The use of migrant detention across Europe, whether for the purpose of stopping asylum seekers and other migrants entering a country or for removing them, has long been a serious human rights concern. I have repeatedly spoken out against the pan-European trend of criminalisation of asylum seekers and migrants, of which detention is a key part. Detention is a far-reaching interference with migrants’ right to liberty. Experts have confirmed its very harmful effects on the mental health of migrants, especially children, who often experience detention as shocking, and even traumatising.

For this reason, it is imperative that states work towards the abolition of migrant detention. This does not mean giving up on managing one’s borders, including decisions over who enters a country and who can stay. It means investing in alternative measures to manage migration effectively, which are not as far-reaching and harmful as detention. Thanks to the important work of civil society organisations, national human rights structures, the EU Fundamental Rights Agency, the UN and the Council of Europe, the past few years have seen an upsurge in discussions about alternatives to immigration detention.

However, states’ reactions to the increased arrival of migrants in Europe are threatening past progress. One of the first actions taken under the 2016 EU-Turkey statement was to close off several reception facilities (“hotspots”) on the Greek islands with fences, effectively making them detention centres – a practice which has been partially reversed since then. This month, the Hungarian government said it would make preparations to urgently reinstate mandatory migration detention. In Italy, plans to open sixteen new detention centres were reported. While European states increasingly feel the need to control – and to be seen to control – their borders, this cannot mean falling back on detention as a knee-jerk reaction.

The legal and policy imperatives for alternatives to detention

The European Court of Human Rights has repeatedly stated that states applying immigration detention should not only have a proper basis for this in domestic law, but that it must also be necessary in the particular circumstances of the case. Recently in Khlaifia and others v. Italy the Court stressed that detention is such a serious measure that it is only justified where other, less severe measures have been considered and found to be insufficient. In 2010, the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly adopted a resolution calling on states to ensure that “the detention of asylum seekers and irregular migrants shall be exceptional and only used after first reviewing all other alternatives and finding that there is no effective alternative.”

Importantly, governments have themselves acknowledged the need for alternatives. The Committee of Ministers’ Twenty Guidelines on Forced Return only allow detention if “non-custodial measures such as supervision systems, the requirement to report regularly to the authorities, bail or other guarantee systems” are found to be ineffective. The 2016 New York Declaration for Migrants and Refugees, adopted by heads of state and government, also commits states to pursuing alternatives. During my own visits to many states, such as Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, I have urged governments to include clear alternatives to detention in their legal and policy frameworks.

While there is a need to expand and improve alternatives for all persons involved in immigration proceedings, this is particularly the case for vulnerable persons, including children. For migrant children, detention is not only subject to the requirements mentioned above, but also to an assessment of the best interest of the child, as set out in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. It has been my position, however, that there are no circumstances in which the detention of a child for immigration purposes, whether unaccompanied or with family, could be in the child’s best interest. For this reason, the complete abolition of the detention of migrant children should be a priority for all states.

Alternatives are not only an essential tool in safeguarding the human rights of migrants. They are also helpful for states. If properly implemented, they can help build trust, communication and engagement between the migrant and the state in return procedures, which can actually increase their effectiveness. Also, detention is very costly. Alternatives can provide significant savings, especially now that some states are faced with increasing numbers of new arrivals. Money saved on expanding detention could be more usefully directed towards improving protection systems, reception conditions and, importantly, the long-term integration of those who are allowed to stay.

Making alternatives a reality

Even when states have set up alternatives, these are often ad hoc or open only under very stringent circumstances. It is important that states strive to make alternatives open to as broad a group of migrants as possible. Furthermore, having only one type of alternative, such as bail, is not sufficient. Each person has their own particular circumstances and needs, which have to be accommodated to some extent to ensure that detention is not necessary. A number of extensive reports on the various alternatives that are applied in member states, their effectiveness and their potential drawbacks have been published over the last couple of years, including by the EU Fundamental Rights Agency, academics and civil society networks. This gives states plenty of information to develop a well-stocked toolbox of alternatives, varying also in degrees of restrictiveness, if any restrictions are necessary.

Coaching and case management should always be part of this toolbox. Sometimes, this can be sufficient to keep track of migrants and render detention unnecessary. But they should also be integral components of non-detention measures that impose restrictions, such as regular reporting requirements, financial guarantees or limitations on freedom of movement. In addition, states should ensure that applying an alternative does not simply mean letting migrants fend for themselves. States should ensure they can meet their basic needs. This ensures the protection of their human dignity and also encourages positive engagement with the authorities.

Care must also be taken so that states do not simply make a trade-off between detention conditions and alternatives to detention. Although there is a crucial need to improve the conditions in detention facilities in many European states, governments should not simply deflect calls for avoiding detention by referring to improvements made in detention conditions. This is particularly important when it comes to children. Both the Belgian and the Dutch governments, for example, have committed to setting up better, more ‘child-friendly’ detention facilities. While this will possibly reduce some of the hardship faced by children in detention, this cannot be seen as a substitute for categorically prohibiting the detention of children.

Finally, states should ensure that alternatives are applied to all forms of detention. In France, for example, I found that adults deprived of their liberty in airport zones cannot access alternatives. Furthermore, across Europe, there is an increasing blurring of lines between ‘reception’ and ‘detention’ facilities. I already mentioned the “hotspots” in Greece. In the above-mentioned Khlaifia case against Italy, the Court made very clear that what is determinative of ‘detention’ is whether people are deprived of their liberty, irrespective of the name of the facility where this happens.

The way forward

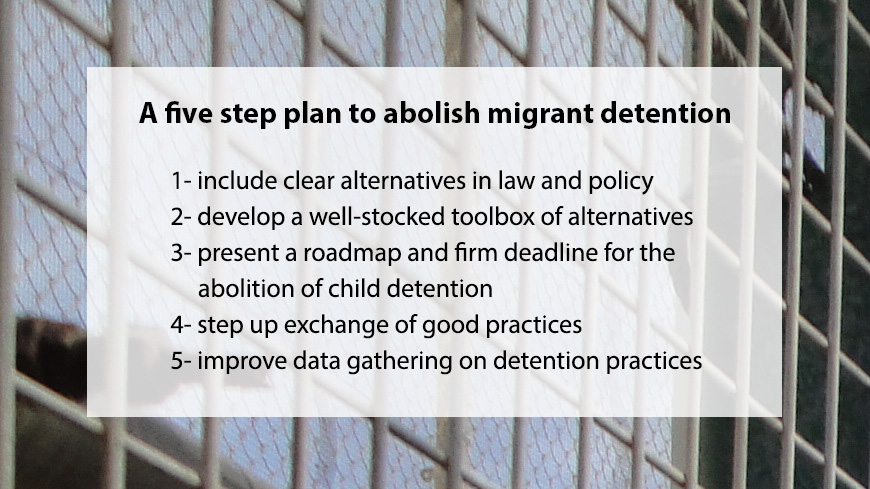

European states urgently need to step up their work on reducing migrant detention and developing effective alternatives.

A first and crucial step now is that all states ensure that the obligation to provide sufficient alternatives is set out clearly and effectively in domestic law and policy, and that the use of alternatives is always assessed prior to any decision to detain.

Secondly, this should be complemented by setting up comprehensive programmes of viable and accessible alternatives, catering to a range of different needs and circumstances; the well-stocked toolbox I mentioned. Individual case management and coaching should be an integral part of each of these alternatives, as well as assurances that basic needs can be met.

Thirdly, there is a need for a clear path to the abolition of child detention. So far few governments have been willing to follow this path. It is therefore of the utmost importance that all involved, in particular parliamentarians, national human rights structures and domestic civil society organisations, call upon their governments to present roadmaps, including a firm deadline, for the abolition of child detention.

Fourthly, European states should exchange good practices among themselves and with other actors much more systematically. There is no doubt that states often look for each other’s guidance in amending their migration policies. Member states should make full use of the opportunities that international fora, such as the Council of Europe, offer to bring together knowledge, to learn from each other as well as from civil society organizations, and to improve the protection of asylum seekers and migrants.

Last but not least, there is a distinct lack of data that needs to be addressed. A 2015 expert report illustrates the lack of consistent data gathering on detention practices. If we are to have honest discussions of what works, for migrants and states, sufficient data need to be available about people deprived of their liberty, the situations in which they are offered alternatives, and the outcomes of these processes. This would improve policy making and enhance necessary human rights monitoring.

Nils Muižnieks

Useful links:

- Commissioner’s webpage on the human rights of immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers

- European Court of Human Rights, Factsheet on the detention of migrants, 2016

- Council of Europe Committee of Ministers, Twenty Guidelines on Forced Return, 2005

- Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly, Resolution 1707(2010) on the detention of asylum seekers and irregular migrants in Europe, 2010

- Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly, webpage on its Campaign to End the Immigration Detention of Children

- Global Campaign to End Child Detention’s website

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, webpage on detention of asylum seekers

- International Detention Coalition, ‘There are alternatives: a handbook for preventing unnecessary immigration detention’ (revised edition), 2015

- EU Fundamental Rights Agency, ‘Alternatives to detention for asylum seekers and people in return procedures’, 2015