minorities”. Favourable conditions for meeting such claims originate from their considerable numeric presence in some countries, the international conventions supporting minority recognition and the general concern for securing fair access to political, social and economic life for the previously excluded sectors of the population. On the one hand, most Council of Europe countries articulate a common commitment to recognition of group rights and their accommodation (for example, in the countries that emerged from the former Yugoslavia). On the other hand, some (such as France) contest the recognition of these groups as “minorities” and the concession of group rights even when they recognise the equality of people of different cultural and ethnic origin. Some states (such as Croatia) have introduced quotas for linguistic minorities in regional and local representation, while others maintain consultative bodies, that is a second chamber of parliament, or “veto” mechanisms for national or religious “communities”. However, the “smaller” and territorially dispersed members of national minorities, especially the Roma, remain excluded from almost all schemes.

d) Illegal migration

In recent years, illegal migration estimates have reached worrying levels, especially in Southern European countries. Undocumented migrants, officially prohibited from taking up employment, supply a significant proportion of the labour force in the “hidden” or “underground” economy in these countries. Irregular migration is advantageous for employers in the receiving country that profit from undocumented migrants’ lower pay and more flexible and longer working hours. Both the state and the juridical system are absent from this informal sector of the market. The demand for labour supply of the undocumented migrants fosters human trafficking and smuggling, and a dramatic growth in the shadow industries that treat people as commodities in this trade. Every year, thousands of people, especially women and children, fall victim to trafficking for the purposes of sexual or other types of exploitation, which can be equated to a new form of slavery.

Attitudes towards migrants

Observers have pointed out the alarming increase in anti-migrant attitudes in Council of Europe member states. The United Nations World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance has brought this problem into focus, and international organisations such as the International Organisation for Migration, the International Labour Organisation and the European Centre for Racism and Immigration have pointed to a growing negative attitude towards non-EU migrants, reinforced by racial stereotypes diffused through the media and by some political leaders. Data from the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC) show that racially motivated attacks have increased in most EU member states. For some, official statistics indicate a possible reduction of crimes in the last two years. Concerning Central and Eastern European countries, Amnesty International has reported a rise in xenophobic attitudes and racist violence in the late 1990s.

Consistently in all Council of Europe countries, the typical perpetrators of racist crimes are young (18-26) males with low levels of education. However, some NGOs (non-governmental organisations) have reported to the EUMC that worrisome numbers of racist acts of violence are also being committed by law enforcement officers. This suggests that racism finds expression even within the established institutional structures. Extreme right-wing parties – the electoral success of which has risen substantially starting from the 1980s – often appeal to the xenophobic feelings of people in their political campaigns. They also base their electoral strategies on the claim that migrants threaten the national culture and its symbols (such as crucifixes in Italy and Germany), and on a supposed link between unemployment and the number of migrants in their respective countries.

There is no actual empirical or theoretical evidence to support the claim that immigration causes unemployment. To the contrary, some studies show that citizens who are the closest substitutes for immigrant labour do not suffer as a result of increased immigration. Additionally, various studies on demographic trends have identified migration as a possible solution to overcome the “demographic deficit” of Europe and its related problems. It has been argued that in-migration may be a political option to meet the strategic economic and social goals that underpin Europe’s market economy.

A further issue often raised by leaders of xenophobic parties is that immigration constitutes a threat to political and social stability. It is also a commonly spread perception that crime rates have increased as a consequence of immigration. The fear of migrants has been exacerbated by the events of 11 September 2001 and 11 March 2004. Suspicions and fears are especially directed towards migrants coming from the Arab countries and South-East Europe.

These negative perceptions have often been reinforced by the image of migrants portrayed by the media. News programmes report crimes indicating the offenders generically identified as members of a minority group. In a similar vein, several crime fiction programmes characterise murderers and offenders as people of foreign ethnic origin.

At the same time, media represent an important opportunity for the participation and integration of resident non-citizens. Through various mechanisms such as funding multicultural programmes, some countries have highlighted the positive effects that media can have on the perceptions and attitudes of the public, as well as on the self-perception of migrants.

Representation

Political parties

No democracy exists without political parties even if parties differ in organisational structure, ideology, size, functions and goals. They act as an intermediary between voters (citizens) and public authorities (rulers) By structuring the political field they help voters in making their choice and they help rulers put together governments. There exist many definitions of political parties ranging from the very broad to the extremely narrow. Often, definitions are based on one or more of the functions of political parties. The most commonly accepted criterion is that parties should compete in the political arena, try to get their candidates elected and play a role in forming the government. Parties might fulfil a wide variety of functions – although not all parties are engaged in all functions, and certainly not to the same degree. They might play a crucial role in recruiting and selecting the political elite by nominating candidates for elective offices and filling government positions, in forming and sustaining governments, and in policy making. They might also play an integrative role in society by mobilising and providing a collective identity to voters, by aggregating and articulating social interests, and by enhancing the legitimacy of the political system. In addition, they might similarly engage in voter socialisation, issue structuring and/or social representation. However, a party in a democracy cannot represent the whole of the society as the origin of its name pars (part) illustrates well. In order to avoid democratic deficits, parties in democratic systems are expected to be democratic and transparent themselves as well as establishing lasting and regulated relations between party leaders and their membership.

Party membership, size and organisation

Although party membership shows a declining trend in Europe, such a claim fits long-established democracies of Western Europe better than the recently democratised Southern, and Central and Eastern European countries. All Western European countries report a decrease in the number of party members. Countries belonging to the third wave of democratisation display more variation, with some even showing growth (Greece, Hungary, Slovak Republic and Spain). All this suggests that declining membership is a pervasive trend in well-consolidated democracies. This raises concerns over citizens’ participation in public affairs: democracy is in danger if citizens are so apathetic or disillusioned with it that they avoid joining one of its most salient institutions. The less they join parties, the less they are likely to vote, and when they do both, the less governments can be held accountable, the less individual rights can be enforced, and the less individual and group demands can be represented in the policy process. Finally, the more people choose not to be represented in decision making, the less they will recognise the actions of their democratic government as legitimate.

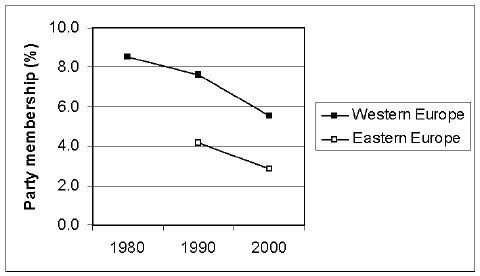

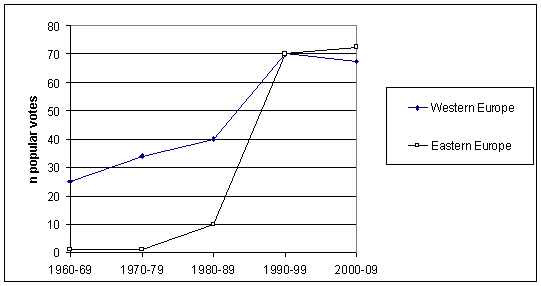

Figure 3: Party membership in Western and Eastern Europe

Source: Figures from Peter Mair and Ingrid van Biezen (2001). “Party membership in twenty

European democracies, 1980-2000”, Party Politics vol. 7, No.1.

However, decline in membership is not always worrying per se. It is not necessarily a sign of declining political participation in general: the decrease in party membership can, at least in part, be accounted for by the appearance of new, more individually appealing and socially acceptable forms of participation (such as signing petitions, boycotting certain products for political reasons, or demonstrating in favour or against a specific policy). Furthermore, the incentive to join parties becomes weaker as parties face various competitors that partially seem to take over the one or the other of their functions while inflicting less demands on and guaranteeing easier access to citizens. Similarly, parties’ demand for members is also waning: the changed nature of campaigning (increase in the use of the media accompanied by a decrease in traditional forms of campaigning that rely on volunteers) and the restructuring of party financing (greater reliance on public funds and, thus, less on member dues) have made it increasingly less important for parties to maintain large memberships. That is, no longer do parties have to provide a “regular or full programme of participatory events” besides those that are directly related to elections. Finally, a large party membership may not make the democratic system more responsive to citizens’ demands: the larger the membership, the smaller its ability to influence party leadership may be.

During the 1990s, scandals involving illicit party financing were frequent throughout Europe. Regardless of political or party system, party organisation or ideological orientation, political corruption related to party financing has become a persistent problem. Despite differing institutional and policy arrangements, almost every European democracy has had serious difficulty in coping with providing sufficient funds to its political parties and ensuring that these funds were equitably distributed.

a) Higher (and growing) party expenditures that outweigh legal revenues

By the 1970s, parties had built up permanent and sizeable bureaucracies. These administrative apparatuses proved to be costly to sustain, especially in non-election years when donations were not as generous. Parallel to this, the importance of national-central offices had come to outweigh that of local party branches, and this brought with it a rise in the need for (expensive) professional expertise.

Election campaigns became more and more expensive. First, campaign techniques changed due to technological advances that made volunteer labour less effective. Not only was the importance of partisan militancy diminished, but its replacement – television, radio and newspaper advertisement – were much more costly and effective in influencing voter behaviour. Second, the increasingly competitive, market-oriented, nature of electoral politics and the tendency for longer campaigns have forced the central organisations of parties to invest more money and professional resources in their effort to catch as many votes as possible, regardless of previous affiliations and class loyalties. The more that parties found it necessary to reach out beyond their traditional supporters, the more expensive each additional vote became.

Moreover, in Europe, parties have historically felt the need to sustain a level of participation in national and, sometimes, regional and local political assemblies, social organisations, study groups, partisan foundations and intellectual academies between elections, and these have had to be financed from party budgets (although sometimes with the help of public subsidies). Although it is difficult to gather reliable data on the amounts involved, in recent decades Western European parties of both the Left and the Right have engaged in supporting “sister” parties or political groups in foreign countries undergoing political liberalisation and democratisation. Again, government funds have often been channelled through party organisations for this purpose, but such trans-national activity has no doubt contributed to professionalising their permanent staffs.

Even if legislation on the legal sources of party finance varies throughout Europe, certain general trends can be observed almost everywhere. The composition and sources of income have changed substantially since the 1970s. Membership dues have become less important for party budgets. First, because of declining membership, parties simply cannot raise as much money from this source. Second, the great increase in the need for money demanded that parties look elsewhere for financial support. And, third, in the new democracies of Southern and Eastern Europe membership dues never gained central importance due, in part, to the historical circumstance of single-party systems with various forms of obligatory contributions and, in part, due to the very timing of their processes of regime change.

Another important source of party income has been donations. These may come from various entities: private individuals, business firms, trade unions and/or associations in civil society. Some domestic donations have been banned or limited by law, but subterfuges have not been difficult to find. In most European countries, donations by foreign governments, parties, firms or individuals have been prohibited, but again unknown amounts still seem to manage to get through the ban, especially, when “kick-backs” from foreign aid contracts and state firms operating abroad are involved. Needless to say, many of the party finance scandals of recent years have originated in this murky and difficult to control area of donations.

Parties have historically earned money from a wide variety of firms that were owned or closely affiliated with them, such as printing plants, newspapers, book publishers, travel agencies, consultancies, planning bureaux, research institutions, recreational societies, sports clubs and, more recently, party foundations. While it is difficult to judge the evolution of the importance of these sources of finance, the impression is that they have declined due either to the break-up of ideological solidarity or to commercial competition. For example, it is doubtful whether any partisan newspaper or publishing house in Europe currently earns a profit which is significant enough to represent an important source of party finance.

Public subsidies to parties have gained greatly in significance since the 1970s. While three decades ago such subsidies were rare, today they are a major source of party income throughout Europe. Legislation in each country determines how these subsidies should be distributed, how they can be spent and how they are supposed to be monitored. They can also be allocated directly in the form of money, indirectly in form of free access to television or other media, or some combination of both.

b) Corruption

Illicit party financing has long been a common phenomenon throughout European democracies, but only recently seems to have become a threat to their legitimacy and a source of decline in public trust. What counts as illegal is determined by national legislation; what is illegal in one country may be quite legal in another. Incomes may be illicit if they come from entities whose contribution is banned by law (such as foreign firms or governments), from organised crime, from individual contributions that exceed legal limits or circumvent the legal requirements for recording. Two time-honoured, if illicit, sources are kickbacks from public contracts and bribes – usually to the incumbent party – in exchange for some favourable policy treatment.

There is no reliable and objective way of evaluating whether, over the past thirty years, parties have become more or less corrupt. The above-mentioned gap between rising demand for funds and limited supply from traditional sources suggests that there is a greater material incentive to resort to inconfessable means of finance than in the past. What does seem clear is that public tolerance for illicit fundraising – even when not tainted by personal fraud or profiteering – has increased. Citizens seem to be applying higher standards of ethical behaviour to their representatives and rulers and they are better informed about corrupt practices, thanks to the Internet and to comparative indicators such as that produced by Transparency International. The media have become more inclined to publicise funding scandals; the judiciary more disposed to prosecute those who engage in such acts; the citizenry more likely to react by punishing even those just suspected of corruption. Regardless of what this implies for the long-term future of democracy, the immediate term consequences are serious. Contemporary regimes in Europe have a serious problem with their “internal political economy”. Democracy costs money – and more money each time its electoral game is played. Its ultimate beneficiaries, the citizens, are less inclined to pay these costs whether through voluntary private contributions or compulsory public subsides. Since parties are still the only known way of structuring both electoral competition and the formation of governments, they cannot simply go bankrupt and disappear – or democracy as we know it would disappear.

c) Parties move away from the civil society and closer to the state

This is the result of many factors, including declining party membership, changing campaign techniques and dependence on the state for financing their growing expenditures. Volunteer work for parties became outdated once parties tried to reach people primarily through television. Also, individual donations as a passive form of participation have been declining. A small number of large donations have tended to replace a large number of small contributions. At the same time, as we have seen above, parties have become increasingly financially dependent on public funds and, in some cases, upon big business firms. The state is crucial, not only because in Europe it has become the major supplier of party funds, but also because the incumbent party or parties that control it can gain access to other (often illicit) sources of revenue. On the one hand, the advantage of incumbency has been rising and, hence, the likelihood of oligarchy; on the other hand, all parties have become increasingly under-funded and, hence, the prospect of irrelevance and fragmentation when none of them succeeds in connecting with its targeted public.

d) Citizen disaffection from and apathy towards politics

The problem is not simply that the participation of people in the life of parties has been declining (other forms of political participation may replace this) or that private donations are decreasing (other sources, especially public ones, have been increasing). Cynicism about the motives and practices of politicians has increased to the extent that a large proportion of the population considers political corruption to be “business as usual”.

* * *

These problems are only in part endogenous to “real-existing” democracies. They are also closely connected to the exogenous challenges and opportunities outlined in Part I.

Globalisation and its consequences pose one of the biggest challenges for parties in Europe. First, trade liberalisation meant that money could move more and more freely across national borders which widened the range of potential sources of financial support for parties and this proved to be vital for the opposition in post-communist countries struggling for democracy in Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. It also poses a dilemma for those established national democracies, however, which try to resist the influx of foreign funds into their domestic elections and policy processes. Second, the concentration of money that globalisation places in the hands of multinational corporations and wealthy individuals could make it easier for parties to raise money. However, this would make these parties more vulnerable to the accusation that they have become excessively dependent upon business interests. To the extent that this occurs across the political spectrum, it reinforces the popular notion that “all parties are alike” and, hence, that choosing among them is a futile exercise.

European integration poses a very similar challenge. The tendency to integrate markets, professions and policies on a regional scale blatantly contradicts one of the central premises of existing party systems, namely, that they are responsible for organising political competition on the basis of a sovereign territorial unit, the national state. For example, people living and working in a country different from that of their citizenship are often prohibited from financially supporting parties in the state in which they reside, while firms incorporated in any EU member state, but foreign owned, are free to make partisan donations.

Technological changes have literally revolutionised campaigning and, in some countries, are beginning to affect fundraising. Television has firmly established itself as the major medium for addressing the general public during elections. Depending on the mix of private and public channels and on the content of licensing arrangements, this has greatly increased the financial cost of campaigning and depreciated the importance of voluntary contributions of labour by party members. It has also enhanced the focus on the personality of candidates at the expense of the appeal of party platforms, since that is what is best projected by this exceedingly time-dependent form of mass communication.

It is too early to assess whether information and communication technology (ICT), in particular the Internet, will provoke an analogous revolution. The Internet seems to have the potential for reversing the trend towards exploding costs and, therefore, for evening out the conditions of competition between large and small, poorly and well-endowed parties. And there are strong indications that parties are experimenting extensively with this medium to reach actual members, potential donors and eventual voters. No party today can afford to be without its website. But this is also the case for individual candidates and elected representatives. Will this rapidly expanding form of direct communication (and, eventually, of electronic voting) have the effect of further undermining traditional forms of party organisation and affiliation?

A sense of insecurity probably has a significant, but indirect effect upon partisan organisation and activity. As we have seen above, the increased demand for money (and decreased supply of it from members) makes parties vulnerable to engaging in corrupt practices and this can enhance the influence of organised crime as a potential source for the missing funds. Indeed, some techniques of illicit party financing closely resemble those of money laundering and some of the means for soliciting contributions are hardly distinguishable from racketeering or extortion. Again, to the extent that all or a wide range of parties resort to this source of clandestine funding, this will reinforce the already existing tendency to condemn parties as such as intrinsically corrupt and incapable of combating organised crime.

No one can accurately judge the extent to which external sources of insecurity, hostile states and threatening non-states are influencing the behaviour and status of political parties in Europe. In the not-so-distant past, clandestine “contributions” by the Soviet Union were used to discredit national Communist Parties, just as happened in the interwar period with Fascist and National Socialist “transfers” across borders. In the contemporary context, trans-national financing of partisan and civil society organisations in democratising countries has become an openly recognised practice which does not seem to have brought discredit upon the recipients. Money circulating in the opposite direction, that is from autocratic governments to parties in democratic polities, is quite another matter. The “War on Terrorism” and “the War on Drugs” have focused a great deal of attention on international traffic in clandestine funding, but so far European political parties have been spared any embarrassing revelations.

A European party system: an excursus

European political parties could potentially offer a response to the declining autonomy of the national state and the parallel decline in membership in its political parties. The development of a genuine party system among EU member states would constitute an important step towards creating a European demos, with its distinctive citizenry and electorate. These parties would be unlikely to replace well-established national parties for the foreseeable future, given the asymmetry that persists between the importance and the functions of national parliaments and the European Parliament (EP) – not to mention the intrinsic difficulties in creating partisan identities on such an extensive scale for such a linguistically and culturally heterogeneous population.

The shift of economic and political competencies from the national to the European level has (so far) not been matched by a corresponding shift in democratic legitimacy. EU institutions lack the legitimacy of their national counterparts and the gap between EU citizens and European institutions seems to be growing. Public opinion surveys tell us that many people see the Union’s institutions as remote, bureaucratic and undemocratic. This democratic deficit is aggravated by national politicians who tend to use the European Union as a scapegoat, and fail to explain their own role in adopting European legislation. The resulting lack of a European demos is aptly demonstrated by the large discrepancy between the turnout for national and European parliamentary elections.

The existence of a European demos would first require an increase in the salience of European (as opposed to national) political issues. Sandwiched between the traditional distinction between domestic and foreign policies, the significance of the emerging regional dimension has not been communicated strongly enough to those affected by it. Europeans, if they were aware of how many of the issues that formerly belonged in the category of domestic politics have been shifted to the regional level, might be more inclined to combine across national borders to found and fund genuinely trans-national political parties. As it stands, they are vaguely aware that their interests are structured in European elections and within the European Parliament by “federations” of national parties that have no common platform. This merely aggregates and reproduces in a superficial fashion the different cleavages that emerged historically within each member state, rather than recognise and reflect the cleavages that transcend these national borders.

One reason for this lack of genuine European parties is related to the way that elections for the European Parliament are conducted. They are not organised on a uniform basis across member states. Although in the latest ones all countries have used roughly the same system of proportional representation, the rules for assignment of seats and definition of constituencies are still quite divergent. The elections are not held on the same day, and in some cases they do or do not coincide with local, municipal or provincial contests. The result is what has been called “second-order elections” in which the ostensible purpose is to choose representatives to the European Parliament where they will have to deal with European issues, but the actual process reflects the standing issues within each national state. Euro-citizens, needless to say, are aware of this and use these elections primarily to send a message to their national rulers – often one of discontent, since they can afford to vote for more extreme candidates and parties, knowing that they will not be governed by them. This has produced the embarrassing outcome that incumbent governments and centrist opposition parties tend to fare badly – which can have serious implications for the stability of domestic politics. Another increasingly embarrassing aspect of European-level elections is that they have been characterised by a markedly lower level of voter turnout than national ones. Each successive contest since 1979 has attracted proportionately less voters. This has been the case in virtually every member state, despite the fact that the effective powers of the European Parliament have manifestly increased during the same period.

The political groups within the European Parliament do not and cannot function as European parties. Not only is their composition heterogeneous – the parties from different member states can be very different in social composition and programme even when collected under the same label – but they also have no effective organisational infrastructure. For example, they have little or no role in the selection of candidates for EP elections. Their financing has long been a mysterious matter due to lack of transparency and insufficient monitoring. Expenditures are left exclusively in the hands of national parties that receive subsidies directly from the European Parliament to cover the costs of campaigning. These parties have virtually no incentive to focus on distinctively European issues and, as we have noted above, base their campaign efforts primarily around national ones.

Civil society

Virtually all students of contemporary democracy recognise that the presence of a viable and lively civil society “pressuring” authorities to pay attention to rights, entitlements, interests and causes contributes positively to both the persistence and the quality of modern democracy – and not just in Europe and America. Nota bene that civil society contributes to –but does not itself cause this outcome. It cannot unilaterally bring about democracy. Nor can it alone sustain or improve democratic processes once they are in place. As we shall see, civil society acts along with other institutions and practices – participation by individual citizens, competition between political parties, the legislative process, regular and fair elections for major offices, checks-and-balances between governing bodies, a free and diverse press, autonomous local and provincial governments, the rule of law and an independent judiciary – just to name the most obvious ones.

Before proceeding to an analysis of the present state of civil society in Europe, let us first define it. Civil society is a set or system of self-organised intermediary groups that: (1) are relatively independent of both public authorities and private units of production and reproduction, that is of firms and families; (2) are capable of deliberating about and taking collective actions in defence or promotion of their interests or passions; (3) but do not seek to replace either state agents or private (re)producers or to accept responsibility for governing the polity as a whole; (4) but do, however, agree to act within pre-established rules of a “civil”, meaning mutually respectful and public, nature.

The multiple and varied units of such a civil society may limit themselves by seeking to influence and not to replace elected officials, and by accepting to treat each other respectfully, but their presence in political life is not an unmitigated blessing. In other words, the mere presence of such a mixture of self-regarding interest associations and other-regarding social movements can produce both “public goods” and “public bads”. The European (and American) experience over the long run suggests, however, that the positive effects of civil society far outweigh the negative ones. What interests us is whether, given the challenges and opportunities facing the contemporary societies of Western and Eastern Europe, this will prevail in the future.

The most obvious obstacle to assessing changes in the role of civil society is the continually changing nature of the subject itself. Unlike abstention in elections or public trust in institutions, or shifts in electoral preferences or increases in the number of referendums, when it comes to civil society, the interest associations, social movements and charitable foundations that compose it do not remain fixed in either form or function. With the exception of those organisations whose membership is compulsory and whose interest domain is determined by public law, for example professional “orders”, sectoral “chambers” and some trade associations and unions, most of its units are free to choose whom they wish to represent and how they interpret their mission. This means that their material resources and organisational status are continually at the mercy of shifts in social structure, consumer preference and political purpose. Forms of association that previously played an important, even a crucial, role in political life may gradually decline – hopefully, to be replaced by other kinds of autonomous collective action. For example, an American social scientist drew dramatic negative conclusions – “there is reason to suspect that some fundamental social and cultural preconditions for effective democracy may have been eroded in recent decades” (Putnam and Goss, 2002, p.3) – from the tendency of his concitoyens to “bowl alone”, while ignoring their propensity to seek out and use other means of socialising with each other and articulating politically their shared interests and passions.

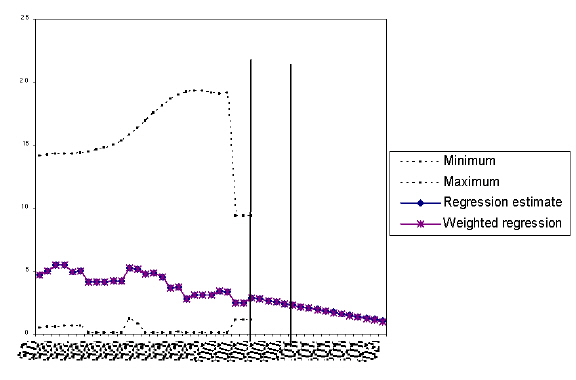

Figure 4: Union density (% of economically active population) in Europe, moving average

Source: Eurobarometer and World Value Survey (1995-97)

Let us first take the case of trade unions. There is no question that this form of collective action has had a continual and significant impact on the democratisation of European polities and subsequently upon their everyday politics. Trade unions struggled to enfranchise their members and workers in general and mobilised periodically to ensure that the benefits of public policy would be more equally distributed among citizens. No national history of civil society could possibly ignore them, or the wider democratic effect that they had upon other political parties, interest organisations and social movements.

Figure 4 above displays data on the long-term evolution of membership in trade unions as a percentage of the economically active population in Europe since 1972. All observations have been “smoothed out” by using three-year moving averages and “normalised” to reflect the differing size of countries and the changing composition of the Council of Europe’s membership. According to two alternative progressions (one linear, the other weighted by time), the density of union membership (which was 28% in 2001-4) will be c. 25% in 2010-12 and c. 22% in 2018-20, provided that the underlying socio-economic trends persist and no major changes in public policy intervene. If we take into consideration only those countries for which we have data and that were members of the Council of Europe in early 1970, the picture does not change very much. The trend is still relatively stable and membership density in 2018-20 is projected to be 23% rather than 22% of the economically active population. Comparable data for trade unions in Central and Eastern Europe and the republics of the former Soviet Union are not available, but those that do exist suggest that membership density fits within the previously established trend lines, although at the lower range of variation.

Despite alarming voices predicting the disappearance of the organised working class (or its suffocation by non-unionised workers from the East), our conclusion is more re-assuring, especially when one takes into consideration changes in the sectoral composition of employment (the relative decline of manufacturing where unionisation has historically been greater), the shifting balance of men and women in the active workforce (the former have been easier to recruit than the latter) and the growing proportion of part-time workers (ibidem). For example, the density of trade union membership in the United States fell much more dramatically – from 45% in 1970 to 18% to 1995. Nevertheless, the conclusion seems inescapable that one of the most significant and stable categories of associability within European civil societies will diminish in relative importance – but certainly not “fade away”.

Figure 4 also illustrates a second trend. At the initiation of the time series (c. 1972), the disparity in national densities of trade union membership was of the order of 48 points, from a high of 68% to a low of 20%. Thanks largely to the entry of the Southern European countries into the Council of Europe, this disparity has widened considerably. The most unionised polity had 87% in 2003; the least had 10% – a 77 point difference. Whether this is a temporary “diversion” due to the recent nature of democratisation and, with it, the sudden diffusion of freedoms of association, assembly, speech and petition after a long period of repression by single-party rule, or whether this represents a more deeply entrenched tendency towards “free-riding” and even hostility in neo-democracies to forms of collective action based on class and sectoral interest, is not yet clear. What is clear is that, if it should be the declared policy of the Council of Europe to promote greater convergence over time in the qualities of the respective civil societies of its member states and, moreover, if this convergence should be towards a higher level of performance, this will require a good deal of reform effort.

A third trend among trade unions – more difficult to document – seems to be towards a decrease in their number at each level of aggregation (largely, through mergers) and an increase in the proportion of specialised associations that are members of higher-order federations and confederations. In short, the trade union movement seems to be undergoing a process of organisational consolidation through which its base units are becoming larger in their members and more comprehensive in their scope of representation.

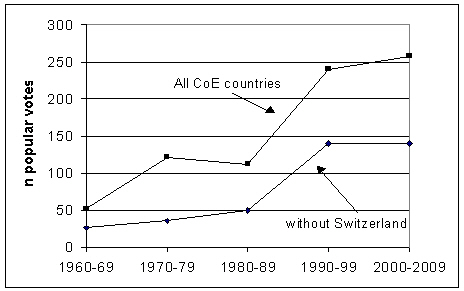

Figure 5: Membership in voluntary associations in Europe, moving average (in %)

Source: Eurobarometer and World Value Survey (1995-97)

So far, we have made the mistake of presuming that the evolution of membership and organisational structure in a single type of association was somehow emblematic of civil society as a whole. Granted that trade unions have historically been of a much greater significance for democracy than, say, bowling societies, it is nevertheless perfectly plausible that other types of associability have been following different patterns. Now, we are about to commit the inverse fallacy, namely to assume that all memberships in voluntary associations are of equal significance. Thanks to the regular surveys carried out by Eurobarometer since 1977 and the World Values Survey of 1995-57, data are available on the proportion of a random sample of the population in twenty-eight countries that report belonging to at least one association. They are displayed in Figure 5 above according to three-year moving averages beginning in 1975. The two points of inflection (1975-77 and 1995-97) again reflect major changes in Council of Europe membership (first, southward and, then, eastward), and in both cases they depress the proportion of those claiming to belong to an association. The summary figure for Europe as a whole (weighted by size of country) is 47% and both the linear and time-weighted projections would be in 2010, 48% (linear) and 46% (weighted) and in 2020, 48% (linear) and 45% (weighted) – ceteris paribus. If one includes only those countries already members in 1972, the corresponding figures are 50% (2003), 55% (2010) and 57% (2020). The “spread” between best and worst performers was 47 points in 1975 and an astonishing 72 points in 2003, if all countries are included, and 46 points in 1975 and 61 points in 2003, if only the 18 original member states are included.

This time the evidence is less preoccupying. Democratisation, Southern and Eastern, seems to have had some downward impact on “primary associability” in Europe, but the overall impression is one of exceptional stability. If nothing changes, those persons in Western Europe who are members of at least one association will even be marginally higher in 2020 than in 2003. Their eastern brothers and sisters may be less “associative”, but their net effect will depress the total by only two or three percentage points.

Let us now take a second look at this same data set by selecting out and distinguishing grosso modo between two types of organisations: first, those that directly provide services and satisfactions to their members (social); and second, those that are more likely to make demands upon authorities that indirectly benefit their members and the public at large (political). In the first, we find groups that provide social welfare, personal health, education, art, music and cultural appreciation, youth, sports, recreation and entertainment. In the second, we have included trade unions, professional associations, local community groups, political parties, movements for human rights, peace, Third World development, resource conservation, environmental protection, gender equality and so forth. At the beginning of our time-series (1974), ostensibly political organisations were proportionately slightly more important (55.0% of the European population reported membership in at least one of them) than social ones (51.2%). By our last observation (2003), the former had declined much more rapidly (to 33.2%) when compared with the latter (39.5%). According to our projections, only 22.8% of Europeans in 2010 and 13.7% in 2020 will be members of any type of political association or movement – again, ceteris paribus. Now, a lot can change during that period. We have reason to believe that participation in such organisations did increase markedly during the 1950s and 1960s, which suggests that some cyclical process may be at work within civil society. But what will provide the incentive for such a turn-around in the future? Our analysis below has failed to detect any “natural” process external to democracy that seems likely to do this. Only conscious and consequent reforms in its internal rules and practices can provide the necessary incentives.

Volunteering to work in an association is not the same thing as being a member of one. It is possible, therefore, that fewer people could be joining and more people could be working in various parties, associations and movements. The data on such “volunteering” is sporadic and subject to wide variations due to seemingly minor changes in the wording of survey questions, but they do point to a gradual increase in most of the countries in Western Europe between 1981 and 1999. Comparable data for Eastern Europe, even for a shorter time period, do not exist. However, no one would be surprised if they showed marked lower levels given the turmoil that has accompanied regime change there.

And now we come to an interesting paradox. Although the data are scattered and difficult to interpret comparatively, they indicate no tendency towards a decrease in the sheer number of associations, movements, societies and foundations. The decline in the proportion of the population reporting membership in at least one of them does not seem to be discouraging “organisational entrepreneurs” from trying to create new units of civil society. Granted that we lack reliable information on those organisations that fail and disappear, but the clear impression is one of net growth in virtually every European society. This suggests that the universe is becoming increasingly specialised. More and more associations, movements and foundations are chasing after members and funds to support ever more specific definitions of collective interest and passion.

And, as we have noted above with regard to trade unions, there is reason to believe that “traditional” organisations representing the interests of social classes, economic sectors and professional specialisations are merging and therefore decreasing in number. The dynamism, therefore, can only be coming from entrepreneurs appealing to new interests and passions – mostly, we suspect, recreational, cultural, educational and social-service oriented, but also including a wide variety of “causes” – environmentalism, human and animal rights, feminism, anti-globalism and democracy itself. It is difficult to document this shift to “new social movements” since their very nature often precludes an accurate count of their numbers or their members. Nevertheless, the increase in “unconventional” collective action by these movements – protests, petitions, boycotts and demonstrations – has become manifest and has transcended the boundaries of national polities. What is much less obvious is the relation of this activity to more traditional forms of democratic participation: voting, party identification, union membership and civic associability. Nor is it clear whether the young people who form the overwhelming bulk of participants in these network forms of organisation will eventually settle down and join the same parties and associations as their parents.

Analytical overview

As one might have expected from its intrinsic variability and constant adaptability, civil society has probably been affected more than any other aspect of democracy by all of the unprecedented challenges and opportunities discussed in Part I. Every one of them seems to be having some impact on either the membership of associations, their composition, their number, their scope or their resource base.

Globalisation. Here, the major difference has been the spread of trans-national non-governmental organisations, especially those advocating a wide range of causes from democracy and human rights to environmental and gender issues. The impact has been particularly great in the new democracies to the East where the relative importance of financial resources and conceptions of passion and interest has been more disproportionate. In the more established Western democracies, the focus of these NGOs has often been on globalisation itself and its economic, social and environmental impact upon an increasingly well-educated citizenry sensitive to the dilemmas of “complex interdependence”. There is hardly a government in Europe that has not had to face pressure from organisations whose human and material resources come from beyond their borders and whose networks of influence penetrate deeply into what had previously been a relatively autonomous realm of national politics. Whether this narrows the range of policy responses, or widens the potential resources that can be brought to bear on such complex issues, remains to be determined – but the outcome will have a significant effect on the effectiveness and legitimacy of rulers at both the national and the supranational levels.

European integration. EU directives and regulations have affected the civil societies of member, candidate and adjacent states and even led to the emergence of an embryonic European civil society. Again, the greatest impact has been on the neo-democracies to the East, especially those struggling to meet the obligations of the acquis communautaire and competing for funds from the various EU programmes. In a few policy areas, such as agriculture and regional funds, exerting influence at the European level has become imperative, whereas in most cases, associations and movements tend to work through their respective national authorities. EU policies have also opened up unprecedented opportunities for direct access to large trans-national enterprises. The overall picture is, therefore, mixed: pluralism for specialised functional interests and selected causes through a proliferation of points of access in this emerging “multilevel” and “polycentric” polity and corporatism for those at the supra- and national levels with privileged resources or special access to specific agencies. Particularly striking has been the re-emergence of national systems of policy concertation in response to the twin challenges of a single European market and monetary unification.