Culture and Sport

Young people generally are often portrayed as being full of ambitions and hopes for the world and, therefore, important drivers of cultural change. The United Nations Population Fund describes well this expectation on young people as shapers of the culture of the future:

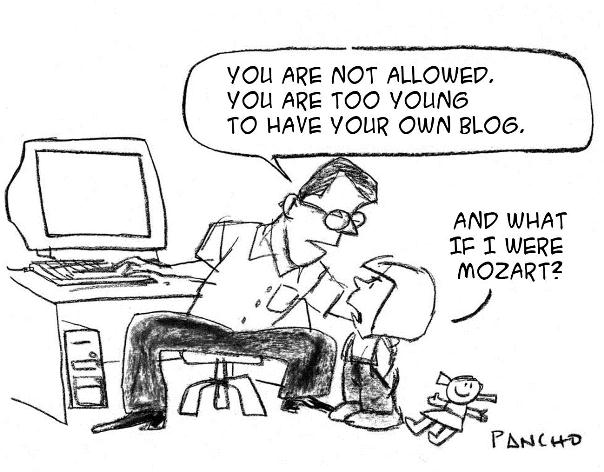

As they grow through adolescence, young people develop their identity and become autonomous individuals. Young people do not share their elders’ experiences and memories. They develop their own ways of perceiving, appreciating, classifying and distinguishing issues, and the codes, symbols and language in which to express them. Young people’s responses to the changing world, and their unique ways of explaining and communicating their experience, can help transform their cultures and ready their societies to meet new challenges. … Their dynamism can change some of the archaic and harmful aspects of their cultures that older generations take to be immutable.1

Sport is a universal element in all cultures and therefore we have chosen to include it as a theme for Compass. Sport is popular particularly with young people; statistics show that 61% of young people aged between 15 and 24 participate regularly (at least once a week) in sporting activities in the EU22. Another reason for including sport is that sports provide young people with opportunities for social interaction through which they can develop the knowledge, skills and attitudes necessary for their full participation in civil society.

Culture and sport are both human rights and related to various other human rights. They are also the grounds on which human rights are often challenged and abused, including those of young people.

What do we mean by “culture”?

The word “culture” is used in many different ways, for instance, popular culture, mass culture, urban culture, feminist culture, minority culture, corporate culture and, last but not least, youth culture. We can also talk about a cultured person, meaning someone who has good manners and is formally educated in the traditions of literature and art, or about culture shock: a person’s disorientation and frustration when experiencing an unfamiliar culture. None of these meanings of “culture” is usually dealt with by ministries of culture or their equivalent governmental authorities.

The word “culture” comes from the Latin, “cultura” meaning “to tend, guard, cultivate, till”. It was first around 1500 CE that the word started to appear in the figurative sense of “cultivation through education” and it was only in the mid-19th century that the word was linked to ideas about the collective customs and ways of life of different societies.4 It is this meaning of culture as inherited patterns of shared meanings and common understandings that we address in this section.

No culture is homogenous. Within each culture, it is possible to identify “subcultures”: groups of people with distinctive sets of practices and behaviours that set them apart from the larger culture and from other subcultures. Culture is as difficult to define as it is to seize; cultures are ever evolving and changing. To paraphrase Heraclitus about not stepping twice in the same river, the culture in which we communicate today is not the same in which we communicated yesterday. Yet, in our eyes and perceptions, it is truly the same.

Question: What new ideas or technologies have changed your culture in the last ten years?

The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights defines culture as follows:

Culture […] encompasses, inter alia, ways of life, language, oral and written literature, music and song, non-verbal communication, religion or belief systems, rites and ceremonies, sport and games, methods of production or technology, natural and man-made environments, food, clothing and shelter and the arts, customs and traditions through which individuals, groups of individuals and communities express their humanity and the meaning they give to their existence, and build their world view representing their encounter with the external forces affecting their lives.5

Some aspects of culture are highly visible, for instance the way people dress. Other aspects are mostly unconscious, almost instinctive. One way of thinking about culture is to use the metaphor of an iceberg. An iceberg has a visible part above the waterline and a larger, invisible section below. In the same way, culture has some aspects that can be observed and of which we are conscious and other aspects that can only be suspected or imagined and reached through dialogue and introspection. Just as the root of the iceberg is much larger than the upper part, so is the greater part of culture “invisible”. The risk is to take the part for the whole. By focusing on what is visible to us (and that we seem to “understand”) we risk missing the essential in the persons, in the human beings.

If you understood everything

I said, you’d be me.

Miles Davis

Question: What aspects of your culture are, in your understanding, invisible to others?

Culture is also the lens through which we view and interpret life and society. Culture is passed over from one generation to the next one, while incorporating new elements and discarding others. Because we have taken so much of the prevailing culture in with our mother’s milk it is very hard to view our own culture objectively; it just seems to be normal and natural that our own culture feels “right” and other cultures with their different ways of thinking and doing seem unusual – maybe even wrong.

Culture is also explained as a dynamic construct made by people themselves in response to their needs. Consider for a moment the arctic environment of northern Sweden; people there face different challenges from people living on the warm shores of the Mediterranean; consequently they have developed different responses – different ways of life – cultures.

Today, as a result of modern technology and globalisation, the two cultures have more in common than they did in the past, but nonetheless they still have many differences, including different notions of what it means to be European.

Who we are or believe we are depends to a large extent on the cultures we grow up in, are exposed to or decided to embrace. Each of us, however, is also unique. It is the accident of where we are born that initially defines, for example, the languages we first learn to speak, the food we like best and the religion we follow, or not. Identity, like culture, is a complex concept with parts above and below the line of consciousness that change with time and location. We can talk about personal identity, gender identity, national, cultural, ethnical, class or familial identity, and in fact about any other sort of identity. Accepting that identity is intricate, diverse and dynamic and about being oneself, and at the same time recognising and accepting others’ rights to express their own identities is essential to building a culture of human rights, where everyone is due equal rights and respect. Identity is what makes each of us unique. However, this uniqueness is not the same throughout our lives; it is ever changing.

Culture in contemporary societies is a site of controversy and struggle over identity, belonging, legitimacy and entitlement..6

What do we mean by “sport”?

“Sport” means all forms of physical activity which, through casual or organised participation,

aim at expressing or improving physical fitness and mental well-being, forming social relationships or obtaining results in competition at all levels.7

European Sports Charter

Sports, and especially team games, are an important part of our lives, whether we are spectators or participants. For many, football is a never-ending source of conversation, fans feel a deep affinity with their team, and star players are given the status of heroes. The current fashion for people to want to look good, youthful, athletic and healthy is manifested by the number of fitness clubs opening up and the quantity of magazines published about slimming, while parks are filled with joggers. Other activities which involve mental rather than physical exertion, such as chess, are also considered sports. There are sports to suit all tastes and temperaments and thus sport can truly be closely linked to our identity and culture at some point in our life.

If we look deeper into the underlying value and purpose of sports and games – and this includes the play of young children – it becomes apparent that all sports, whether football, spear throwing or yoga, have developed as a means of teaching necessary life skills, which is why sports are seen as an important part of the educational curriculum, both formal and non-formal.

Cultural rights

Cultural rights were first enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 27:

Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.

Protecting and promoting cultural rights is important to the process of empowering individuals and communities. Having their cultural rights recognised helps communities to build their self-esteem and to be motivated to maintain their traditions while being respected for their practices and values.

The term “culture” is not clearly defined in human rights law. The protection of culture in human rights law encompasses two concepts. Firstly, the

right of people to practise and continue shared traditions and activities. Secondly, the protection

of culture in international law covers the scientific, literary and artistic pursuits of society.8

According to the Human Rights Education Associates, the right to culture in human rights law is essentially about the celebration and protection of humankind’s creativity and traditions. The right of an individual to enjoy culture and to advance culture and science without interference from the state is a human right. Under international human rights law governments also have an obligation to promote and conserve cultural activities and artefacts, particularly those of universal value. Culture is overwhelmingly applauded as positive in the vast majority of human rights instruments. The right to culture includes a variety of components:

• the right to take part in cultural life

• the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress

• the right of the individual to benefit from the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.

• the right to freedom from the interference of the state in scientific or creative pursuits.9

Several other aspects of culture are also protected in international human rights, for instance the right to marry and found a family, the right to express an opinion freely, the right to education, to receive and impart information, the right to rest and leisure, and the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.

Because culture affects all aspects of human life, cultural rights illustrate the indivisibility and interdependence of all rights in a more comprehensive fashion than do any other rights. … cultural rights are often an inextricable part of other rights.10

Human Rights Resource Centre of the University of Minnesota

Question: What other human rights are related to culture?

In relation to children, the CRC stipulates that the education of the child shall be directed to “... the development of the child’s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential”, and Article 31 refers to the right to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child. Sports and games are essential activities for the personal and social development, growth and well-being of children and young people.

In 1966, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) emphasised the importance of culture: “recognising that, in accordance with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the ideal of free human beings enjoying freedom from fear and want can only be achieved if conditions are created whereby everyone may enjoy his economic, social and cultural rights, as well as his civil and political rights”.

The UNESCO Principles on International Cultural Co-operation (1966) also state that the wide diffusion of culture and the education of humanity, liberty and peace are indispensable to the dignity of man. Article I states:

1. Each culture has a dignity and value, which must be respected and preserved.

2. Every people have the right and the duty to develop its culture.

3. In their rich variety and diversity, and in the reciprocal influences they exert on one another, all cultures form part of the common heritage belonging to all mankind.11

All cultures form part of the common heritage belonging to all mankind.

UNESCO

In 2007, the adoption of the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People12 was an impor-

tant step in clarifying the concept of culture within human rights law. It affirms that indigenous

peoples are equal to all other peoples, while recognising the right of all peoples to be different, to consider themselves different, and to be respected as such, and affirms also that all peoples contribute to the diversity and richness of civilisations and cultures, which constitute the common heritage of humankind.

Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People

Article 8

1. Indigenous peoples and individuals have the right not to be subjected to forced assimilation or destruction of their culture.

2. States shall provide effective mechanisms for prevention of, and redress for:

(a) Any action, which has the aim or effect of depriving them of their integrity as distinct peoples, or of their cultural values or ethnic identities;

Article 11

1. Indigenous peoples have the right to practise and revitalize their cultural traditions and customs. This includes the right to maintain, protect and develop the past, present and future manifestations of their cultures, such as archaeological and historical sites, artefacts, designs, ceremonies, technologies and visual and performing arts and literature.

Can cultural practices violate human rights?

The UNESCO Principles on International Cultural Co-operation states that each culture has a dignity and value, which must be respected and preserved. What does this principle mean in practice?

Practices such as bull fights, showing fanatical support for a football club, drinking warm beer, hunting whales or eating horse meat may be important practices to some but seem daft or even offensive to others. There are other practices that have more fundamental consequences for people’s rights and dignity, for instance, the use of capital punishment, customs about being sexually active (or not) before marriage, wearing religious symbols, or corporal punishment of children.

For it is often the way we look at other people that

imprisons them within their own narrowest allegiances.

Amin Maalouf14

Question: Should all cultural practices be respected?

The United Nations takes a clear stand on this issue: one right cannot be used to violate other rights, as stated the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

[…] cultural rights cannot be invoked or interpreted in such a way as to justify any act leading to the denial or violation of other human rights and fundamental freedoms. As such, claiming cultural relativism as an excuse to violate or deny human rights is an abuse of the right to culture.

There are legitimate, substantive limitations on cultural practices, even on well-entrenched traditions. For example, no culture today can legitimately claim a right to practise slavery.

Despite its practice in many cultures throughout history, slavery today cannot be considered legitimate, legal, or part of a cultural legacy entitled to protection in any way. To the contrary, all forms of slavery, including contemporary slavery-like practices, are a gross violation of human rights under international law.

Similarly, cultural rights do not justify torture, murder, genocide, discrimination on grounds of sex, race, language or religion, or violation of any of the other universal human rights and fundamental freedoms established in international law. Any attempts to justify such violations on the basis of culture have no validity under international law.13

Among the pitfalls of making unconsidered claims about cultural rights is that we may fall into the trap of labelling people, “putting them in a box” according to their culture, and consequently perpetuating stereotypes and prejudices. It is especially typical of representatives of a majority culture to consider all choices, actions or decisions of the member of a minority group as something related to their culture, while they consider their own actions, choices or decisions as not at all influenced by culture, but as being “objective”.

J’ai droit à l’égalité lorsque la différence cause mon infériorité ; j’ai droit à la différence lorsque l’égalité ignore les caractéristiques qui me définissent.

Boaventura Sousa Santos

Cultural diversity is a natural consequence of the combination of human dignity and human rights in their entirety. Human rights guarantee the freedom of thought, religion, belief, cultural expression, education, and so on. In the same way that the power of majorities cannot be used to suppress the human rights of minorities, the cultural rights of minorities cannot be used to justify violations of human rights, be they perpetrated by minorities themselves or by the majorities.

Respect for diversity ought to occur in a human rights framework and not be used as a reason for discrimination. Diversity is only possible in dignity; equality has to coexist with diversity.

Sports and human rights

Pierre de Coubertin – “father” of the modern Olympic Games – believed that sports events in general and international ones in particular were important tools for the promotion of human rights:

sports should have the explicit function to encourage active peace, international understanding in a spirit of mutual respect between people from different origins, ideologies and creeds.

No human rights declarations or covenants contain a specific mention of sport. Nonetheless, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) stated in its Olympic Charter that the “practice of sport is a human right. Every individual must have the possibility of practising sport, without discrimination of any kind and in the Olympic spirit”.15

Participation in sport can promote human rights through generating shared interests and values and teaching social skills that are necessary for democratic citizenship. Sport enhances social and cultural life by bringing together individuals and communities. Sports can help to overcome difference and encourages dialogue, and thereby helps to break down prejudice, stereotypes, cultural differences, ignorance, intolerance and discrimination.

Sport is often used as a first step to engage vulnerable and marginalised groups. Street football is used in many inner city areas as a way for youth workers to make contact with alienated young people. The Homeless World Cup is an international football tournament where teams are made up entirely of homeless people. The event has been held annually since 2003. On the official website of the organisation we can read that “… the research into the impact of the Copenhagen 2007 Homeless World Cup once again demonstrates significant change in the lives of the players - 71% of players came off drugs and alcohol, moving into jobs, homes,

training, education, repairing relationships all whilst continuing to play football”.16

Sports players as role models

The most important thing is not to win but to take part.

Motto of the Olympic Games

Sportsmen and sportswomen are often admired for their status, achievements, and sometimes for their inspiring journey to success. Many young people look up to them for their efforts to fight for social justice and human rights. For example, Lilian Thuram is the most capped player in the history of the French National football team and known for his fight against racism and defence of young people. Eric Cantona is also a famous former footballer. He came from a poor immigrant family and is now well known for acting, and his support for the homeless.

The UN relies on some prominent personalities from the world of art, music, film, literature and sport to draw attention to its activities and promote the mission of the organisation.

Examples include the following: footballer Leo Messi, Goodwill Ambassador for UNICEF; tennis star Maria Sharapova, Goodwill Ambassador for the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and singer Céline Dion, UNESCO Artist for Peace.17

Sport Without Borders18

Sport Without Borders is a non-profit organisation started by a group of athletes from a variety of sports. It is committed to defending the right to play and to participate in sports: every child, irrespective of socio-economic status or the context in which (s)he lives, must have the right to play and to participate in sport; it promotes education through sport working with at-risk populations and is thus contributing to the fight against inequality. Its motto is “Solidarity is primarily a collective sport”.

www.playthegame.org

Human rights violations related to sports

The use of performance enhancing drugs is probably the most well known abuse of human dignity and health. There are also controversial issues of hormone treatment and sex-testing of women athletes that have to do with respect, human dignity and the right to privacy. Sponsors can exploit sportsmen and women, and ambitious parents can exploit children who demonstrate precocious ability. Intensive training and pressure to compete can lead to sports injuries and be a risk to mental well-being.

Sporting opportunities are not always inclusive and there are often elements of discrimination against women, religious or cultural minorities or other groups in access to sports facilities, for instance, football classes offered only for boys at school. Commercial pressures and interests may lead to human rights abuses that undermine dignity and respect for others. For instance, some players accept bribes to commit “professional fouls” in soccer or to fix matches in cricket.

Some human rights abuses are associated with the globalisation of the sporting goods industry. For example, sportswear and equipment suppliers have been criticised for contracting with factories where child labour is used.

Question: Are all sports equally accessible to all young people?

The most common human rights challenge related to sport is equality and non-discrimination.

The effective exercise of equality in access to sport is faced with various economic, social and logistical barriers: existence of sport facilities, being able to access them and to afford them, being admitted to sports clubs and facilities, accessibility of the facilities, and so on. Despite the widely recognised integration role of sport, in most countries many young people are de facto deprived from access to sport.

Sport and politics

Sport has long been used as a peaceful means of political action against injustice. During the apartheid era, many countries refused to have sporting relations with South Africa, which made a significant contribution to political change in that country. In 1992, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was replaced by Denmark in the UEFA European Football Championship because of the state of war amongst republics in former Yugoslavia.

However, sport may also be misused for nationalistic or political purposes. For instance, at the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, eight Palestinian terrorists invaded the Israeli team headquarters to take hostages. Two of the sportsmen were killed in the brawl, and nine hostages were murdered after a failed rescue attempt by German police. The Olympic Games, in particular, have long been used as a forum for nations to make political statements. For example, the United States of America together with 65 other nations boycotted the Moscow games of 1980 because of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The Soviet Union and fifteen of its allies then boycotted the next games in Los Angeles in 1984 for security reasons and fears of political asylum being sought and given. More recently the choice of Beijing for the 2008 Olympic Games was criticised because of China’s lack of democracy and human rights abuses.

Sport and racism

Racism in sport can affect all sports and can manifest itself at several levels, in amateur sport and at institutional and international levels, as well as in the media. It can occur at local level particularly, but not exclusively, in the interaction (for real or imagined reasons of colour, religion, nationality or ethnic origin) between or against players, teams, coaches and spectators and also against referees.

The responsibility for combating racism in sport falls on everyone, including public authorities (law-makers, courts, the police, governmental bodies responsible for sport and local authorities), non-governmental organisations (professional and amateur national sports associations, clubs, local sports associations, supporters’ clubs, players’ organisations, anti-racist associations and so on) and individuals.

Mondiali Antirazzisti

This is an international football tournament and a big festival of anti-racism, held each year near Bologna, Italy. It is open to fan groups, anti-racist organisations, immigrant associations, youth groups, and everyone who enjoys fair-play football. The tournament is non-competitive and aims to bring people together. Besides the matches, many other activities are organised, such as discussions, workshops, film screenings, concerts and so on.

http://www.mondialiantirazzisti.org

Question: Should a suspected hooligan be banned from travelling to another country to attend a match? What about their right to freedom of movement?

Culture and young people

What is happening to our

young people?

They disrespect their elders, they disobey their parents.

They ignore the law. They riot in the streets inflamed with wild notions. Their morals are decaying. What is to become of them?

Plato, 4th century BC

We often generalise and speak about a particular country’s culture and overlook the fact that culture is pluralistic. Similarly, it is misleading to talk about youth culture as a homogeneous construct. In Europe, the social, economic changes that have taken place since World War II have led to a burgeoning of youth sub-cultures. Young people, with their own specific needs, knowledge, principles, practices, interests, behaviours and dreams, renew the culture in which they grow up and make it theirs, some by fully embracing it, others by refusing it.

Access to and participation in cultural activities can be a vector of cohesion and integration and promote active citizenship. Thus, it is important that young people have “access to culture”, whether as consumers, for instance of libraries, museums, operas or football matches, or as producers, for instance, of music and video films or active participants in dance or sports.

Question: Do all citizens in your country have equal access to participation in the cultural life of the society?

The European Youth Forum is the platform of European youth organisations.

www.youthforum.org

Access of young people to culture may be facilitated in various ways, for example through offering subsidised prices, season tickets, decreased subscription schemes, or free access for young people to museums, art galleries, operas, theatre performances and symphony orchestra concerts. Access is also encouraged through educational and leisure activities, for example subsidies to youth theatre groups and the provision of youth clubs, community centres, youth and culture centres.

The Revised European Charter on the Participation of Young People in Local and Regional Life recommends local and regional authorities to “support organised socio-cultural activities – run by youth associations and organisations, youth groups and community centres – which, together with the family and school or work, are one of the pillars of social cohesion in the municipality or region; these are an ideal channel for youth participation and the implementation of youth policies in the fields of sport, culture, crafts and trades, artistic and other forms of creation and expression, as well as in the field of social action”.

In the understanding of the charter, social and culturalparticipation are intertwined. Most youth organisations develop their activities in this spirit. They may or not have culture or sport as their first aim, but they exist and work to promote the well being of young people which cannot be realised without a social, cultural and sports component. Some youth organisations address directly forms of cultural participation and intercultural exchange (such as the European Federation for Intercultural Learning, Youth for Exchange and Understanding, or the Ecumenical Youth Council in Europe); others place a more direct focus on sports, such as the International Sports and Cultural Association or the European Sports Non-governmental Organisation. All of them, especially the multitude of big and small organisations active at local level, offer opportunities for young people to be actors in social and cultural life, and this means a lot more than to be consumers of cultural offers made by others.

The work of the Council of Europe

The European Youth Card is a card offering discounts on culture, travel, accommodation, shopping and services in many European countries for young people.

www.eyca.org

European Cultural Convention19

This Council of Europe Convention dates from 1954. “The purpose of this Convention is to develop mutual understanding among the peoples of Europe and reciprocal appreciation of their cultural diversity, to safeguard European culture, to promote national contributions to Europe’s common cultural heritage respecting the same fundamental values and to encourage in particular the study of the languages, history and civilisation of the Parties to the Convention. The Convention contributes to concerted action by encouraging cultural activities of European interest.”

We need to develop a political culture based on Human Rights.

Nelson Mandela

White Paper on Intercultural Dialogue

In 2008, the Council of Europe Ministers launched the Council of Europe White Paper on Intercultural Dialogue, “Living Together as Equals in Dignity”. In the Council of Europe, intercultural dialogue is seen as a means of promoting awareness, understanding, reconciliation and tolerance, as well as preventing conflicts and ensuring integration and the cohesion of society. The White Paper provides various orientations for the promotion of intercultural dialogue, mutual respect and understanding, based on the core values of the Organisation. The Ministers emphasised the importance of ensuring appropriate visibility of the White Paper, and called on the Council of Europe and its member states, as well as other relevant stakeholders, to give suitable follow-up to the White Paper’s recommendations.

The Anti-Doping Convention

The Anti-Doping Convention is the international legal reference instrument in the fight against doping. It was opened for signature in 1989 and so far 51 countries have ratified it. The Convention sets common standards and regulations requiring parties to adopt legislative, financial, technical, educational and other measures to combat doping in sports.

European Convention on Spectator Violence

The Convention aims to prevent and to control spectator violence and misbehaviour as well as to ensure the safety of spectators at sports events. The Convention has been ratified by 41 states. It concerns all sports in general, but football in particular. It commits states to taking practical measures to prevent and control violence. It also sets out measures for identifying and prosecuting offenders.

The Paralympic Games

The Paralympic Games are an athletic competition for people with disabilities, including amputees, people with impaired vision, paraplegics and people with cerebral palsy. The Paralympic Games originated in 1948 and since 1952 the Paralympics have been staged in Olympic years. The Winter Paralympics were first held in 1976. The first true parallel with the Olympic Games took place in 1988 in Seoul, South Korea, where the athletes had a Paralympic village and used Olympic sites for competition. The Paralympics are recognised and supported by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and governed by the International Paralympic Committee (IPC).

Towards a culture of human rights

While we all communicate in various ways and degrees in various cultures and “sub-cultures”, we are also, first and foremost, human beings and, in that sense, actors and players in the most universal culture, a human rights culture. This is a culture where humans know and respect one’s own rights as well as the rights of others, are responsible for one’s dignity and the dignity of others and act every day in ways coherent with the principles of human rights.

It is not a question of creating a new culture or a new ideology or philosophy, but of supporting every culture to integrate human rights principles into their laws, political systems and cultural practices. Maybe a good way to start is by seeing the world around you though the lens of human rights and acting consequently.23 This is because protecting and promoting human rights is not a specificity of any particular culture, religion or ethnicity: it is what should unite us all in our various cultural and identity affiliations.

Notes

1 “Generation of change, young people and culture”, Youth Supplement to UNFPA’s State of the World Population Report, 2008: www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/2008/swp_youth_08_eng.pdf

2 ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_334_fr.pdf

3 Aime Cesair, Martiniquen writer, speaking to the World Congress of Black Writers and Artists in Paris: www.wsu.edu/gened/learn-modules/top_culture/quotations-on-culture

4 The online etymology dictionary: www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=culture (traduction libre en français)

5 General comment No. 21 to art. 15, para. 1 (a), of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 2009

6 T-Kit on Training Essentials, Council of Europe and European Commission, 2002: www.youth.partnership-eu.coe.int/youth-partnership/publications/T-kits/6/Tkit_6_FR

7 European Sports Charter, Council of Europe, 1993

8 Human Rights Education Associates: www.hrea.org/index.php?base_id=157

9 www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/

10 Circle of Rights, Human Rights Resource Center, Section 5 Module 17: www1.umn.edu/humanrts/edumat/IHRIP/circle/modules/module17.htm

11 portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13147&URL_DO=DO_PRINTPAGE&URL_SECTION=201.html

12 www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

13 Ayton-Shenker Diana, “The Challenge of Human Rights”, United Nations Department of Public Information DPI/1627/HR 1995: www.un.org/rights/dpi1627e.htm

14 Amin Maalouf, In the name of Identity: Violence and the need to belong, New York: Arcade Publishing 2000.

15Olympic Charter, International Olympic Committee, 2011: www.olympic.org/Documents/olympic_charter_en.pdf

16 For more information, see: www.homelessworldcup.org/

17 See more extensive lists at www.un.org/sg/mop/gwa.shtml et http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=4049&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

18For more information, see: www.sportsansfrontieres.org

19 conventions.coe.int/Treaty/Commun/QueVoulezVous.asp?NT=018&CL=FRE&NT=018

20 www.coe.int/t/dg4/intercultural/Source/Pub_White_Paper/White%20Paper_final_revised_FR.pdf

21 http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/Commun/QueVoulezVous.asp?CL=FRE&NT=135

22 http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/Commun/QueVoulezVous.asp?CL=FRE&NT=120

23 Interesting discussion around this issue in Human Rights Education Associated Forum: www.hrea.org/lists/hr-education/markup/msg01188.html

Key Date

- 21 FebruaryInternational Mother Language Day

- 21 MarchWorld Poetry Day

- 23 AprilWorld Book and Copyright Day

- 3 MayWorld Press Freedom Day

- 21 MayWorld Day for Cultural Diversity for Dialogue and Development

- 28 MayEuropean Neighbours Day

- 9 AugustInternational Day of Indigenous People

- 12 AugustInternational Youth Day

- 1 OctoberInternational Day of Older Persons

- 1 OctoberInternational Music Day

- 25 OctoberInternational Artists Day

- 11 NovemberInternational Day of Science and Peace

- 21 NovemberWorld Television Day

Culture is everything. Culture is the way we dress, the way we carry our heads, the way we walk, the way we tie our ties. It is not only the fact of writing books or building houses.

Aimé Cesaire3