Peace and Violence

Violence: concepts and examples

What is violence?

Violence is a complex concept. Violence is often understood as the use or threat of force that can result in injury, harm, deprivation or even death. It may be physical, verbal or psychological. The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines violence as "intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation".1 This definition emphasises intentionality, and broadens the concept to include acts resulting from power relationships.

An expanded understanding of violence includes not only direct "behavioural" violence, but also structural violence, which is often unconscious. Structural violence results from unjust and inequitable social and economic structures and manifesting itself in for example, poverty and deprivation of all kinds.

Forms of violence can be categorised in many ways. One such classification includes:

- direct violence, e.g. physical or behavioural violence such as war, bullying, domestic violence, exclusion or torture

- structural violence, e.g. poverty and deprivation of basic resources and access to rights; oppressive systems that enslave, intimidate, and abuse dissenters as well as the poor, powerless and marginalised

- cultural violence, e.g. the devaluing and destruction of particular human identities and ways of life, the violence of sexism, ethnocentrism, racism and colonial ideologies, and other forms of moral exclusion that rationalise aggression, domination, inequity, and oppression.

Question: Are direct, structural and/or cultural violence present in your community? How?

Today's human rights violations are the causes of tomorrow's conflicts.

Mary Robinson

Violence in the world

Each year, more than 1.6 million people worldwide lose their lives to violence. For every person who dies as a result of violence, many more are injured and suffer from a range of physical, sexual, reproductive and mental health problems. Violence places a massive burden on national economies in health care, law enforcement and lost productivity.

World Health Organisation2

Structural and cultural forms of violence are often deeply impregnated in societies to the point of being perceived as inherent. This type of violence lasts longer, thus eventually having similar consequences as direct violence, or, in some cases, even leading to the oppressed using direct violence as a response. Lower education opportunities in disadvantaged neighbourhoods, limited access to leisure for foreigners, harmful working conditions in certain fields of work, and so on, are acts of structural and cultural violence which have a direct influence on people's access to their rights. Yet these forms of violence are rarely recognised as violations of human rights.

What follows are some examples about different forms of violence worldwide. These are not the only ones. More information about the effects of armed conflicts can be found in War and Terrorism and in various other sections of this manual.

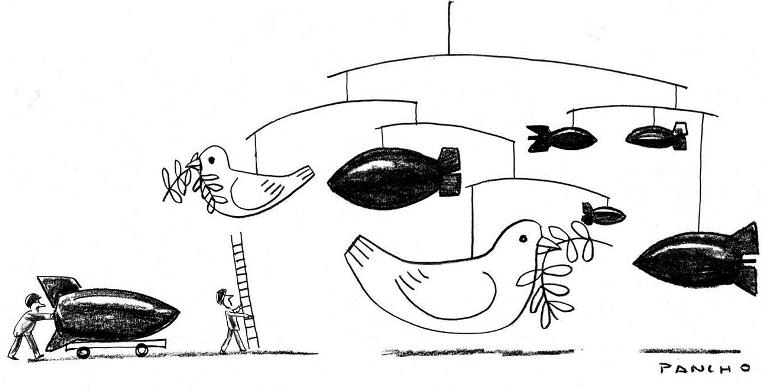

Military spending, arms trade and violence

The production and trade in arms and weapons is undoubtedly one of the greatest threats to peace, not least because of the economic, financial and social dimensions of arms production. The production and export of arms is often encouraged on economic grounds with little con- sideration to the impact on peace and security. World military spending is steadily increasing; in 2014 the world spent an estimated €1776 billion on the military. The database of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute3 shows in 2014 the USA (€610 billion) as the biggest military spender, followed by China (€216 billion) and then three European countries, Russia ($84 billion) the United Kingdom ($60 billion) and France (€62 billion). Europe as a whole spent $386 billion.

Data from the Overseas Development Institute (www.odi.org ) shows that we could deliver free primary and secondary education in all the poor countries around the world for $32 billion per year, this is less than a single week's global military spending.

Question: How much does your country of residence spend on arms production and purchases annually?

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates that at least 740,000 women, men, young people and children are killed each year by armed violence; most of those affected live in poverty. The majority of armed killings occur outside of wars, although armed conflicts continue to generate a high number of deaths. Moreover, a huge number of people are injured by armed violence and face long-term suffering because of it. According to Amnesty International, about 60% of human rights violations documented by the organisation have involved the use of small arms and light weapons.4

Controlling Arms Trade

Control Arms is a global civil society alliance campaigning for an international legally-binding treaty that will stop the transfer of arms and ammunition. The campaign emphasises that domestic regulations have failed to adapt to increasing globalisation of the arms trade since different parts of weapons are produced in different places and transferred to other countries to be assembled. Control Arms is calling for a "bulletproof" Arms Trade Treaty that would hold governments accountable for illegal arms transfers.

www.controlarms.org

Bullying

A form of inter-personal violence, bullying is one of the forms of violence that affects young people and is often not considered as a form of violence. Bullying refers to aggressive behaviour which is repeated and intends to hurt someone. It can take the form of physical, psychological or verbal aggression. It can take place in any situation where human beings interact, be it at school, at the workplace or any other social place. Bullying can be direct, confronting a person face-to-face, or indirect by spreading rumours or harming someone over the Internet, for example. Although it is difficult to have clear statistics, research shows that bullying is an increasing problem. Victims often do not dare to speak out, and it is therefore extremely difficult to identify and support victims of bullying.

Is corporal punishment legitimate?

Corporal punishment is the most widespread form of violence against children and is a violation of their human rights. In the past, some argued that smacking was a harmless form of punishment which enabled parents to educate their children, whereas others considered it a violent form of physical punishment. The Council of Europe campaign Raise Your Hand Against Smacking provoked strong debates in Member States, and took a human rights stand against this practice.

Gender-based violence

More information about gender and gender-based violence, can be found in the section on Gender, in chapter 5, and in the manual Gender Matters, www.coe.int/compass

While male-dominated societies often justify small arms possession through the alleged need to protect vulnerable women, women actually face greater danger of violence when their families and communities are armed.

Barbara Frey6

Gender-based violence is one of the most frequent forms of structural and cultural violence. It is present in every society and its consequences affect virtually all human beings. According to the UNFPA, gender-based violence "both reflects and reinforces inequities between men and women and compromises the health, dignity, security and autonomy of its victims. It encompasses a wide range of human rights violations, including sexual abuse of children, rape, domestic violence, sexual assault and harassment, trafficking of women and girls and several harmful traditional practices. Any one of these abuses can leave deep psychological scars, damage the health of women and girls in general, including their reproductive and sexual health, and in some instances, results in death"5.

Gender-based violence does not have to be physical. In fact, young people suffer much verbal violence, especially targeted at LGBT (young) people and girls.

Everyone has the right, individually and in association with others, to promote and to strive for the protection and realization of human rights and fundamental freedoms at the national and international levels.

Article 1 of the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders

In situations of conflict, women become particularly vulnerable and new forms of violence against women emerge. These can range from mass rape to forced sexual assaults, forced pregnancy, or sexual slavery. The polarisation of gender roles during armed conflicts is increased, women thus being seen as objects of war and territories to be conquered.

Violence Against Human Rights Defenders

Useful information for human rights defenders:

www.frontlinedefenders.org/

www.amnesty.org/en/human-rights-defenders

www.ohchr.org

http://www.civilrightsdefenders.org

Investigating, reporting human rights violations and educating people about human rights and campaigning for justice can be dangerous work. Human rights defenders are people who individually, or with others, promote and protect human rights through peaceful and non-violent means. Because of their work, human rights defenders can be subjected to different types of violence, including beatings, arbitrary arrest or execution, torture, death threats, harassment and defamation, or restrictions on their freedom of expression, and association.

In 2000, the United Nations established a Special Rapporteur whose main mission is to support implementation of the 1998 Declaration on human rights defenders. The "protection" of human rights defenders includes protecting the defenders themselves and the right to defend human rights. The Special Rapporteur seeks, receives, examines and responds to information on the situation of human rights defenders, promotes the effective implementation of the Declaration and recommends strategies to protect human rights defenders.7

Question: How free and safe is it to report or denounce human rights abuse and violations in your country?

If you look at them [conflicts] and remove the superficial levels of religion and politics, quite often it is a question of trying to access resources, trying to control those resources, and trying to decide how those resources will be shared.

Wangari Maathai

The fight for resources

The possession of or control over natural resources such as water, arable land, mineral oil, metals, natural gas, and so on, have often fuelled violent conflicts throughout history. The depletion of certain resources and the shortage of others, such as water or arable land, is expected to become more widespread due to growth of consumption and climate change. This may create more regional or international tensions, potentially leading to violent conflicts.

Question: How is your country part of the competition for scarce resources?

Peace, human security and human rights

War and violence inevitably result in the denial of human rights. Building a culture of human rights is a pre-condition to achieving a state of peace. Sustainable, lasting peace and security can only be attained when all human rights are fulfilled. Building and maintaining a culture of peace is a shared challenge for humankind.

What is peace?

A culture of peace will be achieved when citizens of the world understand global problems, have the skills to resolve conflicts and struggle for justice non-violently, live by international standards of human rights and equity, appreciate cultural diversity, and respect the Earth and each other. Such learning can only be achieved with systematic education for peace.

Global Campaign for Peace Education of the Hague Appeal for Peace

FIAN is an international human rights organisation that has advocated for the realisation of the right to food.

www.fian.org

The above campaign statement offers a broader understanding of peace: peace means not only the lack of violent conflicts, but also the presence of justice and equity, as well as respect for human rights and for the Earth.

Johan Galtung, a recognised Norwegian scholar and researcher, defined two aspects of peace. Negative peace means that there is no war, no violent conflict between states or within states. Positive peace means no war or violent conflict combined with a situation where there is equity, justice and development.

The absence of war by itself does not guarantee that people do not suffer psychological violence, repression, injustice and a lack of access to their rights. Therefore, peace cannot be defined only by negative peace.

The concept of peace also has an important cultural dimension. Traditionally, for many people in the "western world", peace is generally understood to be an outside condition., while in other cultures, peace also has to do with inner peace (peace in our minds or hearts). In the Maya tradition, for example, peace refers to the concept of welfare; it is linked to the idea of a perfect balance between the different areas of our lives. Peace, therefore, is to be seen as both internal and external processes which affect us.

Human security

A concept closely related to peace and violence is human security, which recognises the interrelation between violence and deprivation of all kinds. It concerns the protection of individuals and communities from both the direct threat of physical violence and the indirect threats that result from poverty and other forms of social, economic or political inequalities, as well as natural disasters and disease. A country may not be under threat of external attack or internal conflict but still be insecure if, for example, it lacks the capacity to maintain the rule of law, if large populations are displaced by famine or decimated by disease or if its people lack the basic necessities of survival and access to their human rights.

Human security furthers human rights because it addresses situations that gravely threaten human rights and supports the development of systems that give people the building blocks of survival, dignity and essential freedoms: freedom from want, freedom from fear and freedom to take action on one's own behalf. It uses two general strategies to accomplish this: protection and empowerment. Protection shields people from direct dangers, but also seeks to develop norms, processes and institutions that maintain security. Empowerment enables people to develop their potential and become full participants in decision making. Protection and empowerment are mutually reinforcing, and both are required.

Question: How does insecurity affect the young people with whom you work?

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the UN in 2015 recognise the important role of security for development. SDG 16, sometimes shortened to “Peace and Justice” is to “promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels”. There are 10 targets, for instance 16.1 to reduce all forms of violence, 16.2 end abuse and all forms of violence against and torture of children. The full list of targets is in the further information section of the activity, “How much do we need?”.

The linkages between SDG 16 and human rights are:

- Right to life, liberty and security of the person [UDHR art. 3; ICCPR arts. 6(1), 9(1);

- ICPED art. 1] including freedom from torture [UDHR art. 5; ICCPR art. 7; CAT art. 2; CRC art. 37(a)]

- Protection of children from all forms of violence, abuse or exploitation [CRC arts. 19, 37(a)), including trafficking (CRC arts. 34-36; CRC–OP1)]

- Right to access to justice and due process [UDHR arts. 8, 10; ICCPR arts. 2(3), 14-15; CEDAW art. 2(c)]

- Right to legal personality [UDHR art. 6; ICCPR art. 16; CRPD art. 12]

- Right to participate in public affairs [UDHR art. 21; ICCPR art. 25]

- Right to access to information [UDHR art. 19; ICCPR art. 19(1)] (www.ohchr.org)

Peace as a human right

Peace is a way of living together so that all members of society can accomplish their human rights. It is as an essential element to the realisation of all human rights. Peace is a product of human rights: the more a society promotes, protects and fulfils the human rights of its people, the greater its chances for curbing violence and resolving conflicts peacefully.

However, peace is also increasingly being recognised as a human right itself, as an emerging human right or part of the so-called solidarity rights.

Non-violence is the supreme law of life.

Indian proverb

All peoples shall have the right to national and international peace and security.

African Charter on Human and People's Rights, Article 23

The connection between international human rights and the right to peace is very strong, notably because the absence of peace leads to so many violations of human rights.

The UDHR recognises, for example, the right to security and freedom (Article 3); prohibits torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Article 5), and calls for an international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in the declaration can be fully realised (Article 28). The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights prohibits propaganda for war as well as "advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence" (Article 20).

The right to peace is also codified in some regional documents such as the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights and the Asian Human Rights Charter. The creation of the Council of Europe was itself based on the conviction that "the pursuit of peace based upon justice and international co-operation is vital for the preservation of human society and civilisation".

The right to peace in UN Human Rights Council

"The Human Rights Council …

1. Reaffirms that the peoples of our planet have a sacred right to peace;

2. Also reaffirms that the preservation of the right of peoples to peace and the promotion of its implementation constitute a fundamental obliga-

tion of all States;

3. Stresses the importance of peace for the promotion and protection of all human rights for all;

4. Also stresses that the deep fault line that divides human society between the rich and the poor and the ever-increasing gap between the de-

veloped world and the developing world pose a major threat to global prosperity, peace, human rights, security and stability;

5. Further stresses that peace and security, development and human rights are the pillars of the United Nations system and the foundations for

collective security and well-being; …"11

The opposite of violence isn't non-violence, it's power. When one has moral power, power of conviction, the power to do good, one doesn't need violence.9

Nelsa Libertad Curbelo10

Human security is a child who did not die, a disease that did not spread, a job that was not cut, an ethnic tension that did not explode in violence, a dissident who was not silenced. Human security is not a concern with weapons – it is a concern with human life and dignity.

Human Development Report, 1994

The Santiago Declaration on the Human Right to Peace, adopted in 2010 by The International Congress on the Human Right to Peace, is one of the most elaborate documents on peace as a human right. The declaration recognises individuals, groups, peoples and all humankind as holders of the "inalienable right to a just, sustainable and lasting peace" (Art. 1) and "States, individually, jointly or as part of multilateral organisations", as the principal duty holders of the human right to peace". The declaration also calls for the right to education "on and for peace and all other human rights" as a component of the right to peace because "education and socialization for peace is a condition sine qua non for unlearning war and building identities disentangled from violence". The right to human security and the right to live in a safe and healthy environment, "including freedom from fear and from want" are also put forward as elements of "positive peace". Other dimensions of the right to peace are the right to disobedience and conscientious objection, the right to resist and oppose oppression and the right to disarmament.

The declaration also devotes a specific article to the rights of victims, including their right to seek justice and a breakdown of the obligations entailed in the human right to peace.

Question: In practice, what does the human right to peace mean for you?

Legitimate (state) violence

Not all violence is illegal or illegitimate. Violent acts are sometimes necessary in order to protect the human rights of other people. I may have to use violence for self-defence; I expect a policeman to use, in extreme cases, some kind of violence to protect me or my family from violence from other people. My human right to security implies that the state and its agents protect me from violence. A human rights framework implies that violent actions by state or public agents is justified (and sometimes required), provided that it is organised and enacted within a human rights framework, including respect for the rights of the victim.

All persons have a right to peace so that they can fully develop all their capacities, physical, intellectual, moral and spiritual, without being the target of any kind of violence.

Asian Human Rights Charter, 1998, paragraph 4.1

This raises questions about the primacy of some human rights over others: the right to life is a clear human right, and still in many cases, human beings are being punished violently or killed, as a consequence of their acts.

Examples from throughout history illustrate how civil movements have brought about change and better access to people's human rights. However, peaceful movements are often suppressed by violent police or army action. Repressing people's right to freedom of expression and association. The "Arab Spring" movements initiated in 2011 showed how youth in Tunisia, Egypt and other Arab countries gathered and peacefully reclaimed their human rights, but were violently attacked and put into detention by state armed forces, many losing their lives.

Question: When is armed intervention by policy justified?

Starvation is the characteristic of some people not having enough to eat. It is not the characteristic of there not being enough to eat.

Amartya Sen

From a human rights perspective, the deprivation of the liberty of a person as a consequence of a criminal offence does not take away their inherent humanity. This is why the measures taken by the state against people who have acted violently against others must not be arbitrary, must respect their inherent dignity, and must protect these persons against torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. One of the aims of detention is the social rehabilitation of prisoners.

I object to violence because when it appears to do good, the good is only temporary; the evil it does is permanent.

Ghandi

The rule of law and protection of human rights and freedoms are crucial safeguards for an effective and just criminal justice system. Yet, while protecting the innocent12, custody and imprisonment are often also, unfortunately, the places where human rights violations appear.

According to human rights standards, in particular the Convention on the Rights of the Child, specific rehabilitation mechanisms must be put in place for young offenders, such as "laws, procedures, authorities and institutions specifically applicable to children alleged as, accused of, or recognized as having infringed the penal law" (Art. 40). This, however, is not always the case. According to Penal Reform International, the way authorities deal with young offenders can often lead to long-term physical and psychological ill-health. For example, exposure to violent behaviour in detention and separation from families and community may undermine the idea of rehabilitation and push them further into criminal activities. Based on the UNICEF estimates, today there are more than one million children in detention worldwide.

Question: Can imprisonment be an effective way to rehabilitate and educate children and young people who have committed a criminal offence?

Death penalty

The death penalty is forbidden by the European Convention on Human Rights as well as in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Protocol 1). Outlawing the death penalty does not justify human rights violations. It is also based on the belief that violence cannot be fought with more violence. The outlawing of the death penalty is also a statement about the infallibility of justice: history shows that judicial mistakes are always possible and that there is the risk that the wrong person may be executed. However, the outlawing of the death penalty is also a testament to the belief of the right to life and dignity - and to a fair trial.

Penal Reform International is an international non-governmental organisation working on penal and criminal justice reform worldwide.

www.penalreform.org

In 2011, 1,923 people in 63 countries were known to have been sentenced to death and 676 executions were known to have been carried out in 20 countries. However, the 676 figure does not include the perhaps thousands of people that Amnesty International estimates have been executed in China.13

Belarus is the only country in Europe that in 2012 still carried out executions. According to Amnesty International, prisoners on death row in Belarus are told that they will be executed only minutes before the sentence is carried out. They are executed by a shot to the back of the head. The family members are informed only after execution, and the place of burial is kept in secret.

Young people and a culture of peace

Conflict transformation, reconciliation, peace education, and remembrance are part of the actions that carry the hope for a life free from violence and for a culture of peace. We have to learn from the past and make efforts to avoid the reoccurrence of terrible events against humanity which previous generations lived through. There are still local wars and armed conflicts in some places of the world. It is comforting to know that we are not defenceless and that we have tools to eliminate violence. Young people play an important role in this change.

Only societies based on democracy, the rule of law and human rights can provide sustainable long-term stability and peace.

Thorbjørn Jagland, Secretary General of the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe works to promote social justice, and to avoid the escalation of violent conflicts and prevent wars and terrorist activities. The organisation encourages political leaders and civil society to build and nourish a culture of peace instead of a culture of violence and it raises awareness of the cost of violence, the perspectives of a peaceful future, the importance of democracy and democratic skills, as well as promoting humanism, human dignity, freedom and solidarity.

The Council of Europe's youth sector has over 40 years of experience in working on intercultural learning, conflict transformation and human rights education.

The adoption by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe of the White Paper on Intercultural Dialogue "Living Together as Equals in Dignity", confirmed the political relevance of these approaches, and emphasised the need for dialogue between cultures for the development and safeguarding of peaceful societies.

Meet your own prejudice! Instead of talking about it, simply meet it.

The Living Library Organiser's Guide14

The 7th Conference of European Ministers responsible for Youth (Budapest, 2005) was devoted to youth policy responses to violence. In the final declaration, the ministers agreed, amongst others, on the importance of taking stock of all forms of violence and of their impact on people, on the need to develop violence-prevention strategies and to recognise young people as actors in violence prevention, "whilst raising their sense of responsibility and actively promoting their participation and co-operation" in this domain. The declaration also recognises human rights education as containing an essential dimension of violence prevention.

The ministerial conference was the culmination of a project against violence in daily life which resulted in various educational instruments and initiatives to prevent and address violence, such as the manual for Living Library organisers.

As peace ambassadors we should become the eyes and ears of the Coun-cil of Europe in our countries and in Europe.

Zlata Kharitonova, participant in Youth Peace Ambassadors

The youth sector of the Council of Europe has also initiated and supported youth-led projects addressing conflict and promoting peace education. The Youth Peace Camp has been running since 2004, and brings together young people from different conflicting areas to engage in dialogue on the understanding that they share common values and experiences, often very painful ones. The programme helps youth leaders to recognise and address prejudice, combating aggressive and exclusive forms of nationalism, and implementing intercultural learning and human rights education. For some of the participants this is the first time in their lives that they have talked face-to-face with young people from "the other side". The camp is now held annually at the European Youth Centre and occasionally in member states.

Multiplying peace education

After the Youth Peace Camp 2011, six Israeli and Palestinian participants decided to keep meeting on the cease fire or so-called "green line". Every month other young people from both sides join the afternoon meeting, which includes discussions, sharing personal stories and having fun. As a joint group they engage in community work on both sides of the line, each time in a different community on a different side, always in a community affected somehow by the ongoing conflict.

The Youth Peace Ambassadors project, initiated in 2011, engages youth leaders in specific grassroots level peace education projects with young people, aiming at transforming conflict situations in their realities. The project is built on a network of specifically trained young people who strengthen the presence and promote the values of the Council of Europe in conflict-affected areas and communities.

Undoing Hate

In the last two years, the streets of Prijepolje, a multicultural town in Serbia, became surrounded by "wrong" graffiti, filled with hate speech towards foreigners and people with different religions (Muslim and Orthodox). Most of the graffiti is written by boys from 2 different hooligan groups.

My project brings together 10 boys, aged 14 – 18, from both a hooligan group and ethnic/religious minorities, who will redecorate the town by using graffiti to undo the hate graffiti which was put up in various places. While doing so, a peace-building documentary will be filmed. This project should help to create a strong basis for peace building, mutual understanding and tolerance.

Edo Sadikovic, JUMP organisation, Serbia (Youth Peace Ambassador's project)

Networks for peace

The following are some examples to consider the variety, seriousness and creativity of peace builders and human rights defenders.

Combatants for Peace – is a movement which was started jointly by Palestinians and Israelis who have taken an active part in the cycle of violence and now fight for peace.

Search for Common Ground implements conflict-transformation programmes.

Responding to Conflict provides training for conflict transformation. Inspiring examples of and study notes for conducting training can be found on their website.

The Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict is a global network seeking a new international consensus on moving from reaction to prevention of violent conflict.

The United Network of Young Peacebuilders is a network of youth-led organisations working towards establishing peaceful societies.

Endnotes

1 World report on violence and health, WHO 2002, Geneva p 5: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2002/9241545615.pdf

2 www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/en/

3 Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI): www.sipri.se

4 http://controlarms.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/killer_facts_en.pdf

5 www.unfpa.org/gender/violence.htm

6 Progress report of Barbara Frey, UN Special Rapporteur, "Prevention of human rights violations committed with small arms and light weapons", UN Doc. E/CN.4/Sub.2/2004/37, 21 June 2004, para 50

7 Source: www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/SRHRDefenders/

8 Evans, A., Resource scarcity, fair shares and development, WWF / Oxfam, Discussion paper, 2011

9 From the film Barrio De Paz

10 Nelsa Libertad Curbelo is a former nun and street gang mediator in Ecuador

11 UN General Asembly, 15 July 2011, Document A/HRC/RES/1/7/16 of the Human Rights Council

12 Based on the UK criminal Justice systems aims, see: http://ybtj.justice.gov.uk/

13 Amnesty International death penalty statistics

14 Don't judge a book by its cover – the Living Library Organiser's Guide, Abergel R. et al, Council of Europe Publishing, 2005

Key Date

- 12 FebruaryRed Hand Day

- 21 MarchInternational Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

- 15 MayInternational Day of Conscientious Objection

- 29 MayInternational Day of United Nations Peacekeepers

- 4 JuneInternational Day of Innocent Children Victims of Aggression

- 26 JuneUnited Nations International Day in Support of Victims of Torture

- 6 AugustHiroshima Day

- 21 SeptemberInternational Day of Peace

- 2 OctoberInternational Day of Non-Violence

- 10 OctoberWorld Day Against the Death Penalty

- 24-30 OctoberDisarmament Week

- 9 NovemberInternational Day Against Fascism and Antisemitism

- 11 NovemberInternational Day of Science and Peace

- 25 NovemberInternational Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women

- 2 DecemberInternational Day for the Abolition of Slavery

8 million light weapons are produced each year.

2 bullets are produced each year for every person on the planet.

2 out of 3 people killed by armed violence die in countries "at peace".

10 people are injured for every person killed by armed violence.

Estimates from www.controlarms.org